The final hearing of the longest module of the Covid Inquiry, module 3, took place on 28 November 2024. This part of the Inquiry covering healthcare in England, Scotland, Wales and Norther Ireland, heard from 96 witnesses in total, and considered nearly quarter of a million pages of evidence.

It has been a rollercoaster ten weeks for the core participants, including the Clinically Vulnerable Families group (CVF), which was finally given a voice to air our perspective on a public platform. This blog is not meant to be comprehensive but seeks to provide some personal reflections on key issues that arose over the last ten weeks or so.

Preparedness

The inquiry heard extensive evidence on how the UK went into the pandemic with a healthcare system on the edge, and lagging far behind systems in most comparable rich nations. This points to the necessity of better preparedness and capacity within the healthcare system to manage pandemics in the future, including ensuring adequate staffing levels and a recovery of staff morale, upgrading the NHS estate, installing permanent and temporary means of ventilation, critical care capacity, bed capacity more generally, and adequate availability of essential resources like PPE.

How this is achieved is a political issue that is beyond the scope of the Inquiry Terms of Reference as the chair, Baroness Hallett, made clear several times during the hearings. Indeed, when Sir Sajid Javid pressed the issue she reminded him that his former colleagues had set her Terms of Reference to specifically exclude this wider funding, and models for the future issues!

Specifically on staffing, it was made clear throughout various sessions that staff on the front line had suffered and were suffering great harm from the sheer pressures and unimaginable horrors of working through the height of the pandemic with pressures continuing to this day. Reported problems include an increased chance of catching Covid and disproportionate likelihood of developing long covid; severe stress, anxiety and other illnesses that many have yet to recover from. Indeed many witnesses to the inquiry were keen to stress that support for staff was, and still is, inadequate. Unless this is addressed the healthcare system is very unlikely to recover to previous ‘peacetime’ operations (partly because we are not in ‘peacetime’ – Covid is still rampant) let alone stand in readiness for the next pandemic.

Was the Healthcare System Overwhelmed?

A number of witnesses from the previous administration and people still in key posts in central administration in the Dept for Health and Social Care, UK Health and Security Agency, the ‘Infection Protection and Control Cell’ and others told the inquiry repeatedly that the NHS coped, despite the pressures. What they tended to be talking about was’ that bed capacity never being exceeded at the national level, whilst acknowledging that there may have been local problems.

On the other hand, countless witnesses with front line experience as either a front line worker, patient or bereaved relative were universal in painting a very different picture of lack of safe capacity to the extent that people were denied access to the level of healthcare that was needed, including access to ICU beds.

On bed capacity, for instance, there was not, nor is now, an agreed measure, but several witnesses called for a common measure which should be number of beds occupied below or above normal ‘peacetime’ capacity. On the other hand many of the witnesses who claimed capacity was never breached nationally were basing their calculations on normal ICU or other beds plus the temporary beds created in operating theatres and other settings to deal with the surge in demand. These were not real ICU beds in that they were sometimes staffed at 1 nurse (who had often been drafted into working in an ICU role) to 6 patients rather than the normal one to one care.

The most moving testimony of the pressures faced by healthcare staff came from Professor Kevin Fong who was employed by Public Health England to go out and support some of the worst hit areas and described his experiences to a completely silent hearing room. The enclosed report from the Guardian newspaper captures some of his harrowing evidence. Also see one of the less harrowing clips from his evidence embedded in this article from the BBC. It was made very very clear from this testimony just how much pressure the system and staff were under and how patients were not receiving the standards of care one would normally expect. Fong’s evidence also illustrates very clearly just how limited monitoring data actually is in telling those in authority what is actually happening on the ground.

Indeed Baroness Hallett commented on the final day of the module hearings that never in her forty plus years as a senior judge had she heard anything quite like it. Further evidence on the dire situation in ICU departments was also provided by Professor Charlotte Summers and Dr Ganesh Suntharalingam.

Several witnesses, including Fong, also painted a grim picture of what was going on in settings away from the big city centre and town centre hospitals that the TV cameras tended to go to. It was explained that patients who ended up in hospitals without an ICU department would be assessed and those with the greatest chances of survival were moved to hospitals with an ICU. The prospects for the rest and the staff trying to care for them were not good.

In her evidence junior doctor Dr Tilna Tilakkumar, one of the impact witnesses for the BMA, described being sent to work as a clinician on a long stay mental health ward. When Covid-19 hit it spread rapidly because it was very difficult to keep patients away from others and maintain social distancing. For these patients there was little prospect of being transferred to a hospital setting let alone an ICU bed when they contracted Covid-19.

Outside of hospitals, ambulance staff including Mark Tilley, an impact witness for the TUC, gave evidence on the pressures of dealing with the sheer volume of calls to very sick patients and sometimes arriving at an address only to find the patient was dead on arrival or sometimes dying before their eyes whilst they stood outside putting their PPE on. Tilley also described having to wait, sometimes for many hours, outside hospitals waiting to offload patients into hospitals.

On top of the pressures of dealing with Covid-19 patients most of the treatments usually provided by healthcare providers stopped when the pandemic hit. This included cancer treatment, diagnosis and screening. I can testify to this myself as in the first week of April 2020 I remember very clearly going to collect some extra drugs which had been prescribed for my husband to try to compensate for the delay in his cancer treatment that had been due to begin in the first week of April. We drove into a near empty carpark at The Royal Marsden Hospital, Sutton, Surrey and when I went in to the hospital to the pharmacy I only saw one patient and he was wearing an oxygen hood and moon suit. The normally bustling hospital was deserted and we know this has had knock on effects and delays in treatment to this day.

All of this evidence over and above the direct impacts of dealing with Covid patients caused Baroness Hallett to question how it could be claimed that the system did not collapse when cancer screening was stopped, for example. How indeed.

Route of transmission – it’s airborne!

One thing that really stands out from the Inquiry testimonies is just how many professional bodies and experts repeatedly raised the alarm about the inadequate infection control guidance in hospitals and how these concerns were disregarded at every step.

This is integrally linked to the debate about how Covid-19 spreads. A key problem was that the World Health Organisation, the UK IPC cell (Infection Prevention cell which produces guidance on infection control in hospitals), and Public Health England which subsequently merged into UKHSA, maintained the line that Covid-19 spreads via droplets. This is captured in this video montage from X (twitter).

Various experts, including Dr Barry Jones of CATA, and Professor Clive Begg told the inquiry that the scientific evidence strongly indicated that the virus was airborne the moment it entered the country. Others, including Professor Catherine Noakes, noted that it quickly became obvious that airborne transmission was happening through evidence from super spreader events and this should have been a red flag. Staff working on the front line also told the inquiry that they strongly suspected airborne transmission early on. For example, Professor Colin McKay testified that as early as April 2020, it was increasingly clear to those on the ground that airborne transmission was taking place.

The reason why the mode of transmission is important to the discussion is that if Covid was ‘only’ transmitted via droplets that fall to the ground or via close contact, fluid resistant masks ie surgical masks – also called baggy-blues are all that is needed to protect staff .

From the start of the pandemic it was deemed from on high that aerosol generating procedures (AGPs) were the exception and required a higher level of PPE – usually FFP3 masks. These procedures are usually, though not always, performed in ICUs. However, as the inquiry progressed it became increasingly unclear whether it was possible to draw a distinction between AGPs and other procedures when dealing with Covid-19 patients. This is well illustrated by the evidence from Dr Ben Warne, who pointed out that the majority of Covid patients presented with a cough and coughing produces many aerosols!

If the virus had been designated as airborne, it is arguable that FFP3 masks would have been advised by the IPC cell (since surgical masks do not protect against aerosols) and there would have been less obsession with hand washing and cleaning which whilst useful for other reasons, offers little protection against an airborne virus.

Also a great deal more attention would have been focused on ventilation as it should have been recognised that the virus can hang in the air for hours, rather like cigarette smoke, and therefore needs to be cleared.

This is perhaps one of the key errors made during the entire pandemic. Some of the evidence offered by key players in public heath England/UKHSA, IPC cell and the chief medical officers at the height of the pandemic illustrates what was going wrong on key issues. Indeed, on occasions the sessions, including from Dr Lisa Richie Deputy Head of the IPC cell , been embarrassing to watch.

The only exception is former health secretary Matt Hancock who on 21 November in response to a question, implied that of course it was obvious that the virus was airborne.It is unfortunate that he did not say this at the time!

Staff working on the front line and patients had to bear the brunt of these mistakes. For example, ambulance workers had to ensure working in poorly ventilated ambulances with inadequate, inappropriate guidance on PPE to protect them from a virus that would go on to kill many ambulance staff.

In her evidence Tracy Nicholls, Chief Executive of the College of Paramedics likened ambulance workers to canaries in a coal mine – see the following video clip from their closing statement.

Finally it is pertinent to note that many witnesses stressed that even if the science had been unclear, given the novel nature of the virus the precautionary principle should have been adopted. In other words rather than arguing that we need to wait for the science to prove that it is airborne we should have applied protective measures until it was proven that the virus was not airborne. When questioned about why this did not happen witnesses from the state machine tended to skirt around the issue and no one gave a satisfactory answer. This is surely a key lesson for the future. The legal counsel for the BMA drew out this point in his closing statement. See below.

Surely one really key lesson for the future is to involve people from a range of disciplines, including those in frontline roles, before IPC guidance is finalised.

The next two sections discuss the key Infection Prevention and Control measures – masks and ventilation.

Infection Control Measures: Masks

The Inquiry heard a great deal of debate about the effectiveness of different types of masks. Many expert witnesses argued that FFP3s should have, and indeed should be, offered to all staff. There is extensive evidence on the effectiveness of FFP3’s and indeed FFP2’s compared to surgical masks and some of this is reviewed in section 3 of my blog on How to Avoid Catching Covid.

Yet a number of people appeared before the inquiry and argued that FFP3’s were not more effective than surgical masks, in part because it was claimed that FFP3s tend to be uncomfortable and staff often don’t wear them correctly. Unfortunately no one has seen the evidence that witnesses quoted to justify this position. Indeed, in her evidence Dr Susan Hopkins Chief Medical Advisor at the UKHSA argued this and was challenged by Baroness Hallett in a famous scene from the inquiry in which Hallett holds up a surgical mask against a FFP3 and challenges Hopkins on the issue.

When questioned, Professor Philip Bamfield, chair of the BMA UK Council disagreed with what Susan Hopkins said and cited evidence from real life hospital settings that FFP3 masks are effective – see the following video clip.

It is also pertinent to note at this point that anaesthetists and intensive care nurses and other working in the highest risk areas where AGPs were being performed (who were wearing FFP3 masks) ended up being less likely to get infected than staff on other wards on a number of measures including infection rates. If FFP3’s were not, as claimed, more effective, why was this the case?

Dame Jenny Harries Head of the UKHSA also argued that FFP3’s were not more effective and went on to claim that Dr Shin had told the inquiry earlier than they were not. Yet when we look at the evidence given by Dr Shin and his colleague Ben Warne we can see that this is not what they said. It is true that there are nuances in what was said but both supported the use of FFP3s for staff treating Covid-19 patients.

Some of this may stem from key figures attempting to cover their tracks given decisions taken in mid March 2020 to restrict access to FFP3’s to ICU staff and others performing aerosol generating procedures, despite the increasing numbers of very sick patients being cared for on general wards.

There are very strong suspicions that the changes were introduced because of a shortage of PPE at the time. But how very much better it would have been if key players had explained the international shortage of PPE at the start of the pandemic, put in place compensating mitigation measures such as ventilation and also promised high quality PPE as soon as available. Instead they have repeatedly attempted to cover their tracks and stuck to their original scripts.

Fit Testing

FFP3 masks are meant to be fit tested to ensure there is no leakage. The inquiry heard a great deal about fit testing and particularly the fact that certain groups were more likely to fail a fit test; in particular women sometimes failed because masks are modelled on the average male face, and some ethnic minority groups were more likely to fail because of the shape of their faces and the presence of facial hair.

I have three key observations on this, Firstly, as a major procurer of PPE it seems incredible that the NHS failed to do more to push manufacturers to produce FFP3 masks for different types of face. Secondly, to then throw up your hands and imply that FFP3s are not suitable for everyone so staff can wear a surgical mask instead is completely inappropriate. There is a world of difference between a non fit tested FFP3 that maybe has relatively minor leakage and a surgical mask that gapes at the sides and top! Thirdly, the inquiry avoided talking about the masks that are used extensively in the rest of Europe and in the US – namely FFP2 masks (offering 95% protection compared with the 99% offered by a FFP3). These are significantly more protective than surgical masks, there are a wide range of shapes and sizes on the market, they are cheap and they don’t need to be fit tested.

Infection Control Measures : Ventilation

The lack of attention to ventilation in hospitals and other health care settings, and a complete failure to educate the public on the importance of cleaning the air, thus removing viruses from it, is one of the key errors made. Whilst the inquiry got bogged down in debates about how small a droplet would have to be to be classified as an aerosol mode of transmission, key player after key player seemed not to grasp, or did not want to admit, how critical clean air is in preventing transmission. In doing this they failed to draw on lessons learnt in the 19th century as explained in the closing statement made by legal counsel to the Scottish bereaved families in the video clip below and as practiced by my late aunt in the first half of the 20th century!

Throughout the inquiry we heard extensive debate about the age of some of the hospital estate and excuses that better ventilation would have to wait for hospital rebuilding and refurbishment programmes, including the building in of modern air filtration systems.

This could of course take decades to achieve. Meanwhile state witnesses seemed to have developed a kind of collective lack of awareness about the potential of HEPA filtration to clean the air and reduce the transmission of infections. Many clinically vulnerable families deploy HEPA filters as explained in my blog – how to avoid catching Covid. They have also been shown to work well in hospital settings as demonstrated by trials including the Addenbrooks trial.

On a positive note, however, some of the key witnesses, including the UKHSA, did in their closing statements concede that ventilation was important and also that representation of a wider range of disciplines in the IPC cell. In response to a question from the CVF lawyer, Sir Chris Whitty also acknowledged that they did not pay sufficient attention to ventilation. This is significant.

It remains to be seen whether the chair is prepared to make any urgent interim findings and recommendations of the type called for by CATA (Covid Airborne Transmission Alliance) and supported by the CVF group and other core participants. Specifically the IPC (Infection Protection and Control) cell guidance needs to be changed and this needs to happen quickly.

Clinically Vulnerable Families (CVF)

A highlight of the inquiry was when Dr Catherine Finnis, CVF’s Deputy Head took the stand – this thread captures the key points made, including: the shielding programme and its limitations; the position of the clinically vulnerable and household members of the CEV and CV who were not shielded; the continuing lack of information on issues such as routes of transmission, types of masks and other protections (and the fact that the CVF group are having to fill the information gaps); the difficulties of accessing healthcare safely post summer 2022, and evidence of members avoiding appointments or switching to private providers for safety reasons; the growing problem of mask abuse; and the issue of do not attempt resuscitation orders.

All of the key points raised by the clinically vulnerable families group were reiterated in the closing statement made by CVF’s counsel Adam Wagner. A thread of this can be found here.

There were many differing experiences of the shielding programme and indeed lockdown, and the pandemic more generally within the CVF group. The testimony from CVF member Lesley Moore provides insight into her experiences of caring for her CEV adopted son who suffers from severe cerebral palsy, is nil by mouth and usually requires two carers at any one time except during periods when Lesley is caring for him. From March 2020 his day care centre closed, carers were not allowed to visit and she was left on her own to care for her son without any support 24/7 for 18 months. The toll this took on Lesley’s physical and mental wellbeing (because she didn’t feel the government cared) was considerable.

Shielding

Millions of CEV people were formally shielded during the early peaks of the pandemic and were in effect ordered to stay at home and keep two meters apart from others in their household. In return they received priority supermarket food delivery slots, food parcels, and a number of pass porting rights such a right to work at home or receive statutory sick pay.

There were many potential benefits to the programme, particularly the prioritisation of access to food delivery slots and a right to work at home. However, there were also a number of drawbacks, including the loneliness sometimes caused by requiring that people did not go outside, the practicalities of living arrangements where the shielded person lived in a household with others, including children, as most shielded people did. Indeed failure to give pass porting rights to people who lived with a shielded person arguably lessened the effectiveness of the programme. Other problems included the stark divide where the CEV (clinically extremely vulnerable) were shielded, and the CV (clinically vulnerable) were not, despite the somewhat arbitrary cut off between these two groups of people.

Although there was some research commissioned to look at the effectiveness of the programme, it was limited in nature. One of these projects was undertaken by Professor Helen Snooks took the stand at the Inquiry to answer questions about her research. Her overall conclusion is that the programme made no difference to the chances of catching Covid or deaths, and overall, given the costs and the negative impacts of shielding she could not recommend it in future.

However, when we dig underneath this it emerges that this ‘no impact’ finding is to a large part explained by the fact that shielders were more likely to have to attend hospitals and healthcare settings and were more likely to get infected in these settings as a result. Therefore, even though she was reluctant to answer a question about the desirability of improving IPC in healthcare, surely the answer is to improve infection control in hospitals to the benefit of CEV people as well as shielding them at home. During questions from the CVF lawyer, Snooks also acknowledged that the passporting aspects of shielding, including food parcels, priority shopping slots, entitlement to statutory sick pay, a means of explaining their risks to employers etc were all positive and helpful aspects of the programme that she did not consider.

In sum, I tend to agree with Professor Whitty who has previously commented that it is not possible to know how effective the shielding programme was because it took place at the same time as general lockdown and it has been impossible to undertake a randomised control trial.

During her evidence session Catherine Finnis also stressed that in her assessment which also reflects the views of many people, any future shielding programme should place more emphasis on empowering people with the information needed and means to protect themselves eg information on which masks to wear, how to clean the air with HEPA filters etc rather than dictating how they should live their lives and run their households.

One of the other key criticisms made by the former shielded was the cliff edge approach to the ending of shielding with no continuing support or advice provided. For example, the pausing of shielding at the end of July 2020 happened when rates of infection had started to creep up, ‘eat out to help out’ was introduced and there were no vaccines. Many people liken it to being thrown to the wolves.

The process could have been much better and safer had those affected been consulted about shielding, including the ending of shielding. However, when asked by the CVF lawyer whether he had considered carrying out a consultation with those impacted by the decision, Sir Sajid Javid, the Cabinet Minister in charge of the policy at the time when shielding was finally ended said he had not because the decision to start and end the policy was based on ‘scientific and medical fact’ – see video below.

This tendency to ignore the impacts on people of the measures introduced, including shielding, is surely one of the key lessons for the future. If policy makers ignore people, their attitudes and the underlying drivers of behaviours, policies will tend to have unintended consequences and be sub optimal. After all to comply with the guidance of keeping two meters apart from other household members (who were not covered by shielding arrangements) sometimes led people to move into tents or borrowed caravans in the garden. Was this what policy makers intended? How else were people meant to comply with dictates from on high? But alas it seems that those responsible for policy do not want to know how people implemented it in practice.

Safety in Healthcare

As we can see from the poster, the vast majority of Clinically Vulnerable people and their families feel unsafe attending healthcare settings primarily because of the limited ventilation and the lack of mask mandates. In the next clip CVF member Aaron who has suffered from severe asthma forever explains some of the issues.

Moreover, monitoring by the CVF group reveals that people perceive that healthcare has become increasingly unsafe given the lack of ventilation and following the complete withdrawal of mask mandates, and the decreasing numbers of staff and patients who wear a mask. In the following video CVF member Sarah explains how she felt increasingly unsafe as IPC measures worsened.

During her evidence to the Inquiry, Dr Catherine Finnis explained how many CVF had been left to either avoid seeking healthcare advice and treatment or going private. Indeed, I myself have sought out private treatment because of the dangers of entering an NHS setting.

In the above clip Catherine explains the juxtaposition between current NHS guidance to CEV people on how to keep themselves safe and the reality of the lack of IPC procedures in many/most healthcare settings at this moment in time.

In their evidence statement CVF called for a return of face masks for staff and patients in all high risk settings.

Do Not Attempt Clinical Resuscitation Orders DNACPRs

The inquiry heard extensive claims made by the Bereaved Families groups and others about the inappropriate use of Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation orders. These notices are in normal times usually taken as meaning that if your heart or breathing stops your healthcare team will not attempt to restart it. They are meant to be placed after careful consultation with the patient, their relatives and healthcare team as appropriate and are recorded on a special form which is a different colour and placed on medical records.

However, the Bereaved Families Groups and others presented extensive evidence about DNACPR notices being placed without any consultation with relatives or indeed patients who survived to recount their experiences. There is also considerable disquiet that DNACPR was sometimes treated as a ‘do not treat’ order.

Particular concerns were raised across different evidence sessions about blanket DNACPRs being placed depending on the characteristics of groups of patients. Particular disquiet was expressed about their use, as a matter of routine, in treating certain disabled people where the underlying disability was stable – people and children with Downs Syndrome, for example.

There is also disquiet within the Clinically Vulnerable Families community, particularly as a number of individuals have since discovered DNACPR notices, that they did not agree to, on their medical records.

However, when questioned all of the state witnesses were adamant that blanket DNACPR notices were never placed on categories of people.

The Clinically Vulnerable Families group is calling for a review of all DNACPR notices put in place from the start of the pandemic and a formal review of the notes of all people who were previously shielded. This is supported by several other groups including Bereaved Families for Justice group.

The CVF group are also calling for revisions to be made to the Equalities Act in order that clinical vulnerability is recognised as a specific form of inequality.

Data

It was evident from the evidence presented that lack of data was a major problem. This sometimes stemmed from a failure to collect data in the first place, difficulties in linking different data systems, badly designed information systems, and a failure to provide all the data requested. The lack of capacity to analyse data was also in evidence and as we witnessed, near raw data sometimes throws up far more questions than useful answers.

I have already commented on the problems of measuring overall bed capacity in the system and would strongly support a common agreed measure to inform policy makers and others about whether capacity was being breached.

The organisations representing black and ethnic minority health care workers and migrant workers repeatedly questioned witnesses about missing ethnic coding from key data. This effectively means that although we know that BME healthcare workers were more likely to catch covid, and more likely to die, we do not know the exact extent of this.

There are also significant data problems with trying to estimate the number of nosocomial infections (hospital acquired infections) and subsequent death rates from Covid-19 caught whilst being treated for something else.

Another key area when the available data raises more questions than answers is the issue of whether the clinically vulnerable and CEV were systematically being denied access to ICU care. The data is suggestive -but we can’t definitely conclude this because of lack of the right data and analysis.

Data to support shielding was also an issue which meant that some people who should have been shielded did not receive any notification or were only informed in late April 2020 and some fell through the cracks completely.

Clearly improvements are necessary across the board to ensure that the data collected is the right data, is accurate and there is analysis capacity to make sense of it.

We also need more evidence on the impacts of measures on people, as illustrated in the reference above to the lack of consultation with those impacted about aspects of the shielding programme.

The Nature of Evidence

Throughout the hearings we heard a great deal of debate about evidence and experts on a range of issues, including the imperfections, evolutionary nature and interpretation of the evidence. There are two key points I wish to draw out here.

Firstly, the hearings on module 3, as well as the previous module 2 on political decision making, exposed what has been dudded as ‘groupthink’ at the centre of government. This happens where officials and experts, often handpicked to sit on committees are generally of broadly similar persuasions on key issues. In effect it seems that those expressing different interpretations and conclusions were sometimes – perhaps even often – labeled as ‘outliers’ with the consequence that their conclusions were never seriously considered and certainly never reached Ministerial eyes. Moreover, even when their voices were heard on committees the overall emphasis was on reaching consensus. Indeed, several witnesses to the module 2 hearings told the inquiry that minutes of meetings did not reflect the full range of discussion, but focused on the overall majority ‘consensus’. The overall secrecy surrounding the membership of and minutes of committees facilitated the lack of exposure of key issues and controversies.

This had very serious consequences – for example on the issue of how Covid-19 spreads. A number of witnesses repeatedly raised concerns from the start that Covid-19 was airborne and they have subsequently been proved to be correct. Yet these people, including Professor Beggs and Dr Jones were simply not listened to. This is key and cannot be allowed to happen in the future. Yet many of us who previously worked in Whitehall recognise it and the clear need for change.

The second issue is methodologies, and in particular the prominence given to Randomised Control Trials (RCTs) as the ‘gold standard’. The reality is that assessing the impact of measures deployed in community settings such as hospitals cannot rely on evidence drawn from RCTs alone. The real world is complex and it is often difficult to undertake a genuine trail of the type used to test the effectiveness of drugs for example. Also policy makers usually need to understand why things are having an impact or not, including any unintended consequences, but RCT’s cannot do this.

Policy makers need to be alive to these issues when assessing evidence and it is therefore very frustrating that despite all of the evidence presented about the impacts of different types of masks in real world settings that bodies such as UKHSA cling onto the line that there is insufficient evidence (ie no RCT evidence) to recommend that staff wear well fitting masks.

I will return to the issue of evidence in a subsequent blog as it deserves more space than I have been able to give it here.

Long Covid

Evidence from March 2024 estimated that there were over two million people suffering from Long Covid in the UK – and this represented an increase in the proportion and number of people suffering compared with March 2023.

Long Covid is a complex condition as explained in my blog on the subject.

The inquiry heard extensive evidence that staff working in healthcare were more likely to go on to acquire Long Covid than the general public, but again data on this is scarce. What is clear is that staff damaged by Long Covid have not and are not being provided with the support they need to help with their recovery and facilitate a return to work.

The inquiry heard evidence from Dr Nicola Campbell who acquired long covid at the start of the pandemic. She described her symptoms and the impact of the over exertions and subsequent crashes commonly experienced by LC sufferers.

In their evidence Professors Chris Brightling and Rachel Evans reminded us of who is more likely to get long covid : – women, people with pre existing conditions, middle aged and lower socio economic groups. This underlines the importance of long covid as an issue for the clinically vulnerable many of whom suffer from long covid if they manage to survive a covid infection. As Brightling and Evans note, CV people are more likely to get a severe form of Long Covid.

There is now very extensive evidence that Covid-19 is not a simple respiratory virus, and can, and does, damage over 200 organs, including the heart, lung and brain and can also lead to changes in the blood and clotting. It is not surprising therefore that Covid-19 often makes underlying conditions worse, sometimes considerably worse.

(Although not called to the Inquiry to talk specifically about long covid,) Professor Charlotte Summers talked about how Covid-19 can impact on multiple organs in the body and how this understanding evolved over time – see the following video clip. And we now have extensive hard evidence that, far from developing some kind of herd immunity, the more Covid infections you have had the greater the chance of developing long covid and the greater the chance of being repeatedly infected. Also, Covid may actually lower your resistance to other illnesses and infections which is one of key reasons why we are now seeing such a hike in illness.

Many long covid sufferers find one of the key challenges is to get medical practitioners and others to believe them when they talk about their symptoms and the impact on their lives.

Long Covid clinics are part of the solution for people with medium-severe symptoms and Professors Brightling and Evans reminded the inquiry about the key benefits of these clinics which are multi-disciplinary and aim to treat the multiple symptoms of sufferers under one roof. Clinics also provide a critical mass of patients and experts to enable learning about the complex subject of long covid and act as a basis for gathering data and research evidence. Professor Brightling went on to highlight that these clinics are now being wound down as responsibility passes to local providers supposedly geared to ‘meeting local needs’. In the words of Brightling this means that :

‘long covid patients’ voices will fall silent as support is inadequate and clinics evaporate, the condition will become invisible for being dismissed and ignored. We are at a tipping point he warned‘.

It also became evident during the course of the inquiry that some countries – most notably Wales – do not have specialist clinics but rely on GPs. When pressed, several witnesses put this down to the geography of Wales. However, others see this as a red herring as Wales is more densely populated that some other areas and countries, most notably Scotland.

In her closing statement counsel for the Long Covid groups drew attention to the lack of data on the extent of Long Covid. Indeed, the termination of the ONS infection survey makes this bad situation even worse as this survey was the only source of national data on the number of people suffering from self reported long covid. This is despite the fact that the estimated number of people suffering from long covid went up between April 2023 and April 2024 when data was last published, including an alarming rise in the number of children suffering from long covid. Indeed, I am not aware of any other area of public policy where data collection appears to have been deliberately stopped following the release of data showing that the problem under scrutiny is getting worse.

Concluding Comments

This module of the Inquiry has proved to be eye opening in a number of ways but it has also given a voice to a number of groups which the barrister representing the Long Covid groups likened to ‘the survivors’.

For all grassroots groups this inquiry has involved small groups of volunteers pouring over reams of paperwork, briefing legal teams, keeping a close eye on all the proceedings and lobbying the press and raising the profile via social media platforms. We hope that our efforts pay off.

One striking thing about the hearings just how obvious various witnesses have been in seeking to justify their own actions at the start of and throughout the pandemic rather than own up to mistakes and help seek solutions for the future. It is hoped that the chair of the inquiry will be able to see through all this in drawing up her conclusions and recommendations. This includes the evidence from the current Permanent Secretary at the Dept for Health and Social Care, Sir Chris Wormald whose evidence can, at best, be described as somewhat evasive. Indeed, Counsel for the Bereaved Families for Justice summed it up as ‘word salad’. Sir Chris has of course very recently been appointed as the new Cabinet Secretary to the almost disbelief of many people who watched his testimony live, including myself. It remains to be seen whether this appointment proves to be a barrier to implementing the recommendations from the inquiry.

Of course, it is not inevitable that the findings and recommendations of the inquiry will be implemented. Indeed recommendations from far too many inquiries are left to sit on bookshelves. In the words of Baroness Hallett, it will be down to the groups who this inquiry has afforded a voice to ensure that this one does not gather dust.

I need to stress here that this is not a comprehensive account of module 3. Due to pressures of space I have missed out full discussion of inequalities, communications, the ‘hierachy of control’ of control approach, the role of pharmacists, and much more. I hope to return to some of these topics in subsequent blogs.

Next month the Inquiry moves on to hear evidence on Module 4 on vaccines and therapeutics, followed by modules on procurement, test and trace, care homes, children and young people, the economy and the impacts on society.

Gillian Smith December 2024

NB I am an active member of the Clinically Vulnerable Families CVF group and am closely involved in supporting our role on the inquiry. However, as is pertinent to all blogs on this website, and as highlighted on the homepage, what I write here is not an ‘official’ view and does not necessarily reflect our policy on all matters.

Further reading/ listening

Jim Reeds weekly podcasts provide a good overview of what happened on each week of the Inquiry hearings

All of the hearings can be found on the Covid Inquiry YouTube channel – it is particularly worth investing time in watching the evidence presented by Professor Kevin Fong in its entirety.

All of the hearing transcripts and documents can be found on the Inquiry website.

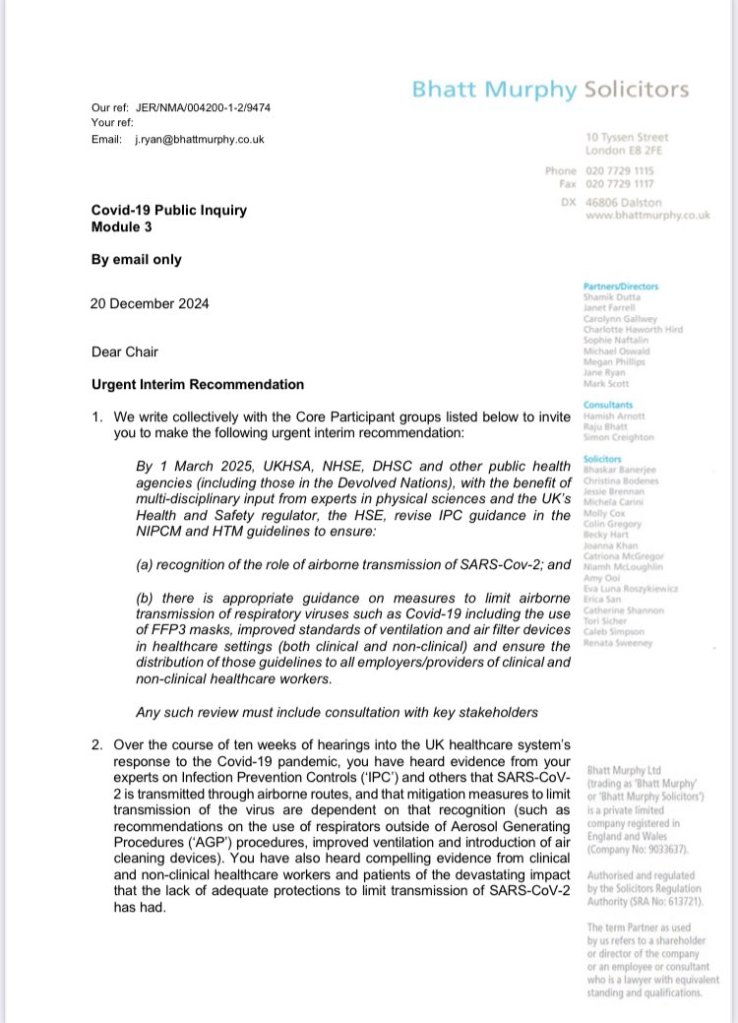

Update – 20 December

Several of the core participants to module 3, including the Clinically Vulnerable Families group have today co-signed a letter to the inquiry chair calling for changes to the IPC guidance and other measures. This is reproduced below. Also see my blog on

Leave a comment