On 25 April the Office for National Statistics published data on self reported long covid from the Winter Covid-19 infections survey. This paints an alarming picture of continuing high rates of long covid, and suggests a growth in the number of sufferers since data was last published in March 2023.

How many people have Long Covid?

Estimates based on the survey suggest that 3.3% of the population of England and Scotland (Wales and Northern Ireland not covered by Winter survey) reported having long covid – this is an estimated one in every 30 people – in other words 2 million people. When one factors in broad estimates for Wales and NI the figure is likely to be in the region of 2.3 million. This compares to an estimated 1 in 34 people reported in the ONS infection survey last March.

The numbers therefore appear to be rising which is consistent with what is happening in the USA. This contradicts the views being expressed by some people that everyone who was going to get long covid would have had it by now and we should expect to see numbers falling. It is true that vaccination has some impact in reducing the likelihood of Long Covid, though estimates vary widely. We also know that the more infections you have, the greater the chance of developing Long Covid – (see my blog on the Tragedy of Long Covid for a discussion of this).

Moreover, the data paints a sad picture of how much people are suffering.

“Long COVID symptoms adversely affected the day-to-day activities of 1.5 million people (74.7% of those with self-reported long COVID), with 381,000 (19.2% of those with self-reported long COVID) reporting that their ability to undertake their day-to-day activities had been “limited a lot”.

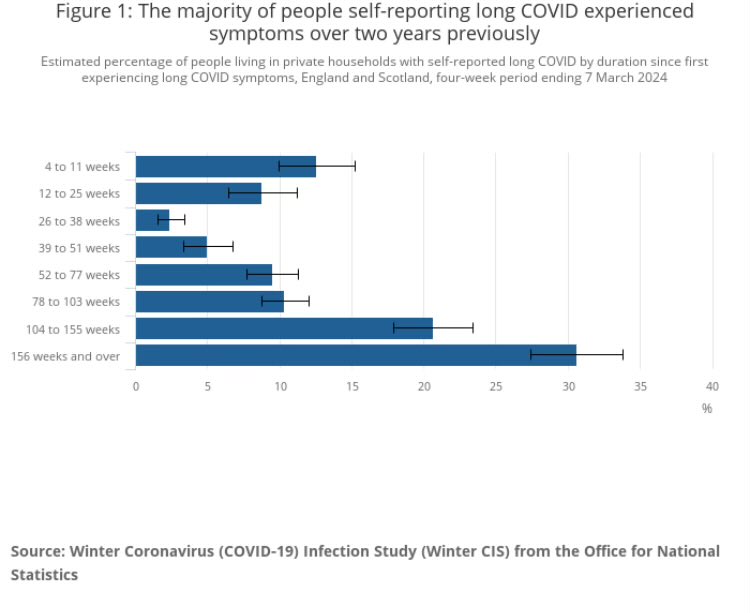

Even more alarming is the length of time that some people have been suffering. We can see from the graph below that as many as 51% of people with LC have been suffering for over 2 years and 71% have been suffering for at least a year.

A Disease of Middle Age?

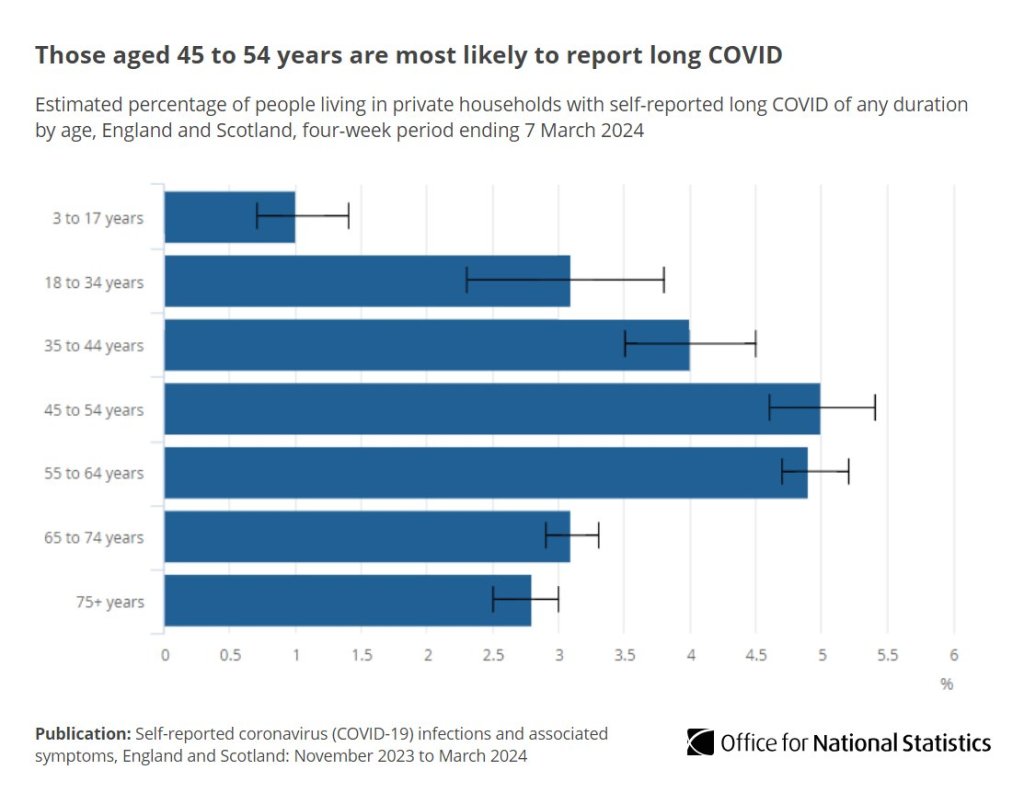

The proportions suffering from Long Covid vary depending on age. We can see from the graph below that nearly 5% of the core group of 45 – 64 year olds reported suffering from Long Covid – this is about 1 out of every 20 people in this age group.

This is alarming and it is very difficult indeed not to conclude that this explains a chunk of the growth in the number of economically inactive people in these age groups as discussed in my blog on the long term labour market impacts of Covid and the associated economic damage.

Of course the media will no doubt continue to ignore this elephant in the room when it comes to discussing withdrawal of older working age people from the labour market, but this will get even more difficult to ignore as time goes on.

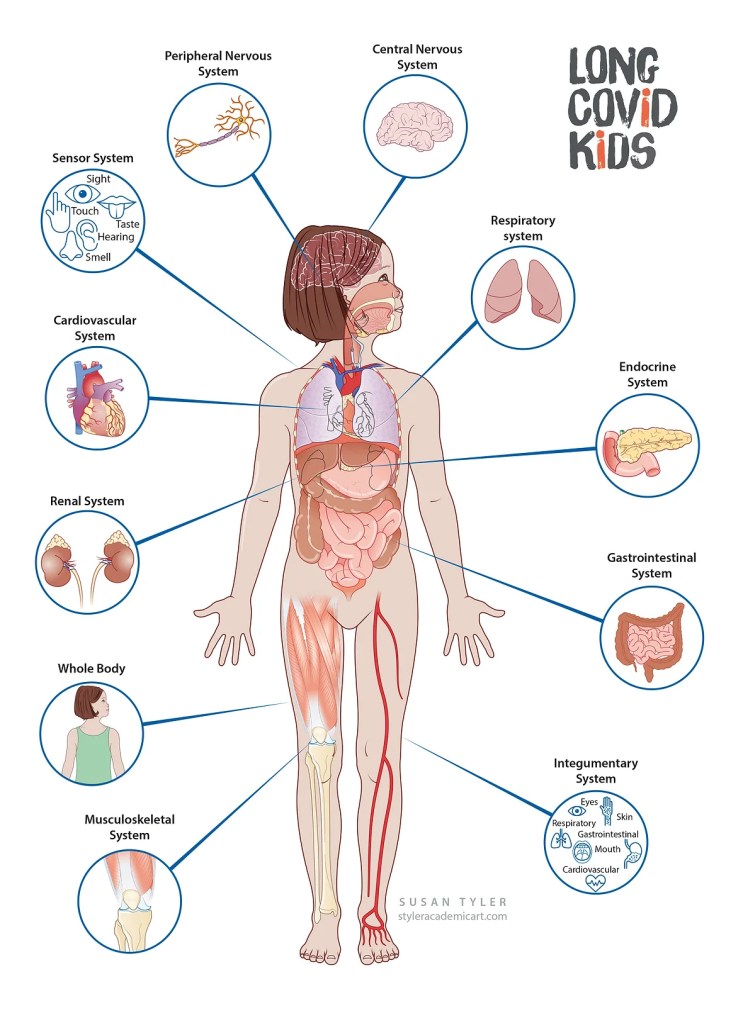

In sum, the survey shows a high proportion of people are suffering from long covid that impacts heavily on their lives. We know that this will be an underestimate because few people will attribute other illnesses to Covid, even though there is now strong evidence on the impact of covid infections on over 200 organs in the body including the heart, lungs and brain – see my blog on the tragedy of long covid.

It is also interesting to consider older people. We can see from the graph above that older people were less likely to report long covid symptoms. Part of the explanation for this is that older people are slightly more likely to be taking steps to avoid catching Covid in the first place, and they are also far more likely to be fully vaccinated. But another part of the explanation is probably that they are less likely to link their symptoms to Covid. If informal evidence is anything to go by we know that older people over 65 are more likely to blame old age for their ailments rather than Long Covid. It does not mean this group are fit and healthy, quite the opposite, but they are less likely to blame Covid.

Data on Rates of Infection

This publication also enables ONS to examine the rate of infection amongst population sub groups more than was possible in the fortnightly updates from UKHSA that appeared over the winter up to mid March.

One finding that stands out is the following observation:

‘For participants of working age (those aged 18 to 64 years), those working in teaching and education were more likely to test positive compared with those who were unemployed or economically inactive’.

It is difficult to imagine what stronger indicative data is needed on the impacts of the lack of infection controls in schools, combined with policies that encourage, or even mandate that children should attend school when ill.

Politicians are clearly concerned about the problems around the way in which the pandemic has impacted adversely on the educational progress of children. However, in my assessment focusing exclusively on the adverse impacts of lockdown is ignoring another large elephant in the room – namely the propensity of Covid infections to spread through schools resulting in illness and lower levels of resistance to other infections through the damage Covid inflicts on the immune system.

The impacts of making teachers sick is rarely considered, but it is fairly clear from this data that they are being made ill, will probably have to take time off, resulting in the greater use of supply teachers, which in turn is surely not in the interests of pupils educational progression.

The impact of vaccination on infection rates

The data published by ONS suggests that:

‘Those who have had a vaccination since September 2023 were less likely to test positive in the early waves of the study period (1 and 2 ie November); in later waves of the study period (3 and 4 ie December, January) there was no statistical difference.’

I think there are two key points to make here.

Firstly, the Autumn booster was restricted to a relatively small number of groups – (the over 65 year olds, those living in care homes, some clinically vulnerable people over 16, unpaid carers, household contacts of the immunosuppressed and health and social care staff) so it is not possible to explore the links between vaccination and infections for younger and middle aged groups as most of these people will not have been vaccinated in Autumn 2023.

Secondly, we know that over 2 million older and clinically vulnerable people received an old BA.4/5 vaccine in September 2023 (and sometimes later into the Autumn) as the new XBB1.5 adapted vaccine only started to be administered on 2 October. The old vaccine was subsequently found to be ineffective in preventing hospitalisations at a time when the JN.1 variant was taking off in late Autumn and this may well be a reason why vaccinated people were equally likely to get infected later in the Autumn/winter 2023/24 as this was a time when the JN.1 variant was surging.

It would therefore be dangerous to conclude, on the basis of this data, that vaccination has no impact on rates of infection. Indeed, in my assessment this data on long covid provides a very sound basis for arguing the free vaccines should be extended across the entire population due to the risk, particularly amongst middle aged people, of going on to develop long covid.

Children

Finally, it is important to look at children. It is clear from the data presented above that children are less likely to have self reported long covid symptoms. Nevertheless, about 1% of children do have Long Covid, and this represents a sizeable number of about 100,000. When one considers what the impact of having Long Covid at this age is for longer term education and career progression this should not be dismissed as insignificant. I will return to this subject in a subsequent blog.

Concluding comments

The tragedy of the sorry picture painted above is we know that the problems could be tackled with the correct policies. For example, in schools, proper air filtration would go a huge way to addressing the spread of infection, and in the shorter term the installation of strategically placed HEPA filters would bring significant benefits.

However, the mainstream media, politicians and parts of the medical profession continue to ignore the issue of Long Covid, no doubt because they think it is difficult to define and address. Indeed who would have thought five years ago that an ONS report saying that over 3% of the population were suffering from a new long term debilitating condition for which there is no cure and the numbers are growing, would only receive a few paragraphs, at most, in the main broadsheet newspapers. This should be headline news surely.

We need to make progress and to do this we need accurate up to date data. However, we now have no data and are heading rapidly back into the dark. The ONS winter infection survey has ended and there is no other data source and we are left yet again to rely on the USA and several other countries that do publish monthly data on self reported Long Covid. This situation needs to change.

Leave a comment