Module seven of the Covid Inquiry is of critical importance as we know that having effective testing, tracing and isolate policies is one of the keys to managing down and suppressing viruses such as COVID-19. Indeed the fact that some countries were able to draw on their experience of and infrastructures put in place to tackle the SARs epidemic earlier in this century enabled them, South Korea and Taiwan, for example, to avoid national lockdowns at the same time as having a death rate from Covid-19 that was tiny compared to the UK.

The UK performance was abysmal by comparison with these countries and was also inferior to many Western European countries. We need to learn the lessons on why and what could be done differently in the future.

This short blog is an overview of the module 7 hearings and focuses in particular on policy decisions and practice in the early days of the pandemic, particularly on testing policy and capacity and assumptions about asymptomatic transmission. As I have not had the chance to watch the sessions on Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland I tend to focus on the UK wide or English experience.

Tragic Consequences

The Covid Inquiry Module 7 hearings began on 12 May with powerful testimonies from those most impacted by the pandemic, including the relatives of those who died as a result of policy failings around testing policies and practices. It heard from Hazel Gray who lost both of her parents in late 2020 almost certainly due to carers for her parents bringing the virus into their home. To her astonishment she was told by the organisation providing their care that carers were not tested despite regularly going into the homes of vulnerable people often without or with very basic PPE (see video below).

The Inquiry also heard from another lady who had talked her mother into going into hospital due to a severe burn only for her to die of Covid at least in part due to a failure to effectively separate non Covid patients from Covid patients due to a lack of testing.

Background to Policy

Despite the evidence of asymptomatic transmission of Covid-19 from early February 2020, and the innovative attempts at test, trace and isolate being practised in some other countries, the UK government was essentially following a flu strategy in the early days of the pandemic. This was without doubt a major error. The two main problems were:

- it failed to take account of the differences in severity between the two illnesses, and

- it failed to recognise the prevalence of asymptomatic transmission of the Covid virus (meaning that large numbers of people – possibly as many as 40% of Covid infected people were carrying and spreading the virus without knowing they were ill).

This combination meant that population testing for the virus was far more important than with a flu virus, yet the failure to recognise this was part of the reason for the UK decision to halt first attempts at test and trace on 12 March 2020.

This failure also reflects the significant weight being given to the idea of building up herd immunity across the population during the early days of the pandemic – see my earlier blog on the first 83 days of 2020. This meant no serious consideration was ever given to suppressing (which would have required a Far East type functioning test, trace and isolate approach), as opposed to attempting to contain and manage the spread of the virus.

The consequences were profound. Professor Anthony Costello of UCL estimates that this failure to suppress the virus cost in the region of 180,000 lives across the UK.

Testing Capacity and Practice during Wave One

Sir Paul Nurse, Head of the Francis Crick Institute in London, explained to the Inquiry in very clear terms just why testing for the virus was of critical importance and just how important getting the results back quickly in order to identify and quickly isolate healthcare, care staff and other key workers so they would not be passing on the virus to often vulnerable patients and people.

Yet lack of capacity to test enough people was without doubt a key barrier, particularly at the start of the pandemic. The government took the decision early on in March 2020 that large scale testing capacity needed to be built from scratch and this led to the construction of a number of large private sector labs called ‘the lighthouse labs’ which were designed to operate what then Secretary of State Matt Hancock described as on an industrial scale. The key problem with this was it was not possible to get these up and running and functioning at scale until towards the end of the devastating first wave of spring 2020.

The UK’s failure to achieve the required speed and volume during the first few months (and later) of the pandemic meant many tragic stories of the kind presented above where people died because of the infection being passed to them by untested healthcare and other staff. Secondly, it meant large numbers of staff were having to isolate and take themselves out of the front line if they were symptomatic even though it sometimes emerged that they did not have the virus.

Yet Nobel prize winner Sir Paul Nurse and others explained that they had a solution that would have helped to provide capacity in the early days, but the government failed to listen to them. By early February 2020 Nurse could see that his Institute could be quickly reconfigured to produce a 24 hour turn around Covid tests at a rate of up to 10,000 per day if they had a bit of seedcorn small scale funding. The Crick also had 300 volunteers coming forward with what he described as a public service ethos’, people who would otherwise be furloughed. He also told the Inquiry that there were between 40 and 50 Research Institutes and Universities across the UK that could be reconfigured at pace and turn out much needed testing quickly and the people I have spoken to confirm this.

The Crick Institute and one or two other labs went ahead on their own initiative and funding and provided an invaluable service in their local areas. But without Government interest they could not ramp up to thousands of tests per day and the model could not be deployed across the 40-50 other labs. The consequence was that to the dismay of senior Professors in some of these locations they were ordered to send skilled staff, willing and able to volunteer off on furlough and some of their equipment was moved to the Lighthouse Labs.

In the following video Nurse summarises some of the implications of the lack of testing capacity, as well as why the existence of asymptomatic transmission was important in this context.

It is pertinent to note at this stage that Nurse was not saying that these big industrial scale labs were not needed; what he is saying is that his model could have provided the locally nuanced and fast service targeted at healthcare and other key workers early on in the pandemic.

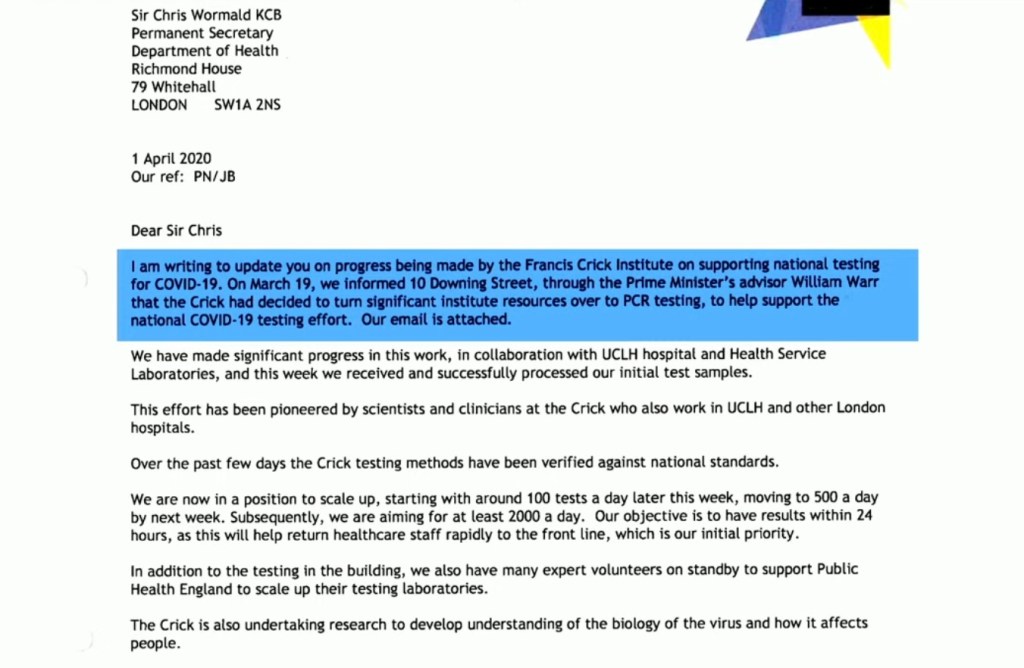

It is not at all clear from the evidence whether Nurse’s proposal was simply overlooked or whether there was open hostility from within government. What is not in doubt is that Nurse was lobbying the Government about the issue from an early stage. See the following piece of correspondence addressed to the then Permanent Secretary of the DHSC (now Cabinet Secretary) for example.

Along with a general lack of interest in the ‘Nurse’ model, perhaps the key point to emerge from the evidence given by Sir Paul Nurse is the apparent lack of interest and unwillingness within government to test all healthcare and other staff coupled with a failure to recognise the scale of and importance of asymptomatic transmission of Covid-19 to vulnerable people. The following series of correspondence illustrate the issue.

The above letter from not one, but two Nobel Prize winners who were trying to help did not receive a response from the Secretary of State. The only reply received was on 6 July – nearly three months later – from a junior civil servant at the Department of Health and Social Care (letter reproduced below). It is notable that the key point about the need to take asymptomatic transmission into account when devising a testing strategy is ignored.

The Government Response on Testing

In his evidence session which was at times bad tempered, former Secretary of State for Health, Matt Hancock defended the decision to focus on the industrial scale Lighthouse Labs, taking what is an obvious side swipe at Nurse, but at the same time failed to address the point about using smaller scale labs in a targeted way during the early stages which is what was being proposed by Nurse who likened the role they could have played to the small boats at the Dunkirk evacuation. Indeed at one point, chair Baroness Hallett had to intervene to make it clear that the position taken by Nurse was not, as Hancock claimed, about ‘bruised egos’.

It will be interesting to see what Baroness Hallett makes of the competing pieces of evidence heard about arrangements for increasing testing capacity during those crucial early stages of the pandemic.

Asymptomatic Transmission

As discussed above, it seems on the face of it there seems to have been some confusion in the minds of some politicians about the science behind whether Covid-19 was present in people without symptoms and whether it was possible to test for this. This in turn, led at least in part (along with testing capacity) to a failure to test all healthcare workers, care staff and patients during much of 2020 sometimes with devastating consequences.

The key Minister at the time, Secretary of State for Health, Matt Hancock, told the inquiry that before 14 April 2020 his understanding had been that the science suggested that testing for asymptomatic transmission of Covid-19 was not effective . He went on to say he was delighted when it was confirmed that it was, as the fact that patients were being transferred back to care homes from hospitals without testing was something that had been worrying him.

However, this is at odds with what then Government Chief Scientist Sir Patrick Vallance told the Inquiry about what he understood the position to be on 11 March 2020 regarding what had been said to the Secretary of State around that date ie. clear evidence of asymptomatic transmission, testing does pick up many cases, but may not pick up everyone who is carrying the virus, so there is a need to keep testing.

A month went by and according to Vallance he became aware on 14 April that the Secretary of State still had an incorrect understanding of what he had been briefed about earlier, and seemed to think that testing for asymptomatic transmission was not effective. Please watch the following clip in which Vallance explains what he did when he heard that the Secretary of State had an incorrect understanding ie he checked that he was on the same page as the Chief Medical Officer (Whitty – confirmed) and arranged to someone in the Government Office for Science to write an urgent note restating the position with no room for ambiguity. This is the point at which the penny seemed to drop with Hancock but the problem was that by this stage thousands of people had been transferred back to care homes from hospitals without any testing being done.

There are obvious key lessons that can be drawn from this story about ensuring that the science is clearly understood by those taking decisions at any particular point in time. This is not a new issue of course but it will nearly always be critical to get it right in an emergency.

Mid – Late 2020/2021 – Operation of Test, Trace, Isolate

Fast forwarding slightly, by May 2020 it was evident that wave 1 of the virus was coming to an end and tentative steps were being made to begin opening up society after the first lockdown. By this stage Baroness Dido Harding had been appointed to head the NHS Test and Trace programme in England which was eventually given a budget of £37billion. Most of the work was contracted out. The overall purpose was to create temporary sites to test people, process the tests at a network of Lighthouse Labs, communicate the results, instruct people who tested positive to isolate themselves and to provide a list of contacts ie people who the infected person had had contact with.

This was a mammoth task with an overall budget of £37 billion over 2 years. This is a huge sum by any measure and bigger than the budget of a number of government departments. To put it in context the annual budget of the UK Ministry of Defence is about £60 billion p.a.

The process of setting up the operation, including rapidly increasing testing capacity was not easy and there was a very heavy reliance on highly paid private sector companies such as Deloittes who sometimes had no relevant clinical knowledge. In his evidence Professor Deenan Pillay was critical of the way in which University Scientists with world class reputations and willing to work with the Labs were excluded from the process. Indeed there was a widespread perception that they were unwelcome.

In her evidence Baroness Harding told the inquiry that in her assessment a number of problems became evident. The two key points she highlighted in her evidence were, firstly, over optimism in summer 2020 that the virus had been defeated coupled with a return to business as usual modes of operation on procurement. Harding provided evidence that the return to a ‘business as usual’ mentality effectively introduced new barriers and slowed down the building up of testing capacity and contact tracing work. This meant that the second phase of testing laboratories was far slower than the first wave despite all the learning gained during the first phase.

Her second key point is that a refusal by the Treasury to provide sufficient help to people – particularly vulnerable people on low incomes/insecure employment – to isolate themselves and co-operate with the system meant the system of getting people to isolate in order to prevent the spread of the virus was never fully realised. This point was picked up in the media. Baroness Harding said she repeatedly raised this issue with the PM and with members of the Cabinet but that the then Chancellor of the Exchequer would not budge on it.

Baroness Dido Harding, who was in charge of the programme in England, told the Covid inquiry she repeatedly argued to increase financial support, but was “frustrated” by the response of then chancellor, Rishi Sunak.

This chimes with other evidence sessions including from Behavioural Scientist Professor Madelynne Arden which is essentially that people will only change their behaviour and isolate if the purpose is understood, it is easy/possible to do and people trust and have confidence in the system.

In sum it seems extraordinary that the government was potentially spending £37 billion on the Test and Trace system but refused to fund a measure that without which the system could not operate effectively. Baroness Harding was at pains to point out that she had said that funds should have been diverted from her budget in order to fund support to enable people to self isolate. It seems odd therefore that former Chancellor and PM, Mr Sunak has not been called to give evidence to this module of the Inquiry.

Vulnerable Groups

The specific needs and circumstances of clinically vulnerable people and their families were largely absent from the discussions across this module no doubt reflecting the fact that the clinically vulnerable families group was unsuccessful in a bid to be designated key participant status. An obvious issue missed is there was no discussion of testing to support clinically vulnerable people to attend healthcare settings safely.

There was however, some discussion and questioning around the circumstances of people on low incomes, insecure employment, the elderly and black and minority ethnic groups. The key point is the one highlighted by Baroness Harding above, that without extra support some people were simply unable to isolate themselves due to financial and other pressures.

Another key point is that some groups were more exposed to the virus due to the type of jobs they performed or because of their living arrangements, but these are the groups that found it most difficult to access testing facilities and access information in the right language and in a culturally appropriate way.

Numerous witnesses said that centralised testing policies were devised without reference to the idea that some groups and areas might need to be prioritised. Lack of trust in officialdom was also an issue in some areas. locally based staff with knowledge of local populations were sometimes able to work effectively with centralised systems but this was not always the case.

Baroness Harding picked this up in her evidence when she made the point that the remit she was handed was to develop a national system focused on delivering at scale. This meant for example, that the first testing centres, including at Chessington World of Adventures in Surrey, were opened in the locations which were easiest to get up and running quickly. The problem was that they tended to be difficult to access by public transport and tended to be used by people with access to a car who were willing to travel. She stressed that had she had a different remit, that included targeting those most in need of testing, the priority would have been given to opening centres that were easy to access by target populations.

Preparedness for the Next Pandemic

Several witnesses were asked about preparedness for the future and the responses did not make for happy viewing. The almost universal response was that we are not currently in a good place, with some witnesses saying we are now in a worse position than we were in 2020 in terms of our preparedness for getting a large scale testing system and a test, trace and isolate system up and running at speed.

Indeed when Professor Martin McGee was asked the question he looked down at his papers and said ‘oh dear’!

Even the former junior health minister, Lord Bethell made the following observations about the wholesale dismantling of the £37 billion laboratory capacity that had been put in place to ramp up testing and tracing. Whilst recognising the argument that it may not have been appropriate to keep these labs operating at full capacity, some way of using them to improve public health screening in a way in which they could be ‘fired up’ to operate on an industrial scale if needed should have been the aim. Instead of this they have been mothballed and the UK diagnostics industry has in the words of the former Minister ‘shrunk to almost nothing and is extremely weak’.

Similarly when Baroness Dido Harding was asked about the dismantling of the laboratories she said it was a missed opportunity to take public health seriously and how ‘prevention is so much better than cure’ and ‘ that vision of high throughput diagnostics capability coupled with a local targeted public health system that really looks after the people who would benefit most, ought to be one of the legacies of Covid’.

Professor Deenan Pillay evidence also reinforces this message on the need to rebuild an infrastructure that would ultimately save time and money when the next pandemic comes along – the aim being to put us in a similar place to where South Korea was going into the Covid pandemic.

But the point that he also touches on is how far the UK has gone backwards in terms of having a public health infrastructure. He explicitly states that the UKHSA is a shadow of the former public infrastructures that we used to have.

Concluding Comments

The three weeks of hearings have shone a light on the catalogue of issues and missed opportunities to put in place policies which Professor Anthony Costello of UCL says could have saved 180,000 lives. This blog has been a brief canter through some of the key sessions that I have watched

The hearings across this module tend to chime with The key overarching message from Professor Martin McGee of Independent Sage. He told the Inquiry that by October 2020 it was clear that the system was failing and that we were not learning the lessons from other countries. Independent Sage produced a document setting out what they way forward should look like but this was largely ignored by government at the time.

Overall the picture of what happened can be summed up in the words of Professor Christina Pagel in the following video clip from Channel 4 News screened just before the start of the module 7 hearings. “We were not willing to learn from what other countries were doing and ‘we didn’t try hard enough.

It is hoped that Baroness Hallett will be successful in getting across the need to take seriously the preparedness for the next pandemic in terms of building diagnostic capabilities and public health infrastructure that makes appropriate use of existing expertise and can be scaled up quickly. We clearly need to avoid being in a position of having to rely so heavily on highly paid consultants and setting up new infrastructures from scratch with the resulting huge expenditures – both human and monetary. Achieving this in the current political and financial climate, combined with the near denial about the impacts of Covid-19 and the UK failures, will require a fair amount of will and tenacity. The publication of Baroness Hallett’s report next year will only be the beginning.

Nevertheless bringing about a genuine focus on improving public health and rebuilding infrastructures would bring huge benefits now. The UK is still very much suffering the impacts of Covid-19 . Clinically vulnerable people and their families are still being prevented from participating fully in society and the economy, millions of people are suffering from long covid and illnesses caused by Covid-19, participation in the labour market has slumped significantly compared to European counties that managed Covid-19 more successfully, health inequalities have soared and the NHS is overwhelmed and focused on treatment rather than prevention.

Surely when a range of witnesses as diverse as a Conservative peer and former junior health Minister, a hereditary peer closely aligned to the Conservative Party and a range of senior scientists are all saying the same thing about the need to build the public health and diagnostics infrastructure surely this has to be taken seriously?

Gillian Smith

1 June 2025

Useful Resources

Week 1 BBC sounds Covid Inquiry Podcast

Week 2 BBC sounds Covid Inquiry Podcast

Week 3 BBC sounds Covid Inquiry Podcast

Also see the Covid Inquiry YouTube Channel

Leave a comment