The UK Treasury is running a public consultation about the forthcoming budget and government spending priorities. I have taken the opportunity to submit a piece on the case for extending entitlement to free Covid-19 boosters and the need to address the high rates of Covid-19 that are continuing to cause disruption across the UK all year round.

I encourage you to do the same. Making a submission is easy and I have pasted in a link for doing this at the end of this blog.

Submission

The Joint Committee on Vaccination proposes restricting the Autumn booster jab programme to : adults aged 65 years and over, residents in care homes for older adults; and persons aged 6 months to 64 years in a clinical risk group. This will further restrict access to the vaccine and denies it to household contacts of people with immunosuppression and unpaid carers, for example. This places us in an impossible position of trying to protect our loved ones without the benefit of a vaccine boost.

The JCVI appear to fail to take account of how Covid spreads. People are not isolated atoms, they need to interact with each other – for example, with health care staff, carers, family, friends and people in their households. It is therefore inappropriate to devise a vaccination strategy as though people are individual atoms. Their household contacts need to be factored into the vaccination strategy.

The underlying assumption behind this restrictive approach is cost effectiveness based on the risk of hospitalisation and death from Covid-19. It is assumed that vaccines are only cost effective when they prevent severe disease and hospitalisation in the immediate aftermath of a Covid-19 infection. The JCVI have failed to publish their underlying analysis for this and simply say ‘it will be published in due course’. As far as we can judge, given the lack of access to the detail, this analysis is flawed. A significant critique of the proposals is provided by Professor Sheena Cruickshank and I commend this to you.

The first assumption underpinning the JCVI analysis is that vaccines have limited impact in preventing disease and transmission between individuals.

It is true that the extent to which vaccines prevent people from catching Covid and how long that protection lasts for is still open to debate between researchers. We do not have enough evidence and the answer will vary between people (depending on their underlying health and immunity), and different strains of the virus. We know that the Covid-19 virus is evolving all the time and the rate at which it is evolving is probably accelerating. This runs the risk that vaccines will be sub optimal in tackling strains of Covid-19 in circulation by the time they are administered into people’s arms. The fact that Covid-19 is not a stable, seasonal illness like influenza (and many scientists say it may never be) further fuels the difficulties.

Nevertheless, there is broad consensus amongst scientists that whilst peak protection may only last a few weeks, the vaccine does help to prevent you from catching Covid and passing it on to someone else for longer, and continues to be helpful as people don’t tend to go back to having zero protection.

Given the uncertainty around the evidence surely it is better to aim for vaccination programmes with the latest/better vaccines targeted at the right point in time than to give up on the idea that vaccines prevent transmission? This is what the World Health Organisation think is best as outlined in their statement of 6 August.

The second key assumption in the JCVI analysis is that vaccines have little impact in preventing post covid conditions (Long Covid).

This statement is deeply flawed. It implies that long covid is declining. The opposite is the case as revealed by ONS data on Long Covid published in April 2024. It is true that one is less likely to get long covid per infection with the omicron variants than earlier forms of the virus as the JCVI say, but the point is that omicron spreads far more easily to a greater number of people – particularly given the lack of public health measures to contain the spread of Covid –therefore resulting in more covid cases and more long covid cases.

An increasing amount of research is coming on stream on long covid and its potential causes including a recent excellent review by Professor Trisha Greenhalgh. This underlies the point that Long Covid is a complex phenomenon that is not fully understood.

An increasing number of studies demonstrate that vaccination reduces the onset of various long covid symptoms including cardiovascular disease, Kidney injury, liver and pancreatic disease, and brain injury to name a few. A recent study from Spain estimates that vaccination has a consistent impact on reducing the chance of developing long covid by up to 52%. And a recent very large scale study found people who received the vaccine generally saw lower risks of overall arterial and venous thrombotic events. The authors conclude:

“These findings, in conjunction with the long-term higher risk of severe cardiovascular and other complications associated with COVID-19, offer compelling evidence supporting the net cardiovascular benefit of COVID vaccination,”

Poor mental health is also often associated with Covid and a recent paper found that amongst patients hospitalised with Covid-19 the incidence of depression, post traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, addiction, self harm and suicide was lower in patients who were vaccinated compared to those who were not. The authors conclude:

‘The findings support the recommendation of COVID-19 vaccination in the general population and particularly among those with mental illness, who may be at higher risk of both SARS-CoV-2 infection and adverse outcomes following COVID-19.”

In many ways the JCVI may be posing the wrong question given the ambiguity around the labels used. They should be asking – what are the after-effects of Covid-19 on the body and what are the cost implications of this including on hospitalisations and deaths from diseases caused by Covid-19, but also the range of economic impacts discussed below.

The range of illnesses caused by Covid-19 is wider than what is sometimes thought of as Long Covid. We know that Covid-19 can cause 200 different illnesses across different parts of the body. Also see a recent compendium of evidence.

Given the mounting evidence on the impacts of Covid-19 on the body, and the potential costs of this to the NHS, the economy and society, it is important to provide people with as much protection as possible with up- to- date vaccines combined with other measures, including clean air and good quality masks. It is completely inappropriate to invent and hide behind the straw man that we cannot conclusively prove that vaccination reduces all kinds of post covid conditions. The JCVI and UKHSA know full well that it is methodologically difficult to conclusively prove a link given the range of variables (other than vaccination status) in play and that research on this is in its relative infancy. Therefore it is surely better to take a more cautious approach and extend the entitlement to free vaccines as the USA are doing this Autumn.

This is particularly important given recently published evidence showing that long covid is more prevalent in deprived areas, particularly in the North of England. If the government is serious about tackling inequalities between different parts of the country it is crucial to take into account the stark differences in the risks of developing Long Covid and tackle them by reducing the spread of Covid-19.

Wider Economic Impacts

a) Prevention of the high levels of withdrawal from the labour market due to ill health, particularly amongst middle aged staff

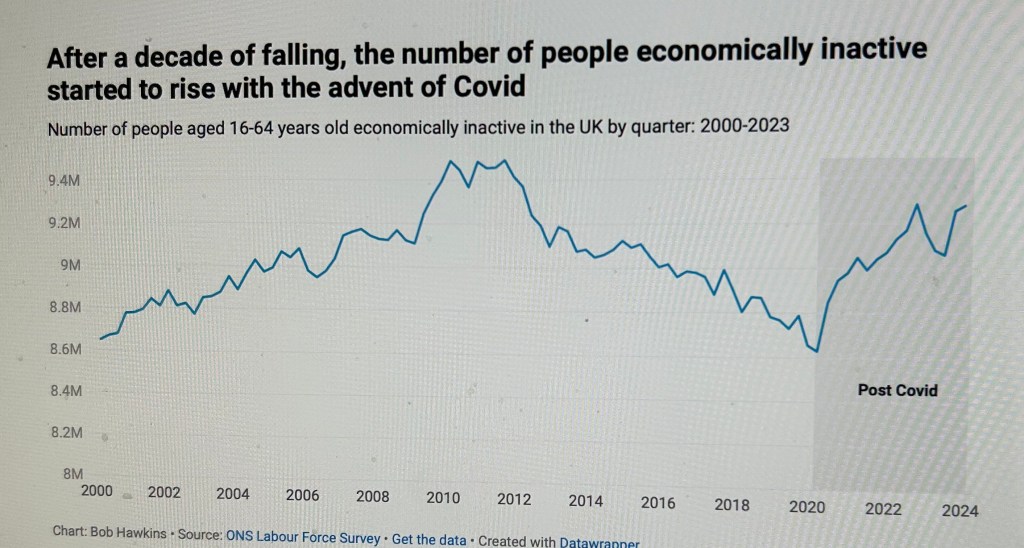

The number of economically inactive working age people has continued to rise since the start of the pandemic. Moreover, the dip observed in early summer 2023 mirrors the fall in the number of Covid cases during that period before it started to rise again as Covid cases took off again.

Apart from students, those aged 50 -64 are by far the largest economically inactive group. And this is the group most impacted by long Covid according to ONS analysis. Moreover, long term sickness has moved from being the third more important reason for leaving the labour market (in 2018) to the most important reason by December 2023 when over 30% identified long term sickness as the main reason for leaving the labour market. And analysis of data on the 50 -64 age group reveals that being sick, injured or disabled was the main reason given for economic inactivity.

As you will be aware, economic inactivity is very costly to the economy. It directly shrinks the supply of labour and hence the economy’s potential to grow. A 2023 study from Oxera estimated that the economic cost of lost output due to sickness among working age people to be between £148 and £190 billion p.a. with between £115billion and £148 billion of this occurring due to working age ill health which prevents people from working.

In addition, Oxera estimate that it costs the NHS an extra £10 billion to treat conditions which affect the ability to work. Also £40 – £51 billion due to lost national insurance and tax revenues, and £16 billion in social security payments to people prevented from working due to health conditions.

Clearly not all of this ill health will be due to long covid, but a very significant proportion of it will be, even if sufferers do not recognise that Covid-19 is at the root of their health problems. This underlines the very strong economic case for taking steps to avoid further growth in the prevalence of long covid and wider ill health associated with Covid-19.

b) reduced time spent off sick by employees and greater employee productivity whilst at work if they are no longer struggling into work sick

The latest available government data on sickness absence from 2022 suggests that the percentage of working hours lost because of sickness and injury rose to 2.6% in 2022 which is the highest since 2004 when it was 2.7%. And an estimated 185.6 million working days were lost because of sickness or injury. The Oxera study estimates that the cost of lost output due to sickness absence to be between £32 billion and £41 billion.

These are not insignificant costs and are likely to be an underestimate of the true scale of sickness related costs due to staff working whilst ill and being less productive as a result. In many sectors of the economy job insecurity and an increasing expectation that staff will come to work when ill, coupled with a general increased emphasis on ‘presentism’ may be dampening down economic performance when staff are underperforming whilst at work. Indeed, a recent study reported in the Guardian found the problem to be costly in the same way as sickness absence itself. The Institute of Public Policy research estimated that the ‘hidden cost of rising workplace sickness in the UK has increased to more than £100bn a year, largely caused by a loss of productivity amid “staggering” levels of presenteeism’.It reported that employees now lose the equivalent of 44 days’ productivity on average due to working through sickness, up from 35 days in 2018, and lose a further 6.7 days taking sick leave, up from 3.7 days in 2018.

c. In addition to the labour market costs of Covid/long covid discussed above there are a range of other costs some of which I list below.

- increased likelihood of employees needing to take time off work to look after others

- increased likelihood of informal carers becoming ill and increasing the burden on the care system through having to take over the care of the adults and children that carers look after;

- Generally lower levels of wellbeing and health across the population leading to less consumer spending and participation in leisure activities, including eating out.

- Allowing Covid-19 to spread and failing to offer free vaccines creates a very dangerous situation for clinically vulnerable people and their households. We are far less likely to spend money on leisure activities, including eating out. This will have a significant impact on the wider economy.

The NHS

Since the start of the pandemic pressures on the NHS have increased considerably because of the resources taken up in treating Covid and related illnesses and resulting delays in treatment for other illnesses and patients becoming more difficult and costly to treat.

The fact that a significant proportion of Covid infections are caught because of inadequate infection controls in hospitals and healthcare settings is further reinforcing the pressures on the NHS. Staff illness is also a significant factor. A recent piece in the Nursing Times suggests that as many as 40% of nurses reported having had Covid in summer 2024 and a worrying 21% of these reported going into work when sick which will only serve to fuel the spread of Covid.

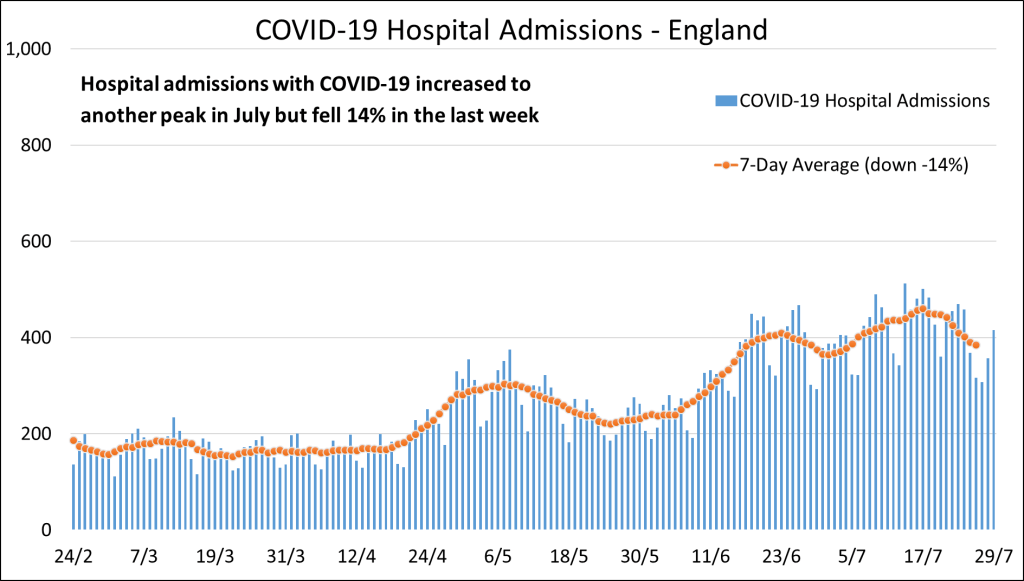

Waiting lists for treatment have almost doubled since the start of the pandemic , waiting times in A and E have soared and it has become significantly harder to get a timely GP appointment. The fact is that the NHS is now, in summer 2024, still being disrupted by Covid all year round. This is in contrast to flu which tends to impact on the NHS for a few weeks in winter.

Hospital admissions with covid this summer are almost double the numbers seen last year.

And this is only the tip of the iceberg of the level of Covid that the NHS is being required to manage in the community. Moreover, in the Nursing Times article cited above, 6 in 10 (61%) said they were worried about how Covid-19 was currently impacting health and social care services and a bigger proportion – 77% – said they were concerned about how Covid-19 will affect services this coming winter, when pressures generally tend to be higher.

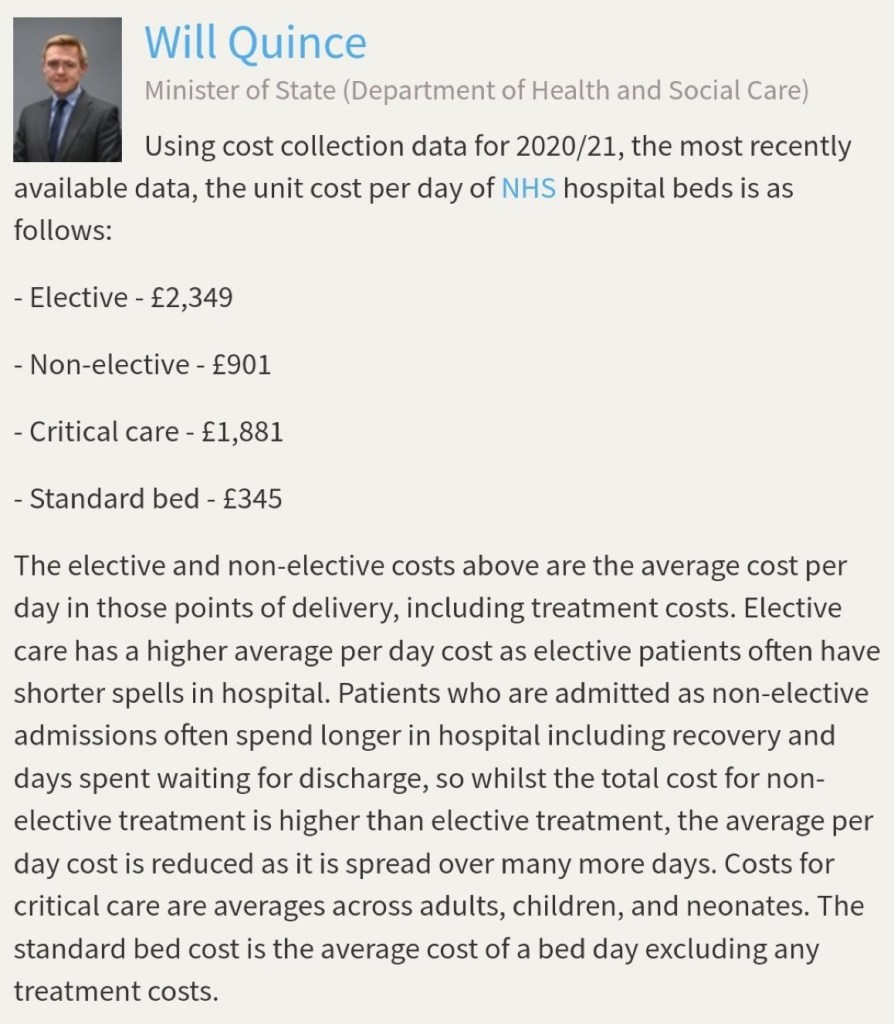

Yet there is no mention of any of this in the JCVI document published on 2 August. Surely the evidence presented above should be a key reason, even on its own, for doing everything possible to contain the spread of Covid, including widening access to vaccines, better public information, promoting take up of vaccines and clean air in hospitals and other settings?It is beyond doubt that measures would pay for themselves and would not constitute a cost to the economy as the benefits would be reaped in the short term as well as in the medium to long term. The costs to the NHS of treating Covid-19 infections must be staggeringly high – the figures below from 2021/22 (these will now be higher) were set out in response to a Parliamentary Question in 2023.

Conclusion

I hope that the budget and spending review take account of the points I raise. Provision needs to be made for extending access to vaccine boosters accompanied by a range of other measures, including clean air in public buildings, particularly schools and hospitals/NHS settings, clear public health messaging and better data in order that people are aware of the risks at different points in time and areas. The government also needs to be investing in research to develop better vaccines and treatments and reverse some of the damaging cuts made to the domestic science base in the recent past.

Link for submitting a response to the Treasury by 10 September 2024

Gillian Smith

28 August 2024

Leave a comment