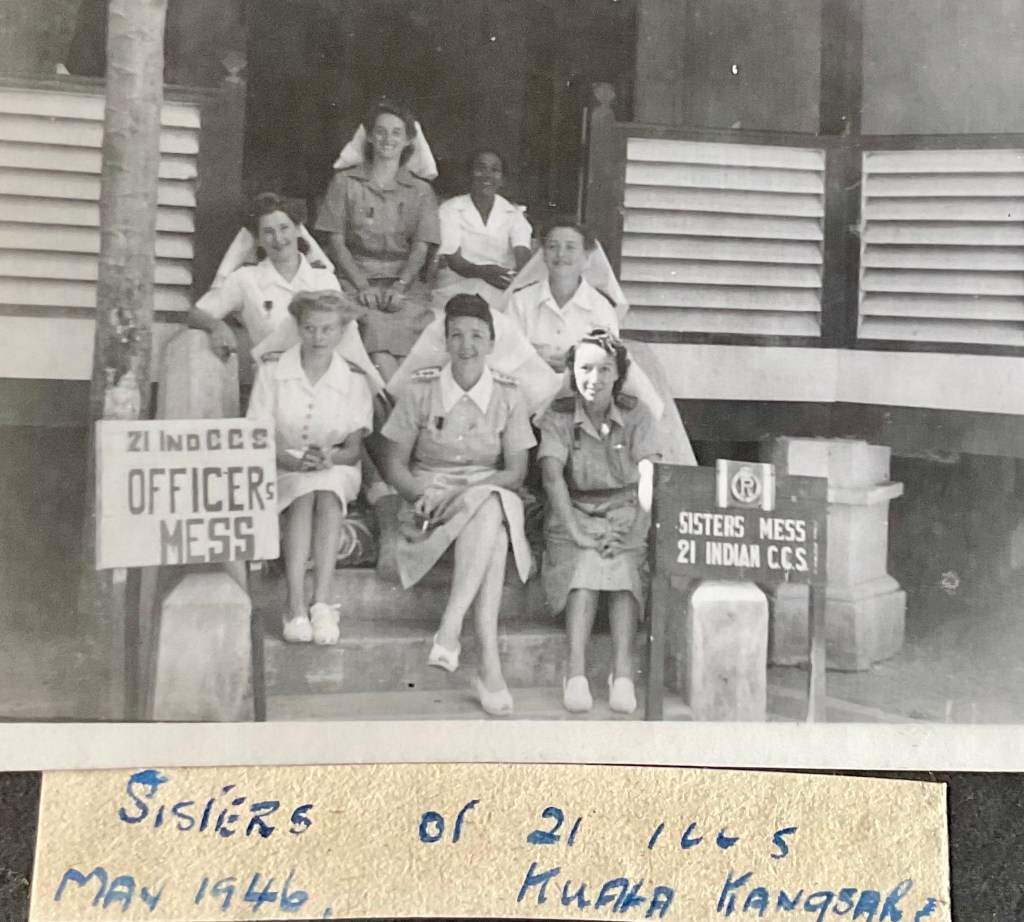

My aunt, Eileen Carlotta Smith (centre of photo taken in India) was born in the penultimate year of the First World War. She went on to train as a nurse, working from 1935 to the early years of the war at the former Blackpool, Devonshire Road Infectious diseases – mainly TB- hospital. From 1942 onwards she served overseas, firstly in India and then in Singapore and ‘Malaya’ nursing former POW’s. Throughout her working and personal life she was fastidious about ventilation and infection control and would have been a great advocate during the current pandemic. This is an edited version of what appears in my family history which is under production.

Early Life and Pre War Years

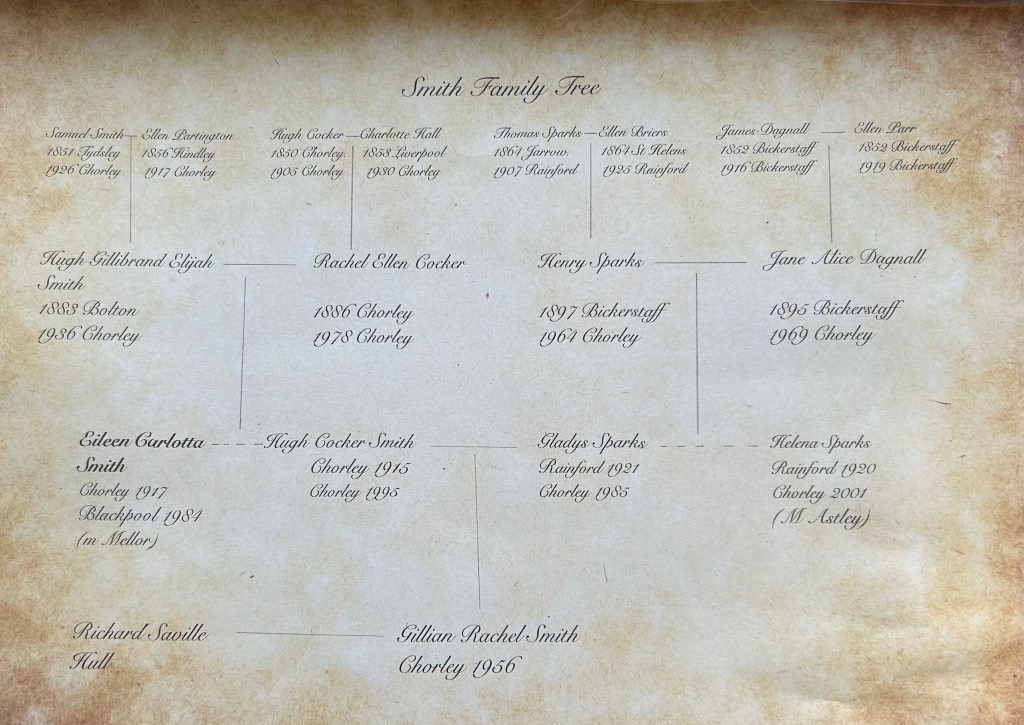

Rachel and Hugh Gillibrand Elijah Smith’s second child and Hugh Cocker Smith’s only sister (and hence first aunt to Gillian), Eileen Carlotta, was born in Water St, Chorley, Lancashire on 28 October 1917.

As far as we know she attended Hollingshead Street School Chorley until the age of about 14. We know that the family moved from Water Street, possibly via Commercial Road Chorley, to 1 Letchworth Drive in about 1930 when Eileen would have been about 13.

Eileen was training as a nurse at Blackpool at the time of her father’s (Hugh Gillibrand Elijah Smith) illness in September 1936, and was present at his death at 1 Letchworth Drive, Chorley.

The national nurses register reveals that Eileen undertook her training at the old Blackpool Hospital for infectious diseases and qualified as a nurse in October 1938. It is not clear why she choose to train at a relatively small specialist hospital rather than a general infirmary. It is true that many of the ancestors of Eileen’s mother (nee Cocker) who worked in the cotton mills died from TB and this may have been a key driver of her decision, but we don’t know.

In common with many hospitals of this nature (formerly called sanatoriums) patients were in the main suffering from tuberculosis (TB). This was an extremely dangerous disease and, in the absence of antibiotics the main cure was rest. Ventilation and fresh air were of obvious importance both to prevent the spread of the disease and to aid recovery and this is why so many of the former sanatoriums were located at the seaside.

I can well understand how Eileen gained a very good understanding of the importance of ventilation as was evident in her behaviours and attitudes throughout her life.

War Years

The nurses register reveals that Eileen moved to Blackburn Royal Infirmary in about 1940. Eileen joined the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) at some point in 1942 when she would have been 24/25. This was a highly selective elite corps and its members were entitled to equivalent rank with officers. The following account chimes with other sources that I have read:

To be accepted a recruit had to ‘fit in’. This meant not merely being a fully qualified nurse with up to four years training, but also a girl from a respectable middle-class family. She had to be British, preferably English, have a good education, speak well and know how to behave.

Once a nurse was accepted she would be sent to a mobilising unit …the purpose was two fold: to train recruits physically and professionally for what lay ahead and secondly to create a mobile hospital unit that would remain together, in different locations, for the duration of the war.

Sisters in Arms, Nicola Tyrer 2008

Although Eileen left school at 14, we assume that her general brightness, the fact that her brother (my father) was serving in the Royal Army Medical Corps as a pharmacist at the time, along with her training in infectious diseases would have carried her through the interview with a senior matron and counterbalanced any perceived shortcomings in her background or the fact that she was not from the Home Counties.

All of the sources I have read refer to the QAIMNS uniform which was required to be tailor made at Harrods and although there was a grant available it only covered half of the cost. We assume that one of the childless sisters of her late father whom she had always been close to – ‘Auntie Betty’ – would have been in a position to help with the costs. QAIMNS were also required to purchase a tin trunk as follows, which I think I may have seen and may have been left in the loft of Letchworth Drive, Chorley:

‘In the meantime, I was to purchase a black tin trunk and to have my name, rank, serial number and QAIMNS/R painted on in large white letters on the lid. I learned later that tin survived the tropical rain, heat, humidity and dust far better than leather. Leather tended to go mouldy, and all one’s clothes smelled awful.’

Recollection on the Imperial War Museum website

Eileen was sent to India in late 1942 or early 1943. It was common knowledge within the family that she went abroad without telling her mother that she was going because she did not want a huge fuss when she departed from Chorley railway station. Indeed, my grandmother was fond of telling us that the first she knew about it was when she received a postcard from what was then called Bombay informing her that Eileen had arrived!

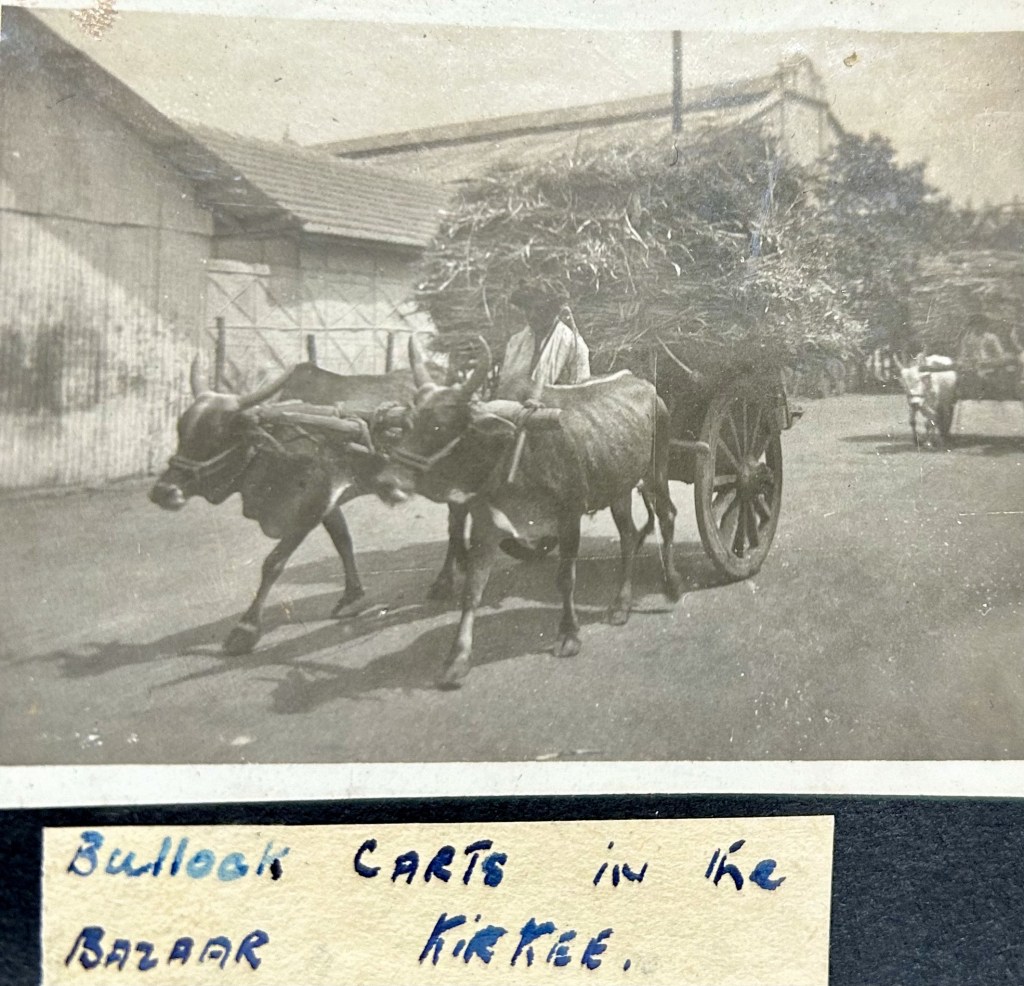

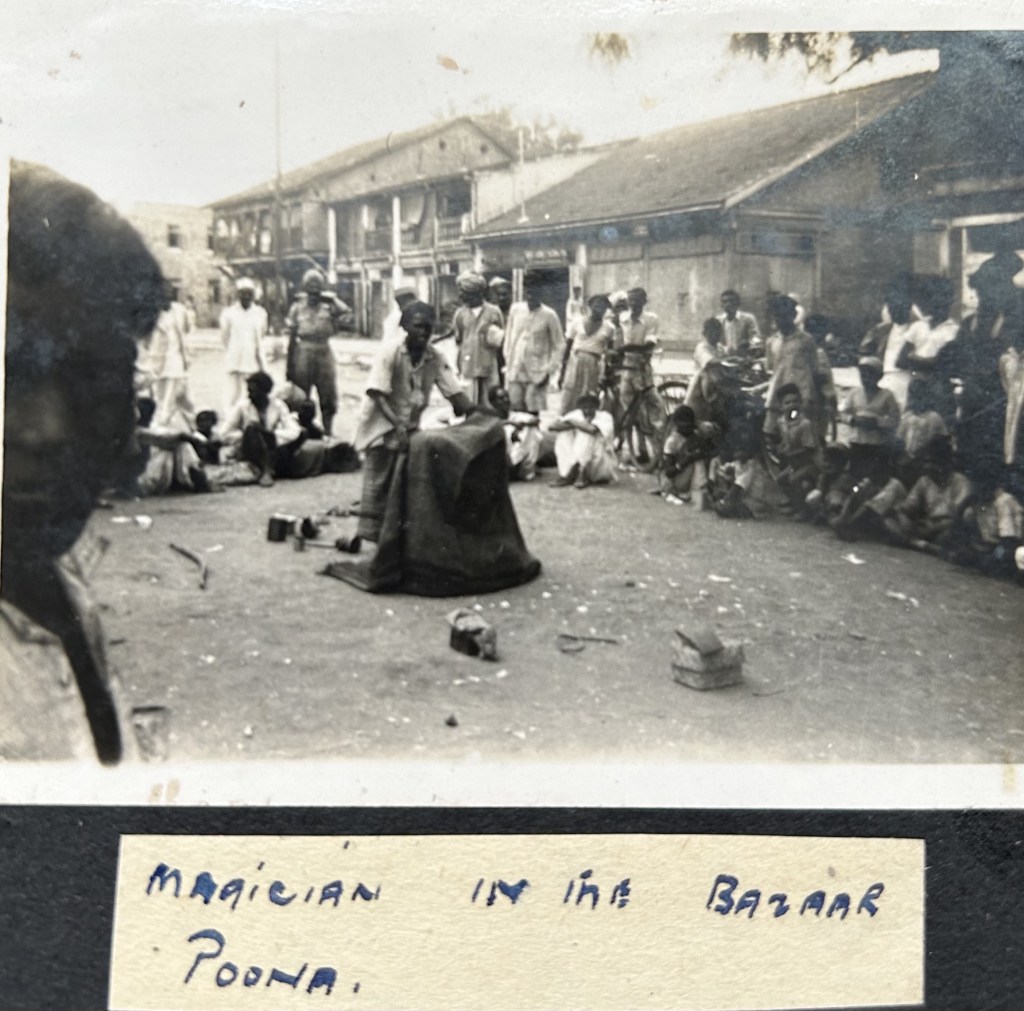

India was part of the British Empire and was drawn into World War 2 in 1939. The Japanese invasion of Burma in late 1941 brought the war ever closer to India, and at various points there was the threat that the Japanese would try to invade India.

Many of the casualties from the Burma Campaign who escaped capture were sent to India for treatment and the allied military presence in India increased considerably. From subsequent photographs we think Eileen may have been involved in training local nurses to form part of the unit which would eventually be shipped to Singapore.

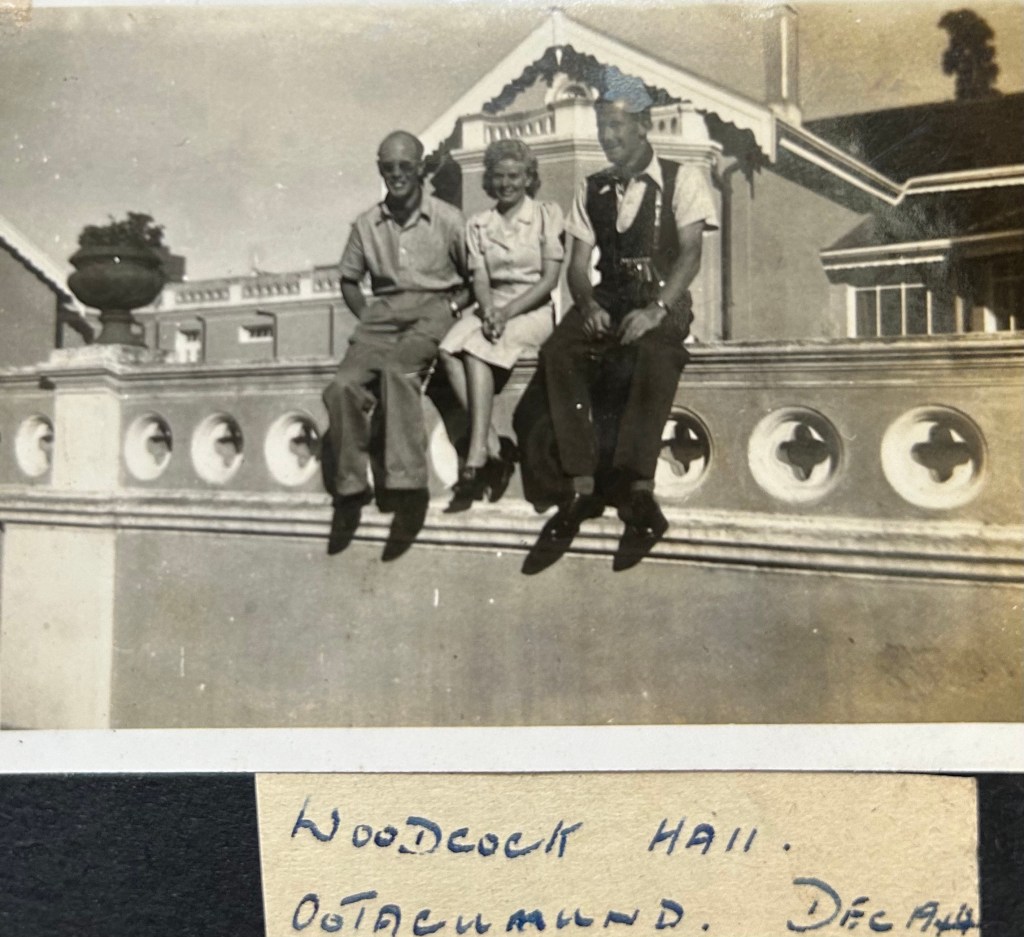

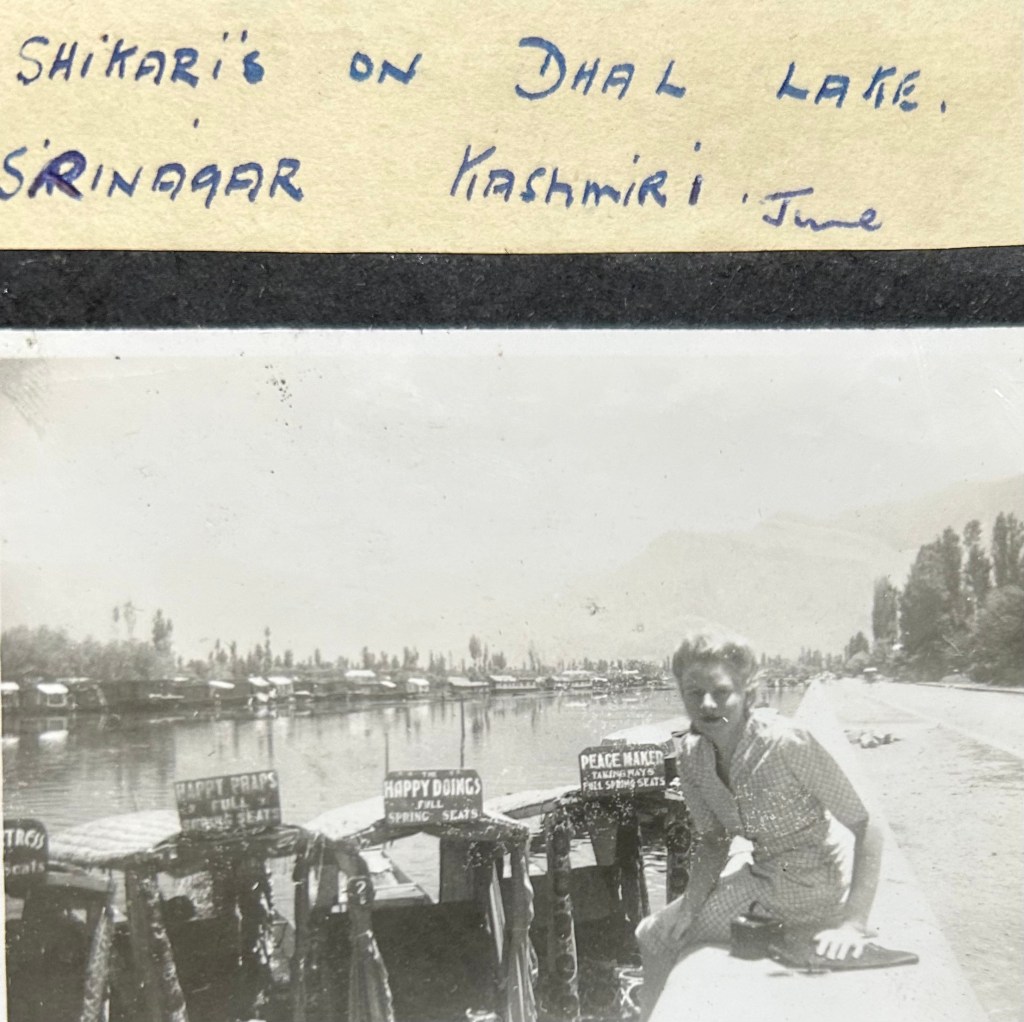

Eileen’s photograph album reveals that she spent time in Calcutta, Secunderabad, Ootacumund and Delhi and also went on holiday to Kashmir. Various accounts suggest that military nurses were treated well and enjoyed a good social life. This is certainly in evidence from Eileen photograph album.

The UK London Gazettes WWII Military notices register reveals that Eileen was a sister in the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) in late 1943 (Military Regiment number 294520). This reflects an initiative from the Sister-in-Chief at the time that all QAIMNS be given full military rank.

After the Japanese surrender in September 1945 Eileen transferred to Singapore.

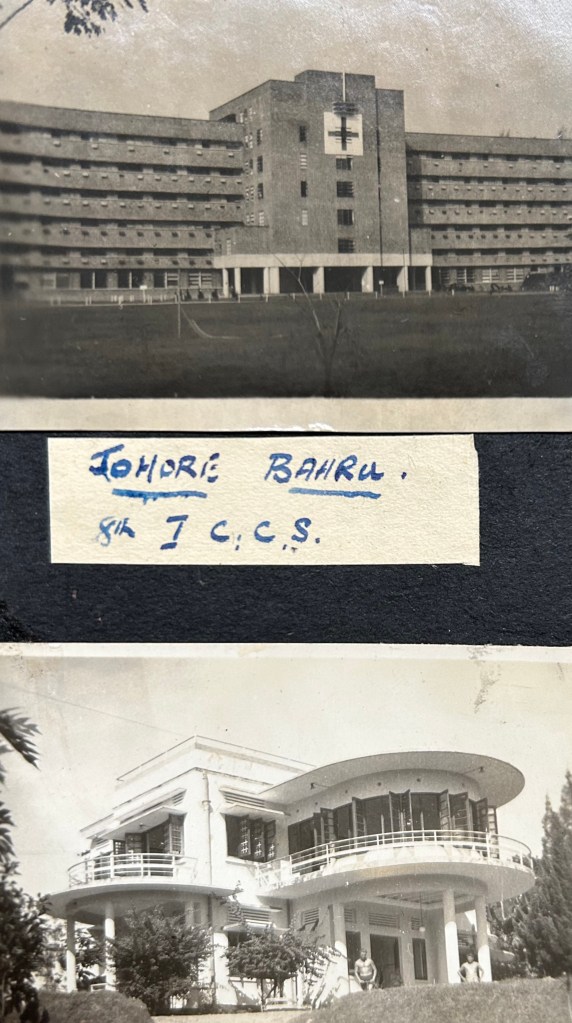

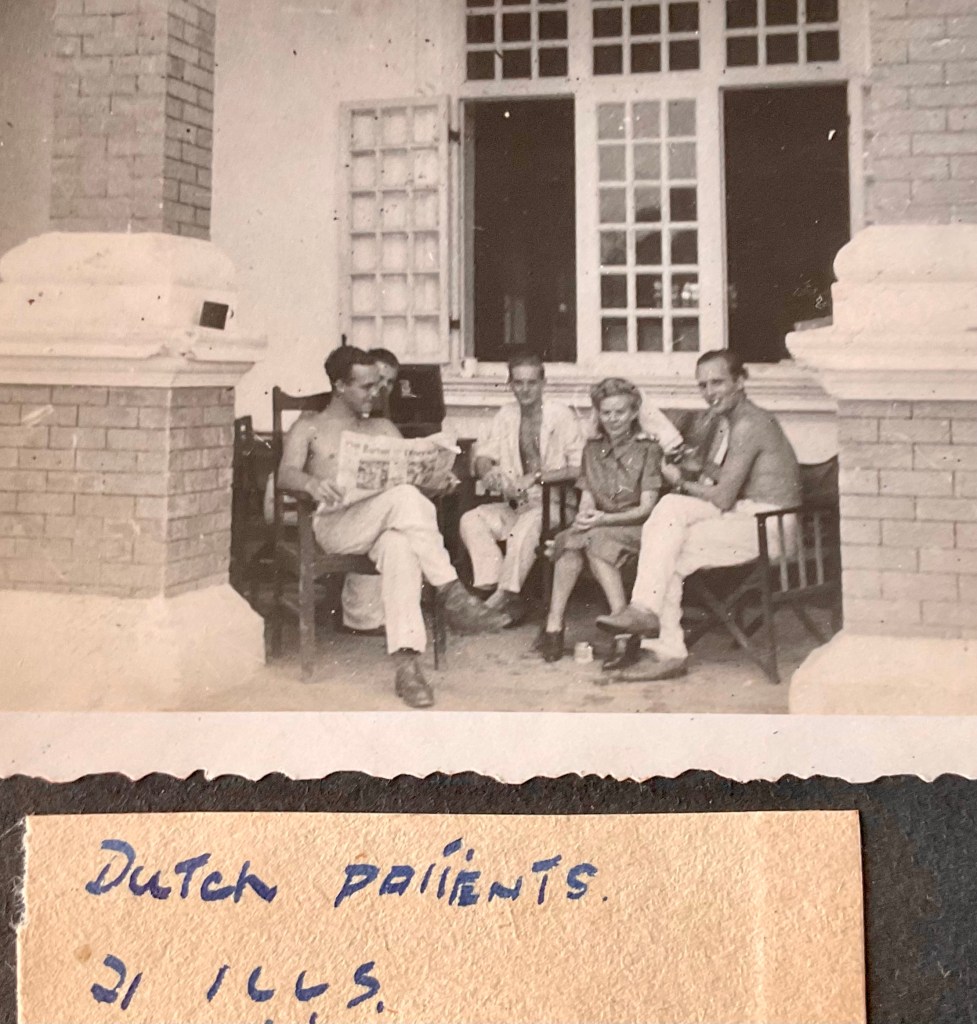

Eileen then moved on to Johore Bahru 8th I.C.C.S. Johore Bahru (just above the Singapore Strait) and Kuala Kangsar (North of Kuala Lumpur) where she nursed many former Prisoners of War from the work camps in what was then called Malaya, and Burma.

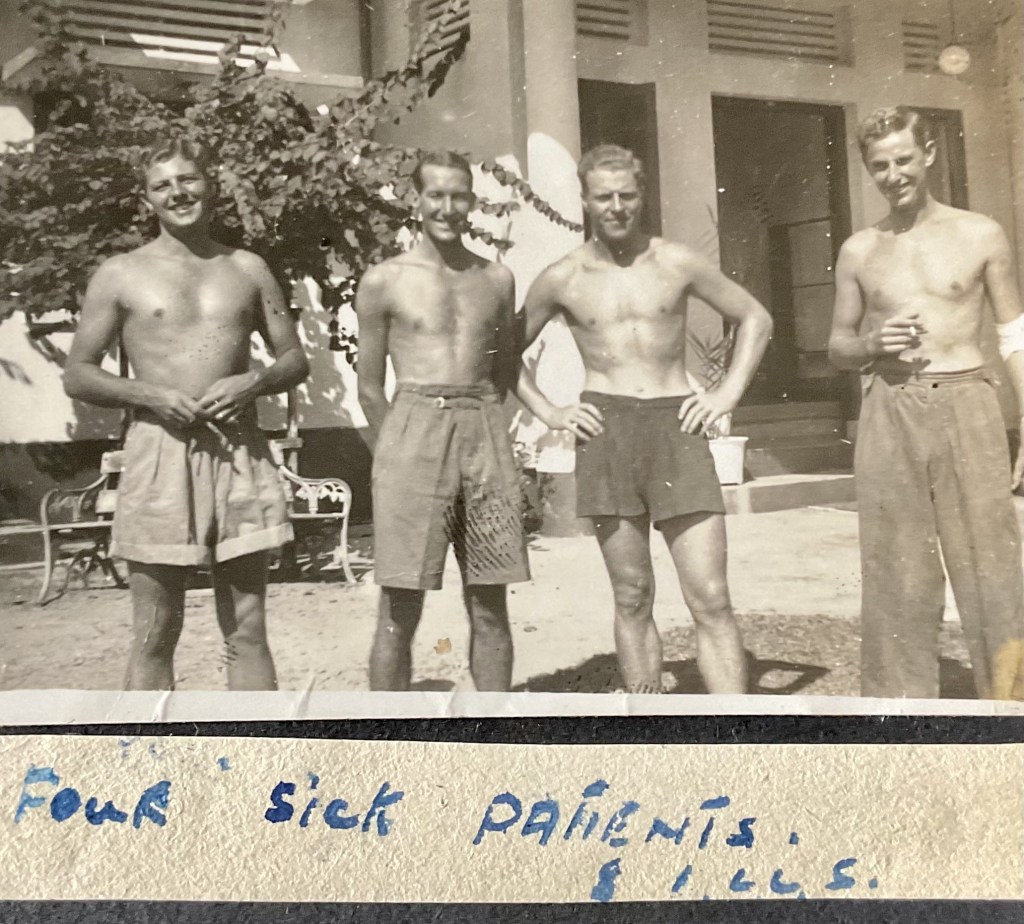

I recall that Eileen told me that she had been in charge of a ward of 100 very sick patients who were suffering from serious malnutrition, beriberi, a range of associated infectious diseases as well as serious mental anguish. In contrast to the cosy picture presented in TV dramas such as Tenko and the film Bridge over the river Kwai, she told me that many of the patients would hide their bread underneath their pillows as soon as anyone approached for fear that their food would be stolen. The photographs below are from 1946 when those patients who survived would have been near to full recovery. Note that the windows are open.

There is strong evidence from the photographs that Eileen was with the same people in Singapore and Malaya as she had been with in India. Eileen is seated on the front row left hand side in the photo below and the sister seated front row right appears in numerous photos in her album. Eileen was also a bridesmaid at her wedding in what looks like an old English church.

It is believed that whilst Eileen was away, she met an army doctor from Scotland and it is believed that he came from Glasgow, and his mother, who Eileen visited on her return to the UK, lived in the well known Gorbols area of slum dwellings. There is certainly evidence from her photograph album that she was friendly with someone called ‘Mac’ whilst she was in India and Malaya (in the photo below I believe, from other photos I have that Mac is sitting directly behind Eileen far right). However, unlike many of her friends for whom she was a bridesmaid (I have numerous photos) she did not marry whilst she was abroad.

Eileen spent well over a year in Singapore and Malaysia and there is evidence that she took some leave with other members of her unit in July 1946 and we believe from other labelled photos that the above was taken at MoonLight Bay, Penang Island which is not far from Kuala Kangsar.

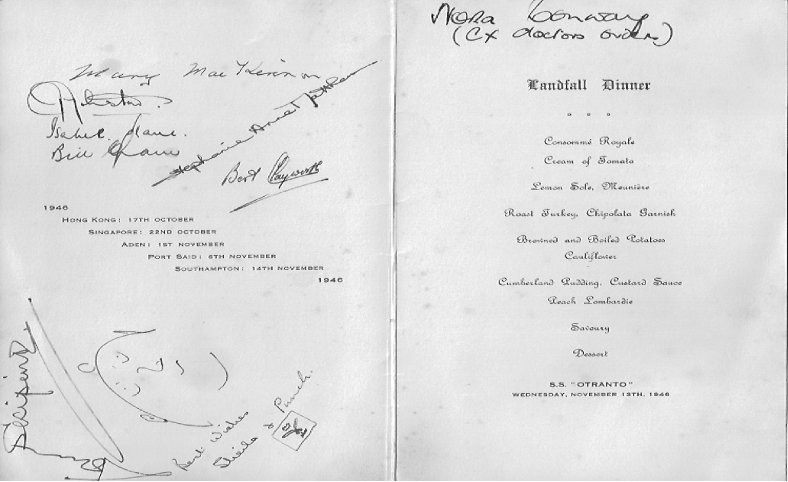

Eileen returned home – via Singapore – to England in November 1946 aboard the SS Otranto.

Return to the UK

Eileen subsequently returned to live at 1 Letchworth Drive Chorley with her mother and Hughie who had returned from the war by then having served in the RAMC as a pharmacist at the Pebbles Hydro Military Hospital Scotland, the D Day beaches of Normandy, and military hospitals in Bayeux, Brussels and Nigeria.

Nursing records reveal that Eileen worked as a sister at Chorley Hospital. It is known that she spent some time working on the children’s ward and subsequently qualified as a midwife and worked on the maternity ward during the post war baby boom period. It is believed that she became Deputy Matron but we have no written evidence of this. She continued to work at Chorley Hospital until a month before her marriage in December 1955.

It was during her period at Chorley Hospital that she demonstrated her appreciation of the importance of fresh air. Several people, including my late mother, told me that she would insist that the windows be thrown open for at least part of every day even in the depths of winter.

Eileen was strongly committed to the NHS formed in 1948, having previously worked under a patchy voluntary and private health system. This commitment was unwavering which meant that she refused to pay for a private hip replacement operation later in her life and this probably led to her untimely death in 1984 (see below).

In December 1955 Eileen Carlotta Smith, married Harry Stafford Mellor, a bank executive at Martins Bank HQ in Manchester, at the United Reformed Church, Hollinshead Street, Chorley. At this point, like many women in the 1950’s Eileen gave up work and became a full time housewife.

The couple lived in a large bank flat at 58a Woodlands Road, Ansdell, nr Lytham St Anne’s. The couple did not have any children and Eileen would spend her days shopping, cooking with 1950s gadgets (including a food mixer which I had never seen the likes of before), cleaning the flat and gardening.

She was clearly proud of what she had achieved in the war and subsequently. Despite her lack of a clear role she always possessed a certain independence of thought, and determination.

During the late 1950s and the 1960s my parents and I were regular visitors to Ansdell and on many occasions in the late 1950’s and early 60’s I would stay there on my own with Eileen and Harry and during the summer Eileen would take me to the beach, to the open air lido in St Anne’s, or to Fairhaven Lake which was only about 5 minutes walk from the flat.

Once again Eileen demonstrated her enthusiasm for fresh air. If I arrived with a cold or similar the windows would immediately be thrown open regardless of the weather. My mother would sometimes joke about it, but on reflection it was important, particularly as my elderly grandmother, Rachel Ellen was often staying there.

My grandmother (left of above photo taken at St Annes beach, Eileen centre, my mother right) went on to spend an ever increasing amount of time at Ansdell and was looked after by Eileen until her death, aged 93, whilst she was staying at Letchworth Drive Chorley in November 1978.

Harry Stafford Mellor died of cancer, which he originally developed circa 1974, on 27 December 1982, nursed by Eileen to the end.

Health Problems

From the mid 1970s on-wards Eileen was not in good health. She suffered from rheumatoid arthritis which worsened during the very hot summer of 1976. At the time it impacted mainly on her knees and hands. In 1980 or thereabouts she developed significant problems with her lower back and it was considered that a hip replacement would be beneficial to her. She refused to pay for the operation to be performed privately because she had a strong commitment to the NHS and she went on to spend over three years on a NHS waiting list. During this period she had to take an increasing number of drugs to attempt to manage her condition and she became increasingly frail.

Unfortunately, in about February 1984 the hip disintegrated and she could not move or get out of bed. She was admitted to Blackpool Victoria Hospital for an emergency hip replacement. However, she developed an infection in hospital and the hospital consultant said he could not operate until she recovered. She was then moved to the South Shore Hospital Blackpool, (which no longer exists), and showed increasing signs of deterioration. At this point the hospital tried to get her moved to a nursing home but she refused, insisting that she wanted to stay in the hope of receiving a hip replacement.

By October it was clear that Eileen was becoming worse and she was moved to the Blackpool Infectious Diseases on Devonshire Road where she had done her training as a nurse. I do not know the exact nature of her infection but full barrier nursing was implemented which meant visitors were required to wear special clothes and headgear.

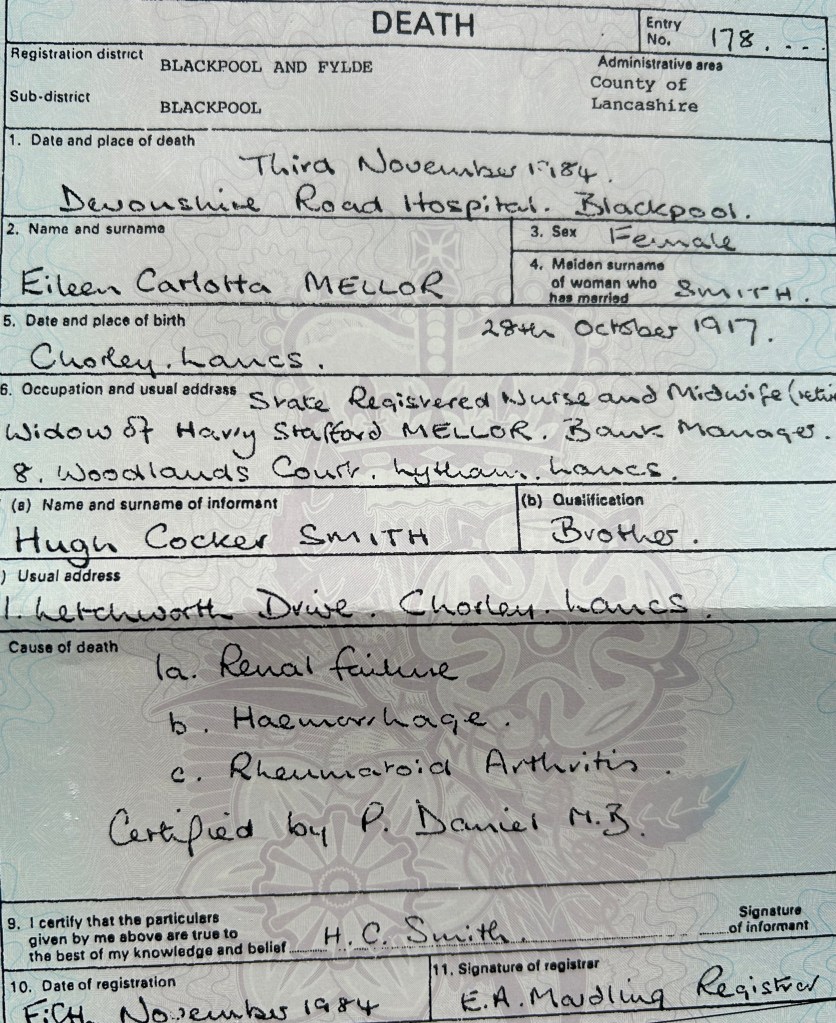

Sadly Eileen died on 3 November 1984 a few days after her 67th birthday. The death certificate records the cause of death as: renal failure, haemorrhage, and Rheumatoid Arthritis. It does not mention an infection even though she died in what was an infectious diseases hospital.

Concluding Comments

As explained in the introduction my purpose in publishing Eileen’s story on this website is to draw attention to her fastidious attention to good ventilation throughout her life, and highlight what an asset she, and others from that era and experience, would have been during the current pandemic. All that Eileen had then was bringing in clean air from outside at the same time as keeping the patient warm. I am sure she would have been quick to grasp the importance of modern methods such as HEPA filters and been quick to install them. This probably came from her training as an infectious diseases nurse in the 1930’s, a period when there were relatively few medicines compared with now, and nursing patients back to health depended on good care and a healthy clean environment, including clean air.

This basis for nursing was established by Florence Nightingale who back in 1859 was championing fresh air and called for the air inside the hospital ward to be as clean as the air outside through improved ventilation and air flow.

Leave a comment