On 9 September public hearings resume with hearings on module 3 on healthcare systems. This module will cover the following very pertinent issues:

This module will consider the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare systems in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. This will include consideration of the healthcare consequences of how the governments and the public responded to the pandemic. It will examine the capacity of healthcare systems to respond to a pandemic and how this evolved during the Covid-19 pandemic. It will consider the primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare sectors and services and people’s experience of healthcare during the pandemic, including through illustrative accounts. It will also examine healthcare-related inequalities (such as in relation to death rates, PPE and oximeters), with further detailed consideration in a separate designated module.

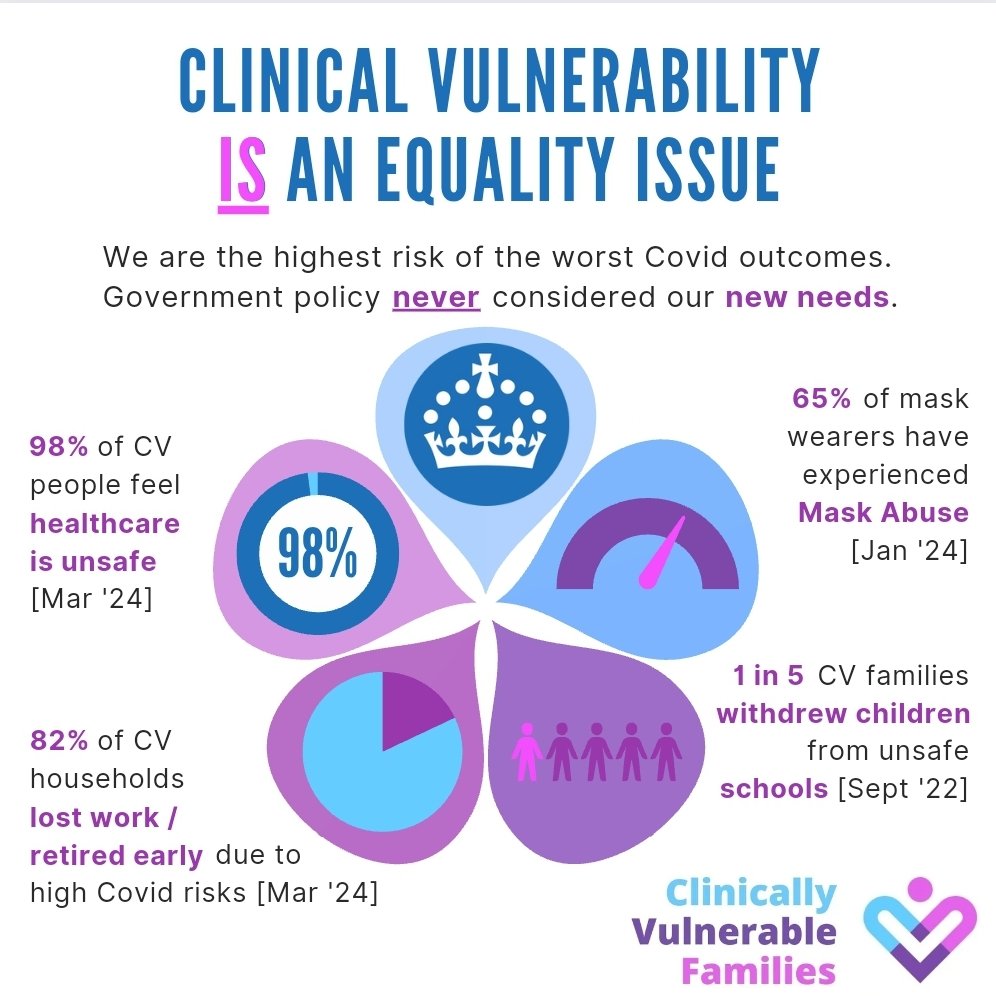

This is the first module in which the Clinically Vulnerable Families group has been granted core participant status. This means a right to legal representation, access to all documents electronically, and the right to suggest areas of questions and to question witnesses.

It is hoped that this will help to correct some of the problems that occurred during modules 1 and 2 due to the lack of input from the clinically vulnerable and their families given the specific challenges that we face, in accessing healthcare, for example.

The report of the key module 2 on political decision making during the pandemic will be published in the new year – hopefully earlier rather than later, whereas module 1 was published over the summer.

Module 1 report

On Thursday 18 July 2024 the report of the first module of the Inquiry into the resilience and preparedness of the UK for the pandemic was published. This makes grim reading and lays bare the failings in the run up to the start of the pandemic in 2020. This is a very important report because as Baroness Hallett has made clear in a short video clip, ‘as the expert evidence makes clear, it’s not a question of it another pandemic will strike, but when’.

The report contains a summary of the key points and Duncan Robertson has also produced a helpful thread.

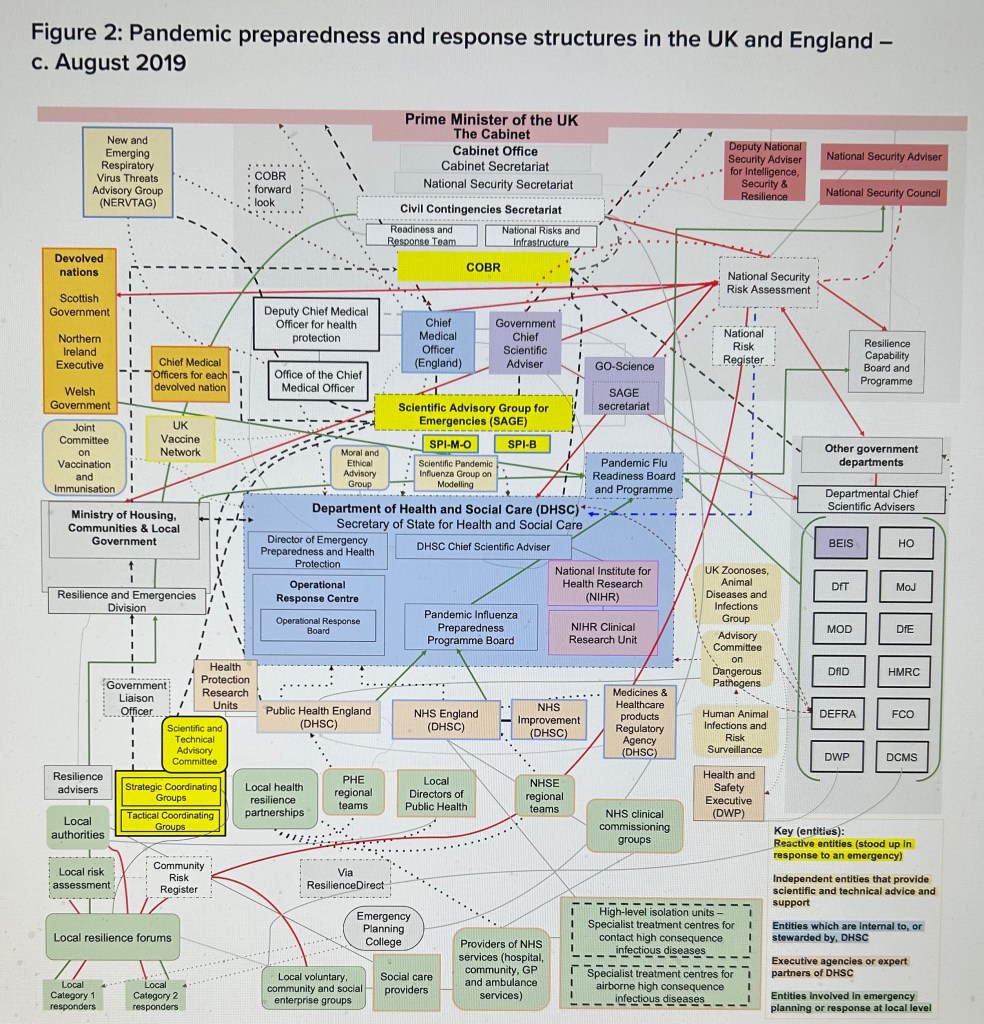

The system of building preparedness for the pandemic was found to suffer from a number of significant flaws, including the following:

- Despite planning for an influenza (also known as flu) outbreak, our preparedness and resilience was not adequate for the global pandemic that occurred (this is despite the fact that coronaviruses in Asia and the Middle East in the preceding years meant another coronavirus outbreak at a pandemic scale was foreseeable.)

- Emergency planning was complicated by the many institutions and structures involved;

- The approach to risk assessment was flawed, resulting in inadequate planning to manage and prevent risks, and respond to them effectively;

- The UK government’s outdated pandemic strategy, developed in 2011, was not flexible enough to adapt;

- Emergency planning failed to put enough consideration into existing health and social inequalities and local authorities and volunteers were not adequately engaged;

- There was a failure to fully learn from past civil emergency exercises and outbreaks of disease;

- There was a lack of attention to the systems that would help test, trace, and isolate. Policy documents were outdated, involved complicated rules and procedures which can cause long delays, were full of jargon and were overly complex;

- Ministers, who are often without specialised training in civil contingencies, did not receive a broad enough range of scientific advice and often failed to challenge the advice they did get;

- Advisers lacked freedom and autonomy to express differing opinions, which led to a lack of diverse perspectives. Their advice was often undermined by “groupthink” – a phenomenon by which people in a group tend to think about the same things in the same way. This is something that anyone who has ever worked in the civil service will recognise.

Although the report does not major on it, it is very clear that in the preceding year or so, the entire government system was in chaos characterised by significant ministerial and political churn, a general election and a civil service focused on preparing for a no deal Brexit.

The key recommendations are:

- A radical simplification of the civil emergency preparedness and resilience systems. This includes rationalising and streamlining the current bureaucracy and providing better and simpler Ministerial and official structures and leadership;

- A new approach to risk assessment that provides for a better and more comprehensive evaluation of a wider range of actual risks;

- Better systems of data collection and sharing in advance of future pandemics, and the commissioning of a wider range of research projects;

- A new UK-wide approach to the development of strategy, which learns lessons from the past, and from regular civil emergency exercises, and takes proper account of existing inequalities and vulnerabilities;

- Holding a UK-wide pandemic response exercise at least every three years and publishing the outcome;

- Bringing in external expertise from outside government and the Civil Service to challenge and guard against the known problem of groupthink;

- Publication of regular reports on the system of civil emergency preparedness and resilience;

- Lastly and most importantly, the creation of a single, independent statutory body responsible for whole system preparedness and response. It will consult widely, for example with experts in the field of preparedness and resilience, and the voluntary, community and social sector, and provide strategic advice to government and make recommendations.

The report received a fair amount of media coverage in the UK, though this was probably limited by other competing big news stories at the time, including the Kings Speech setting out the key priorities for the new Labour governments legislative programme, and the on-going saga of whether or not Joe Biden would step down as a candidate in the forthcoming US election.

The coverage in the Guardian on the day of publication made some of the key points followed up the next day with a report elaborating on why the UK is in a worse state than before the pandemic, particularly in terms of ingrained inequalities and the state of the public health system.

In Christina Pagel’s assessment it was not necessarily that the government planned for the wrong pandemic, but that it planned for failure:

“The strategy was beset by major flaws, which were there for everyone to see. Instead of taking the risk assessment as a prediction of what could happen and then recommending steps to prevent or limit the impact, it proceeded on the basis that the outcome was inevitable.” Pagel see ref above

Christina also makes the point that we need to be more explicit about our core values in an emergency situation. Core values means things such as how lives are valued (who decides how many deaths are acceptable), and whose, or how trade-offs between the burden and costs of policy measures and potential lives saved are evaluated.

She goes on to argue that social research /deliberative research is needed to understand public priorities and get buy-in during an emergency. Indeed, the chair of the inquiry does recommend that the public be “consulted, engaged with, and informed” about how governments intend to respond in the event of an emergency. And there should be ‘concrete plans to elicit, codify, and communicate our nation’s values and priorities in future emergencies’. ‘These would then underpin a more transparent and effective process for preventing, mitigating, and dealing with future emergencies’.

More generally Pagel argues that pandemic planning should not be something that is considered in a separate box. It should be part and parcel of everyday policy making and practice on a range of issues and planning for an emergency should be at the forefront of everyone’s minds throughout.

Two Key Omissions

I think there are at least two key problems with the way in which the inquiry has been set up.

Firstly, the timeframe. The inquiry is only considering evidence up to mid 2022 after the final pandemic restrictions were removed. This is a key problem for the clinically vulnerable and their families and others who recognise the dangers from covid infections. Whilst the height of the pandemic was clearly challenging for us, many of the problems that we face, and some would argue most of the problems, occurred after the restrictions were dismantled.

The inquiry is essentially missing the era that we are now in where most people appear not to care whether they get infected, and are often indifferent to or even hostile to those who need to take precautions – see my blog on mask abuse, for example. In addition there are next to no mitigations in healthcare and education, and navigating issues around work are becoming increasingly difficult given that some employers operate with a blind belief that physical presence in the workplace is best, even when people spend all their time looking at a computer screens.

A second key omission is the failure to explicitly seek out learning from other countries. This is despite the fact that the UK has the highest death rate in Europe and the second highest in the world, spent longer in lockdown than anywhere else and experienced more disruption to healthcare systems. Why is the inquiry not explicitly asking questions such as why did South Korea have so few deaths and no lockdowns? Some would say it would have been impossible to transport lessons from the Far East to Europe, but does the Inquiry not need to be critically examining this question? Many European Countries with similar cultures and systems also performed significantly better than us and it would be worthwhile to look at experiences from countries such as Germany, for example.

Concluding Comments

Finally, it is important to ask ourselves the question – what is the point of public inquiries given all the resources and hard work that goes into them, not just work funded by the state, but also the long hours committed by the voluntary organisations that provide evidence to inquiries? Christina Pagel has asked herself this question. The key point is that the recommendations of inquiries need to be implemented. Sadly too many recommendations are left to sit gathering dust on the shelf.

It is abundantly clear that the UK needs a far stronger system of ensuring that recommendations are implemented in a timely way, particularly taking account of the need to implement emergency pandemic planning into everyday practice. A number of other countries have mechanisms in place for achieving this and we need to learn from them without delay.

It is also hoped that the messages from the clinically vulnerable group will resonate with the inquiry and the lessons for current policy will be reflected in the interim and final reports of the inquiry.

Gillian Smith 5 September 2024

Leave a comment