Last year was an exceptionally busy year at the Covid Inquiry. Public hearings were held on no fewer than six of the 10 modules. In addition the major report of modules 2, 2a, 2b and c on political decision making was published in November 2025. This short blog focuses in the main on what has emerged from these key module 2 reports and hearings, and briefly outlines what is happening in the forthcoming year at the Inquiry.

Module 2 report published

The headline messages from the four module 2 reports (covering the UK, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) are summed up in the following paragraph from the executive summary:

The Inquiry finds that the response of the four governments repeatedly amounted to a case of ‘too little, too late’. The failure to appreciate the scale of the threat, or the urgency of response it demanded, meant that – by the time the possibility of a mandatory lockdown was first considered – it was already too late and a lockdown had become unavoidable. That these same mistakes were repeated later in 2020 is inexcusable. While the nationwide lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 undoubtedly saved lives, they also left lasting scars on society and the economy, brought ordinary childhood to a halt, delayed the diagnosis and treatment of other health issues and exacerbated societal inequalities. The Covid-19 lockdowns only became inevitable because of the acts and omissions of the four governments. They must now learn the lessons of the Covid-19 pandemic if they are to avoid lockdowns in future pandemics.‘

Key themes identified as a basis for doing better in future are:

- The need for proper planning and preparedness;

- The need for prompt and effective action to combat a virus;

- Scientific and technical advice – the effectiveness of SAGE’s advice was constrained by various factors as discussed in the separate section below;

- Vulnerabilities and inequalities The pandemic affected everyone, but the impact was far from being equal. It is disappointing that the clinically vulnerable families group was not part of this module, but it is encouraging that this point about unequal impacts appears to be a central conclusion of these module 2 outputs.

- Government decision-making – the report also clearly states that ‘ At the centre of the UK government there was a toxic and chaotic culture.’

- Public health communications – conflicting rules and communications caused confusion, and allegations of rule breaking by ministers and advisers caused huge distress and undermined public confidence in their governments.

- Legislation and enforcement

- Intergovernmental working needs to be improved

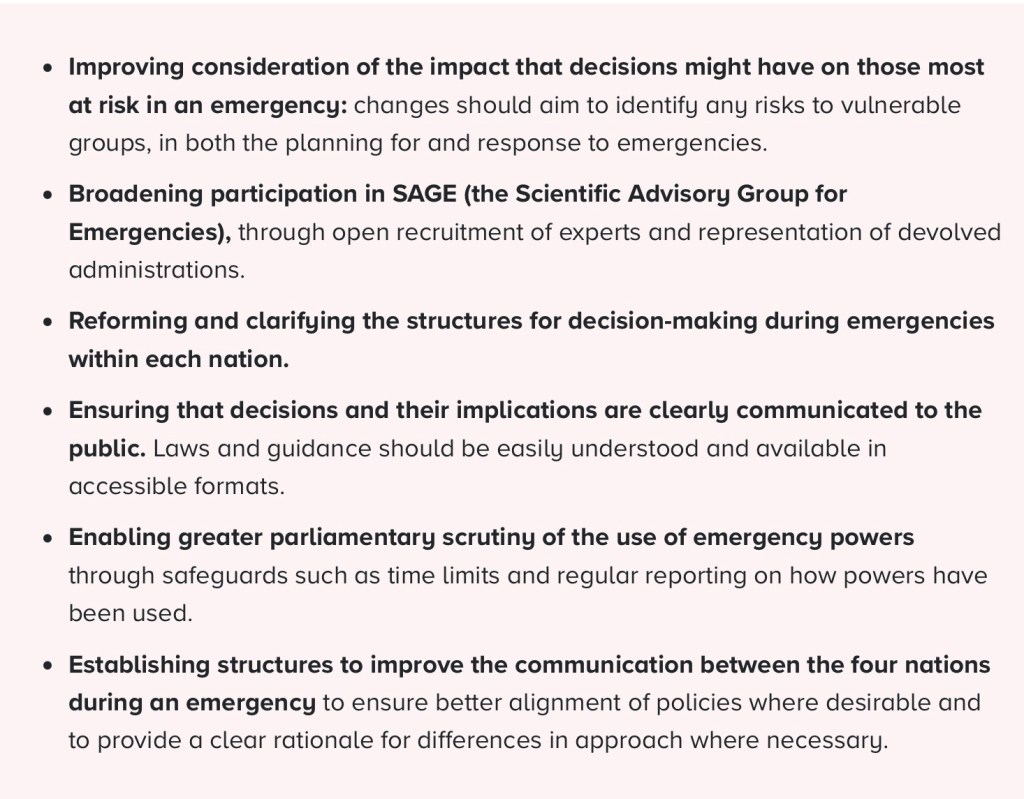

The key recommendations are captured in the following bullet points.

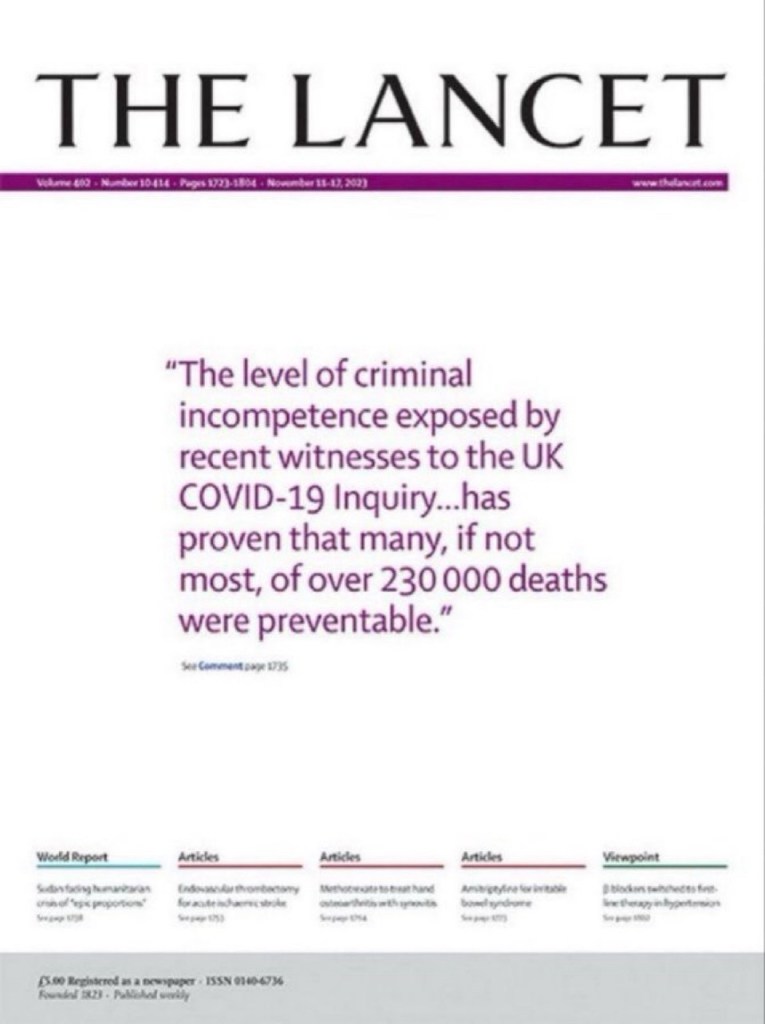

Most independent analysts agree with the main thrust of the conclusions, including that many tens of thousands of lives were lost that didn’t need to be, including the lives of many clinically vulnerable people who were disproportionately affected. In the first wave alone, which was not the most deadly period of the pandemic, the inquiry report says: ‘Modelling shows that in England alone there would have been approximately 23,000 fewer deaths in the first wave up until 1 July 2020’.

Moreover, tens of thousands of people have been left with devastating long-covid symptoms, again including many clinically vulnerable people who tend to be more likely to develop Long Covid. Staff working in the NHS, care services and other crucial services were exposed to unimaginable pressures from which they and the healthcare system have not recovered. The amount of societal and economic disruption suffered was, and continues to be, huge including for many clinically vulnerable families who have been left to navigate a society that pretends to move on from the pandemic whilst doing very little to help those left exposed to the continuing dangers of Covid-19.

Although the report is focused on the UK, we know that the UK spent more time in lockdown than most comparable countries, including those not so fortunate as the UK in the sense that we were hit by the first wave relatively late compared with some countries . I captured the experiences of my household during of the early phases of the pandemic in a blog on ‘Missed opportunities: the first 83 days of 2020’. A great deal of what this says is reiterated in the module 2 conclusions. Overall, the month of February 2020 was surely one of the most tragic examples of missed opportunities in UK history .

Media coverage of the report at the time of publication in late November was somewhat shallow and sometimes confusing, often implying that this was the only and final output from the inquiry.The Guardian coverage was better than most, but still had a tendency to focus on the political chaos at the centre of government, correctly drawing out the consequences of not taking speedy action to suppress the spread of the virus in February and the Autumn of 2020. What the media coverage failed to do is signal that there are a number of meaty reports still to come which could act as a basis for implementing lasting change in the short – medium term and placing us in a far more secure position when the next pandemic comes along.

Predictably those who were key players at the centre of government at the time have tried to dismiss the module 2 report, including PM at the time, Boris Johnson who attempted to shrug it off as muddled and inconsistent.

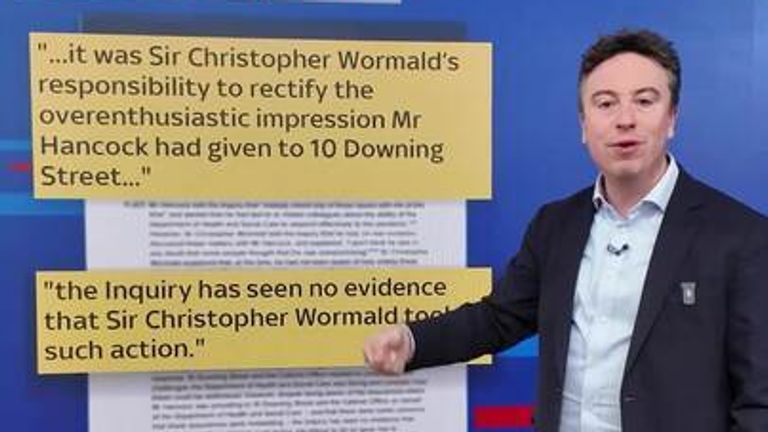

The current Cabinet Secretary, Sir Chris Wormold appointed in late 2024 by Sir Keir Stammer, does not come out of the report much better, something that the module 3 report from the Inquiry is likely to reiterate given Wormold’s performance at the module 3 hearings in late 2024 – see my blog on module 3. Wormold has yet to react to the report.

Scientific Advice?

As noted above, the report acknowledges that the main scientific advisory group – SAGE – provided high-quality scientific advice at extreme pace throughout the pandemic.

However, it goes on to note that there was no systematic process in place to ensure that it provided sufficient breadth of scientific expertise, with participants recruited through existing networks and professional connections.

And the effectiveness of SAGE’s advice was also constrained by the limited information provided by the UK government on its overall objectives when advice was commissioned. This made it harder for SAGE to place its advice in the right context.

Also, significant concerns were raised about the quality of economic modelling. This inevitably hampered the ability of decision-makers to assess and balance relative harms of various options .

And the process for providing advice on the economic and social implications of decisions was also much more opaque than for hard scientific advice. The lack of transparency of this economic and social advice, together with the repeated use of ‘following the science’ and similar phrases in communications to the public, gave a misleading impression that decisions were being taken solely on the basis of advice from SAGE.

In a recent blog Professor Anthony Costello, of ‘Independent Sage‘, provides a critique of the organisation of and impact of scientific advice in the emergency phase of the pandemic.

He sums up the problems with the organisation and composition of the provision of scientific advice as follows:

‘A pandemic is a scientific challenge only if we take a broad model of ‘science’ – biopsychosocial rather than biotechnical. Experts should be transparent, independent, diverse and candid. Observers should include civil servants, state advisers and Ministerial scientists but they should not dominate. All SAGE experts were good people, who gave their time generously, the independents voluntarily and unpaid. They discussed the challenge from their own disciplinary perspective. But the SAGE was not a PAGE, a pandemic advisory group for emergencies. The balance was wrong. The focus was biomedical and mathematical. Public health was missing. Professors Vallance and Whitty were independent advisers, not career civil servants. They had a duty to use their independence to speak out for the UK population, even if the politicians didn’t like what they said’.

Costello goes on to note that ‘a culture of openness was conspicuous by its absence‘.

The government did not seek to bring in expertise from a wider range of disciplines, particularly the social sciences. There were no experts on public health nor from emergency care experts working on the front line. Neither was there any international expertise despite it being obvious that some countries were managing to manage the pandemic far more effectively than the UK was. It is indeed difficult to argue against the conclusion drawn by PM advisor Dominique Cummings that SAGE acted as a kind of echo chamber. The consequences were tragic.

In Costello’s assessment there was a kind of calculated science and:

‘A strong system would admit mistakes and make do reforms. That didn’t happen. The ‘state of non-communication’ of our senior advisers remained impervious to criticism. They failed to respond to advice from independent groups of public health scientists and practitioners. They didn’t bring independent public health voices onto SAGE even when slammed by the Health Select Committee. They stuck to their lethal strategy of pandemic influenza and the omertà imposed on their advisers, to not comment on policy. They endorsed their political masters who saw public health measures as a threat to economic success.’

This is pretty devastating stuff, yet we saw it in action at various points at the height of the pandemic, not least over infection protection and control measures in healthcare and other settings. It is arguable that ‘groupthink’ and insularity within Public Health England and then at UKHSA led to critical evidence on how Covid-19 transmits, essentially that it is airborne, to be elbowed into the long grass with fatal consequences. It is hoped that Baroness Hallett will hammer home the key shortcomings in the organisation of and independence of scientific advice in all of her reports.

Key Activities due this year

This year also promises to be a very busy year. Module 10 hearings on the Impacts of Covid-19 on Society will take place between mid February and early March 2026. This module will focus on the wider societal impacts of the pandemic, including the impacts on the mental health and wellbeing of the population and at bereavement issues including visiting and funeral arrangements . It is hoped a key aspect of the module will be on the unequal impacts of the pandemic and associated measures on different groups in society, including the consequences for clinically vulnerable families. It is encouraging that the CVF group have been granted core participant status in this module as it is a chance to get across the continuing inequalities and hostility that CV people and their families face. The module will also pick up a range of issues in danger of falling through the cracks of other modules including the impacts on those in the criminal justice system, housing issues, support for those suffering domestic abuse, and people in the immigration system.

We are also expecting five reports on the various modules to be published in 2026. This includes the much awaited report on Health and social care due to be published on 19 March, following ten weeks of hearings held in Autumn 2024 – see my blog on this module. This should provide some key pointers on what the final report will recommend on key issues around Infection Prevention and Control measures in various settings – this includes the failure to provide appropriate PPE to healthcare and other frontline staff and failure to advise the public accordingly about the type of mask to wear and the importance of good ventilation . It is hoped that this module report will expose the flawed messaging from central government about the fraught issue of droplet versus aerosol transmission which cost many lives, placed clinically vulnerable users of healthcare in danger and continues to do so.

Other reports due to be published this year are

- Module 4 on Vaccines and Therapeutics – publication planned for 16 April. This will hopefully expose the very significant inequalities between the high profile and well resourced vaccination programme, and the lack of action on therapeutics – in the words of Dame Kate Bingham, chair of the vaccine task force ‘lack of vim and vigour ‘ on therapeutics for people, most of whom are clinically vulnerable, who are not able to benefit from Covid-19 vaccines. See my blog on module 4.

- Module 5 on Procurement -due to be published ‘in the summer’. This report will focus on the procurement of vital PPE and medical equipment and why the shortfalls, particularly in the first part of the pandemic, happened. It will also look at the VIP lane which gave fast tracked access to companies, often with good political and other connections. How these contracts were scrutinised and managed will be a central focus. It is hoped that the report will highlight the billions of pounds wasted on unusable PPE and equipment and raise questions about why no other country in the world found it necessary to introduce a VIP lane.

- Module 6 on the Care Sector – due to be published in ‘the second half of the year’ is likely to be critical of the way in which the care sector was, arguably, an after thought. Issues explored during the hearings included lack of PPE and inadequate infection prevention and control measures, lack of testing capacity, and decisions to discharge potentially infected older people from hospitals direct to unprotected care homes. The organisation of all parts of the care sector will come under scrutiny including staff burnout, illness, and on numerous occasions, deaths of care workers.

- Module 7 on Test, Trace and Isolate (TTI) – this report is also due to be published in ‘the second half of 2026’. A key theme here is the failure to recognise the importance of asymptomatic transmission of Covid-19 and the critical importance of testing in attempting to contain the virus and prevent it from spreading like wildfire . Following on from this the report may well conclude that there was a failure to harness the potential of local, mainly public sector facilities to ramp up targeted testing at speed early on, an approach strongly advocated by Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse. Baroness Hallett will need to weigh up whether this would have been better than relying solely on large private sector laboratories built from scratch which had the key disadvantage of not starting to come on stream much before the end of wave 1. The report will also need to consider the flaws with the stop start and very expensive and ill targeted TTI over time. In particular the failure to take account of the need to compensate workers for isolating themselves following a positive test and the loss of the huge monies spent on large new private sector laboratories which have subsequently been closed down with consequent loss of much needed capacity and learning .See my blog on this module.

- Module 8 on Children and Young People – the report of which is due to be published ‘in the first half of 2027’. This will need to address the lack of planning and early involvement of schools in decision making about closures, arrangements and support for on-line learning and arrangements for re-opening. It will need to scrutinise the over optimism about opening schools in summer 2020, including the lack of provision for key infection, protection and control measures in schools. It is hoped that the report will also expose the folly of the ‘one size fits all’ approach and the failure to take account of the needs of different groups in society, including clinically vulnerable children and children living in clinically vulnerable households who needed continuing support rather than the punishments, bullying and illegal off-rolling with the consequent loss of education that many suffered. See my blog on this module.

The reports of the remaining two module reports – module 9 on the Economy andModule 10 on the impacts on society will also be published in ‘the first half of 2027’. The final report is also expected to be published in 2027.

Concluding Comments

It is hoped that the emerging module reports and the final report will act as a springboard for the introduction of measures which will place the UK in a far better position to plan for and manage the next pandemic when it comes along. It is hoped that the inquiry will also trigger the introduction of measures in the short – medium term to improve the health and wellbeing of the population as a whole as well as paying attention to the societal groups that did not fare well. This includes clinically vulnerable people and their households. In particular it is hoped that the report will be a springboard for giving CV people the recognition they need in equalities laws in order to ensure that they are never again overlooked in pandemic planning and implementation in quite the way they were.

However, despite the change in government since the height of the pandemic it is far from certain that there is real appetite for change at the centre of government. I know few people who are overly optimistic about the labour government in this respect.

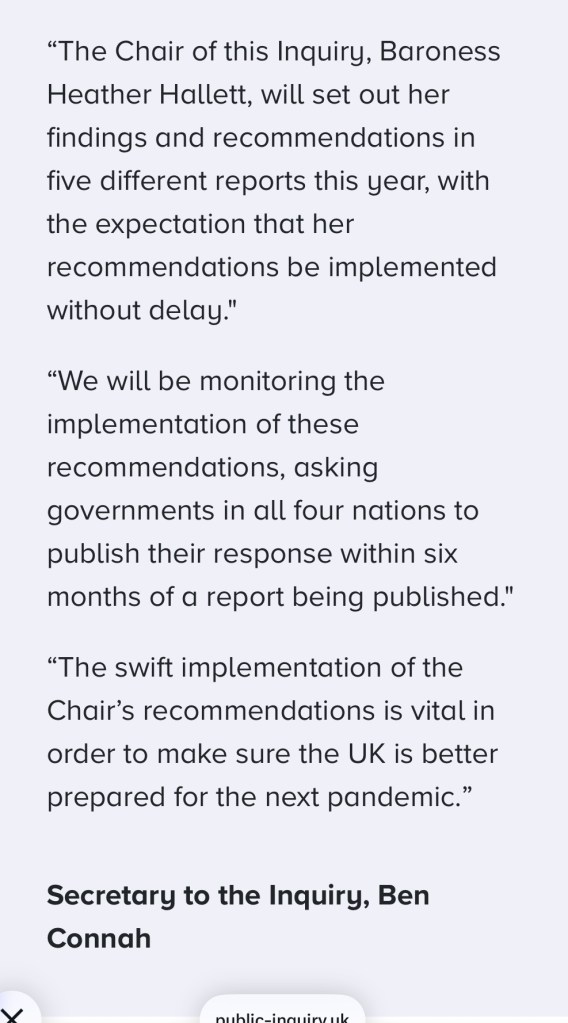

As Baroness Hallett has said on several occasions, she expects the recommendations in the module reports to be implemented without delay. On 13 January 2026 she firmed up further on this and said they were asking governments in all four nations to be publish their response within six months of reports being published.

The slowness in the response from the government to date is not particularly encouraging, however . I find it difficult to be optimistic that fully implementable, costed and approved responses will appear on this timetable along with real commitment and energy to implement them without delay.

There are said to be about 200 people working at the centre of government in order to formulate responses to and implementation plans on the reports that will emerge from the inquiry. The key danger is that some of these people will have been in post at the height of the pandemic and the fear is ‘groupthink’ – a key problem highlighted in the outputs from the inquiry so far, will continue to be in alive and kicking amongst officials in government and associated bodies. This could result in government responses that are overly defensive and not sufficiently focused on looking forward with fresh eyes.

We know that Baroness Hallett is aware of this problem. Indeed she has previously indicated that her reports will be the beginning and that it will take real pressure to ensure the messages are implemented in full.

Hallett has previously called for the core participants to the inquiry to continue to push for change once the ink on her final report is dry and it is no longer in the media. This is of course a mammoth task given that many of the core participants, including the CVF group, the Long Covid groups and the bereaved families are reliant on small groups of volunteers, many operating with health conditions or caring and work responsibilities and with home computer equipment. The inequality between the resources of many of the core participants and government departments could not be starker. Nevertheless, these groups, including CVF, have notched up some significant wins to date and need to be seen as key players.

It is also hoped that pressure will continue to be exerted by independent academics, professional groups, trades unions and pressure groups willing to be proactive in challenging governments and associated bodies by continuing to raise the issues and putting pressure on to implement the recommendations. In my assessment we need a body such as Independent Sage to take on the task of pushing for implementation but they would need resources to do this. Where appropriate, this advocacy also needs to draw upon pressures from International Organisations pushing for the same things – see a recent blog from Valbhav Agrawai.

We also need parliamentary champions to keep the issues on the agenda combined with a significant amount of well led parliamentary select committee activity.

In sum, the statement that the publication of the final report will be the beginning and not the end rings true. Everyone who has given their time and energy to the Inquiry to date needs to work to ensure the report does not sit gathering dust like so many public inquiry reports to date.

Finally, I would also like to make a plea and encourage you to support the Clinically Vulnerable Families latest crowdfunding appeal – please pledge your support here. Thank you.

Gillian Smith

17 January 2026

Leave a comment