Earlier this year the World Economic Forum at Davos held a discussion about ‘Disease x’ and how to prepare for it. This blog discusses the issues focusing on the UK context in terms of preparedness for another pandemic.

I am fully aware that we are still in the current pandemic as confirmed by the World Health Organisation including on 6 February, and the virus is far from stable and could develop in a number of dangerous ways as discussed briefly below.

It is nevertheless useful to talk about preparedness for something different and, potentially, far more deadly.

Current Pandemic

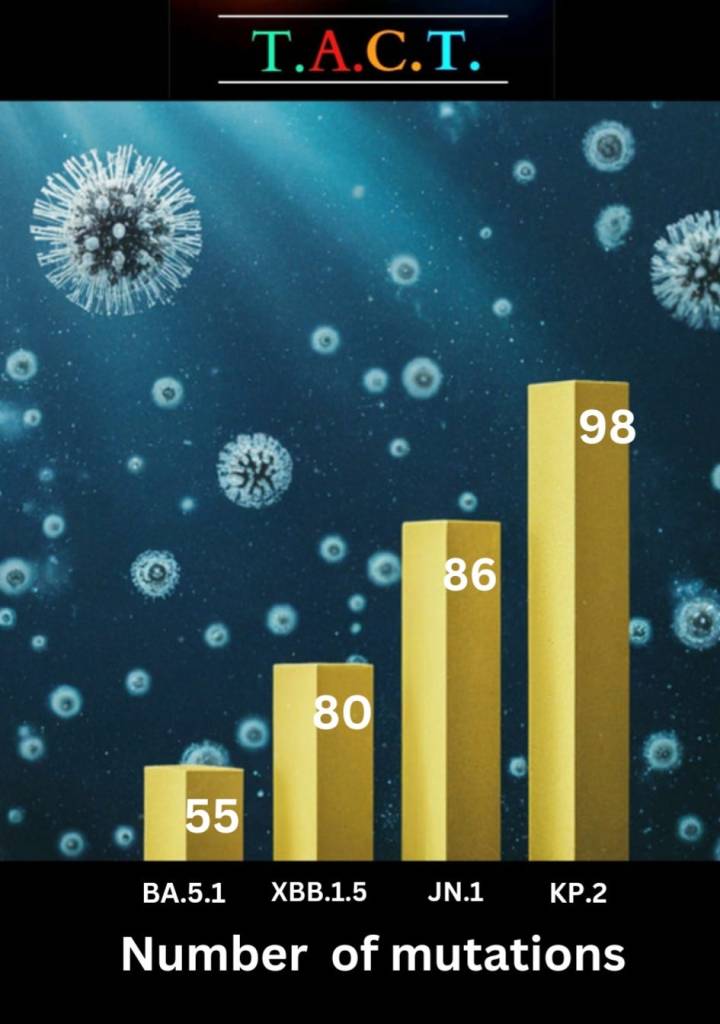

Many scientists are warning of the ways in which each new variant of Covid-19 is acquiring new capabilities as it adapts as is evident from the chart below from T.A.C.T. (Together Against Covid Transmission) , a well respected group of US scientists. We can see that the KP.2 variant which is currently showing an alarming jump in the number of cases in some countries that continue to undertake wastewater analysis has 98 mutations (compared with 86 for the JN.1 variant which swept through the UK this winter).

In a recent blog they summarise:

‘COVID-19 continues to explore new avenues to infiltrate human cells, accumulating mutations as it progresses in its evolutionary journey. The pace and trajectory of this evolution are highly alarming.’

T.A.C.T. March 2024

There are also increasing concerns about the consequences of increasing numbers of people – though this still only represents a tiny proportion of all infections – hosting several different variants at the same time.

As more people are infected with more than one variant it is intensifying the virus’s adaptive capabilities against our immune system. The high baseline of transmission ensures swift reinfection for millions, contributing to the virus’s persistence and its ability to generate more formidable variants within individuals

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-43391-z?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Future Pandemic

One needs a stiff drink before reading some of what is being written about future possibilities, but you will be pleased to know that I have tried to keep this blog focused at the general level on preparedness other than delve into this detail!

The discussion at this years Davos focused on preparedness for future emergencies that impact on healthcare systems. The particular focus was on ‘Disease x’ which could be up to 20 times more deadly than Covid-19.

The key conclusions are captured in this press report from ‘the Guardian Nigeria‘ news are that WHO is calling for a World Pandemic Treaty and the hope is that agreement on this can be reached by May 2024. A spoken English version of the discussion is enclosed in this link.

Related to this, in 2021 many countries started working towards something called the ‘100 day challenge’ i.e. how to contain a virus spreading whilst a scientific response can be approved, manufactured and delivered within 100 days. However, the momentum has been lost in recent years and needs to be re-stressed.

Sources of the next pandemic

Disease x is described as a hypothetical “placeholder” virus that has not yet been formed. China may be doing more work on tracking and preparing for this than any other country.

Easier to envisage potential sources of the next pandemic range from bird flu transferring to animals, (including very recent cases reported in the USA , involving bird > cow >? human and cats transmission), and being able to spread directly between humans – the CDC (Centre for Disease Control) in the US has called for states to be ready with rapid testing; a spreadable ebola type virus on a global scale, a flu pandemic similar to the 1918 pandemic, something involving insects, and even the melting of the polar icecaps and releasing ancient viruses.

Overall, it is increasingly accepted that climate change makes it more likely that we will have another global pandemic in the foreseeable future. In other words, in the life time of most of the people reading this blog. In the words of Sir John Bell in his recent evidence to the Science and Technology committee:

‘I would bet the house on it. It is definitely going to happen, so everybody should just get used to that. The real question is what the likelihood is of that happening in the short term. It will definitely happen in the medium or long term, for sure. As you know, there are many things pushing humans together with a wide range of other species. We are doing a lot of things that are very high risk. Climate change is not going to help with that, because insects are moving all over.’

Some of the better estimates suggest that there is a 20% or 30% chance of having another pandemic in the next 15 to 20 years. That is a big number. Whether it is a really profound pandemic or one that is not so bad, we will have to wait and see, but it seems inconceivable to me that we will not have another big event’.

Sir John Bell evidence 4 March 2024

There is also a great deal of almost science fiction type stuff about viruses being created in laboratories and being released deliberately as part of a kind of germ warfare or accidental release from labs. For example there has been significant recent interest in developments in Wuhan, China where it is claimed that scientists have created a virus which when tested on humanised mice suggests that it may be able to kill 100% of humans that it infects.

Key Lessons

Wherever the next pandemic comes from the WHO and others are without doubt right that the world needs to be nimble footed in surveillance and in its response and this needs to be global and transcend the interests and policies of individual national governments.

Another key takeaway is the need for governments to spend far more on preparing their health systems for the next pandemic and focusing more on prevention. Michel Demaré, chair of the board of AstraZeneca, warned the panel that OECD countries spend on average only 3% of their health systems’ budgets on prevention. He went on to make the point that if you spend so little on prevention, you end up spending the majority of your budget on hospitalization and treatments.Demaré also emphasized the need for countries to share data transparently, floating the idea of creating international libraries of diseases and vaccines.

Benchmarking the UK

Whilst the WHO is right about the need for a global response that is better than the response to Covid-19, it is nevertheless the case that powerful national governments are likely to resist any international body having too much power over and above an advisory role.

The experiences of local populations will depend largely on what is going on their own country and the preparedness of their national governments, their ‘political’ willingness to learn from the past and from developments elsewhere, and co-operate in formulating a global response.

So where might the UK stand on this? Taking the key points laid out by WHO I assess the level of preparedness.

Early Warning Systems

The panel placed a great deal of emphasis on early warning systems. Some of this can be organised at global level, particularly if it is known where the threat lies – for example, monitoring the melting polar icecaps for new (old) diseases. However, a global system would also depend on individual countries or coalitions of countries all undertaking work and sharing timely data. It is notable that the country which appears to be taking surveillance most seriously is China which does not have a good track record in sharing data.

Whilst funding pressures across the globe are a threat to developing or even maintaining early warning systems, most other Western countries have maintained wastewater analysis and are better able to signal the arrival of new diseases of concern. We don’t know whether this would be helpful in signalling the arrival of something new that is capable of turning into a pandemic, but it would certainly be helpful in monitoring whether the current pandemic is taking off in a dangerous direction. I would be strongly in favour of this being reinstated across the UK.

The WHO or whoever takes the lead would need to have real clout and leadership to ensure the kind of data sharing outlined by Sir John happens in a way that forms an effective early warning system.

Organisation of supply chains

WHO envisages a regional and global production and distribution system of medical and public health countermeasures such as tests, vaccines, medicines, diagnostics and personal protective equipment.

How far individual countries would be willing to co-operate with this is another matter. During the current pandemic richer nations have used their buying and distribution powers to get hold of supplies ahead of poorer nations. And there have been jealousies between the richer nations, including between the EU and the UK about who is ‘winning’. Take, for example, Boris Johnson’s boasting about the UK being the first country to roll out a vaccine programme.

In the case of a new global and more deadly threat this would need to change, but I am not sure how this would happen, in reality, in the UK. Certainly, it would be important to take account of existing studies of how public procurement in health care might be improved – including a 2021 report from the European Commission as well as the UK Covid Inquiry module on this subject.

Research and Development

Sequencing platforms are key to forming a basis for subsequent vaccine development and treatments.

In his evidence to the Science and Technology Committee on 4 March 2024 Sir John Bell explained that:

There is potentially a system out there that you could build quite quickly. Interestingly, there are really only two sequencing platforms at the moment that could be used for pathogen sequencing at scale. One is Illumina, which is a very good platform run by a big American company. The other one is the Oxford Nanopore platform, which is run by a UK company, which is probably ideal. ..

The UK could reach out and, possibly through the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, get to the wider UK Commonwealth community and get people to start working together a bit more effectively on generating sequences, but crucially, putting those sequences in some kind of single, cloud-based database that is validated and available for use.

The biggest single obstacle is that people don’t want to share data. We are not sharing data about people. We are sharing data about bugs, and it doesn’t seem to me to make a lot of sense not to share data about bugs, particularly when they could come back and bite us all.’

Sir John Bell

The key objective will obviously be to generate new medical products and vaccines once the genetic sequence of the pathogen is identified.

The key challenge is to move at the speed required. The coronavirus pandemic led to a sense of urgency – Professor Sheena Cruikshank discusses this and how, although the vaccine was developed at breakneck speed, this does not mean corners were cut. Sheena highlights that the reasons why vaccines usually take so long to develop and approve reflects the time taken to get funding, bring together collaborating researchers, the lengthy and bureaucratic nature of ethics and other committee procedures, getting trial volunteers recruited etc.

The unprecedented emergency posed by the Covid pandemic in 2020 allowed these timescales to be drastically reduced because of flexibility of funding bodies, significant co-operation and pulling together of researchers across disciplinary boundaries in the face of an international emergency and the keenness of the public to come forward and volunteer for trials. Ethics and other committtee’s also demonstrated significant willingness to do their job to the same standards as normal by prioritising the Covid vaccine development over all other matters in their in-boxes

However, there are worrying indications that the UK is in a worse position than in 2020. Sir Clive Dix who was Deputy Chair of the UK Vaccine Taskforce the told a group of MP’s on the Science and Technology committee late last year that :

” there had been “a complete demise” of work to ensure the UK was better equipped with vaccines for the next pandemic, noting that all the activities were “literally gone”.

And:

“Beyond failing to invest in a range of vaccine technologies, the UK also drove vaccine manufacturers away by treating them so poorly, Dix added, leaving the country in an even worse position than before Covid.”

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2024/jan/24/uk-less-prepared-for-pandemic-than-pre-covid-former-vaccine-chief-warnsAnd:

Professor Andrew Pollard, director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, said the danger was in preparing for a future pandemic exactly like Covid. While Covid vaccines took nearly a year to develop, they built on years of crucial research on coronaviruses. Work on dozens of other potential pandemic pathogens lagged far behind, he said.

The Guardian see above

Following on from this the House of Commons Science and Technology and Health Committees held two further sessions on 28 February and 4 March 2024. In his evidence Sir John Bell said he was greatly concerned that everything was being run down or turned off. He explained that the world had got away relatively lightly during this pandemic because the vaccines were relatively easy to design. But this was not inevitable. He made a strong case for an ‘always on’ approach.

We have a corporate responsibility for making sure that the bits that you need to respond properly are in place, are running, are operating and are warm, so that they are always on and you can pivot to these things. What we learned most of all is that if you start from the beginning and you have to turn stuff on, it takes too long. If you were having a pandemic that was killing lots of small children, for example, or was killing 40% of the people it infected, you would not want to be standing there, but we would be, I am afraid, if we had to start again.

Sir John Bell

Unfortunately, in her evidence, Jenny Harries, Head of the UK HSA (Health and Security Agency) was not convincing about what needed to be done and whether (and when) the UK was going to do it. For example:

‘we may have a pandemic tomorrow; we may not have one for another 100 years. I think the MP here was flagging some of the ongoing costs. These are opportunity costs for other areas of expenditure.’

Jenny Harries evidence 28 February 2024

The chair then picked up the point that in her September 2023 evidence Harries had reassured the committee that the two centres referred to by both Dix and Pollard above would provide what was required, yet these were now due to be closed down. In her evidence Harries wriggled around but eventually did acknowledge that they would close in June if the end of March deadline were to be extended. She also mentioned that the labs in question might not be as useful if a completely different pathogen or pathogens where to emerge, but neither did she outline any ideas on what actually might be needed.

This confusion between the current pandemic and preparedness for a future, different pandemic, ran throughout the evidence and the chair may not have done enough to ensure focus.

Rebecca Long Bailey’s questioning is interesting. For example,

Q392 Rebecca Long Bailey: In your expert opinion, does your organisation as it stands now have sufficient resources to be prepared for a deadly pandemic if it happened tomorrow?

Professor Harries: For the parts I can define I can say that, but no public health protection agency in the UK that I know of, historically or now, has ever been funded fully to mount a full response as we have seen to a pandemic. It would always be something of that proportion, and one would then turn to Government because it would be a national emergency. …I am trying to be really clear in maintaining the science and scientific knowledge and grow that. ..

Q393

Rebecca Long Bailey: Your agency is responsible for pandemic preparedness in the UK. While I appreciate you work with lots of different moving parts and organisations, you will have an overview of the amount of funding and resources that would be required for a pandemic if it happened tomorrow. The question I ask again is: do you think that the UK is fully resourced and funded sufficiently to be prepared for a pandemic if it happened tomorrow?

Professor Harries: I am not the agency. The Department of Health has the responsibility for pandemic preparedness and we work with them. I am not trying to ignore your question, but the answer is simply that we need to be clear what it is the country wants to retain. Is it everything that we have—850,000 tests a day sitting idle—or do we want to have a smaller capacity going forward?…

Q394 Rebecca Long Bailey: For the Committee and people watching, the contracts with the two labs that we discussed issues with earlier are coming to an end in June. The UKHSA would have nothing to do with the funding of those labs and would not be making representations to Government. Am I right in saying that?

Professor Harries: That is not quite what I said. The contracts for those labs have been funded as part of the past covid pandemic response. We are moving back to managing infectious disease, including covid, as usual. If we do not have those contracts, we will be managing covid in the same way as we would other respiratory viruses. We have surveillance systems; we have laboratory testing; routinely, we work with the NHS.

We are doing all of that, but those contracts were part of a step-up system. We can do our bit, but the country needs to decide. It is not for me; it is a ministerial decision. We have seen already with the public inquiry that the impacts of the pandemic are so significant that that discussion sits with UKHSA involvement. We can make recommendations on testing and the scientific technical side of it, but the discussions on investment are beyond the organisation alone.

Q395 Rebecca Long Bailey: Have you made any recommendations or requests to Government to extend this funding for such facilities?

Professor Harries: We are working with the Department of Health in a number of these areas—testing and vaccines work as well—to indicate where we think there will be benefits, and it is for Ministers to consider those. They are doing that on an ongoing basis.

Q396 Rebecca Long Bailey: Are there any specific figures you would be able to disclose today in terms of the requests you have made to Government?

Professor Harries: In terms of funding?

Rebecca Long Bailey: Yes.

Professor Harries: No, because this is a decision about risk appetite and risk management to start with.

See reference above

I think all of the evidence presented above points to the need for the role of the Head of the UKHSA to be clarified as I find all of this worrying. At present Jenny Harries does not seem to be able to articulate what needs to happen to prepare for a future pandemic, the different options under different scenarios, taking account of the risks involved in each, and the cost implications. Yet it is arguable that this is her job as laid out in the UKHSA Forward Plan. What is not her job is to then consider the opportunity costs of doing or not doing what she outlines as necessary to plan for a future pandemic – that would indeed be for Ministers (not her) to decide as they are directly accountable to the public through democratic elections.

But where we seem to be at present is that Ministers are not being given options. Clearly, the looming general election is likely to disrupt the business of government, but this is an urgent matter to return to after the election.

It has also recently emerged that the UK government is withdrawing financial support to the world leading ‘UK recovery programme’ which has led the way in developing and testing new drugs and the development of vaccines. This is only managing to continue because of the support of a small number of US philanthropists.

This really goes to the heart of the debate about the independence of scientists which I return to below. In my assessment the UKHSA is clearly not independent – the relationship with ministers is too messy. Roles need to be urgently clarified and greater transparency needs to be injected into the processes.

Public hearings on Module 4 of the Covid Inquiry on vaccines and therapeutics are due to start in early 2025. We don’t know what the reporting timetable will be but it will be relevant to discussions about the next pandemic.

Primary Healthcare Organisation and Capacity

As demonstrated by the experiences during the continuing Covid-19 pandemic, health care systems need to be able to ramp up to deal with unknown viruses. Challenges here include how to plan for viruses that could spread in a variety of different ways as this has profound implications for how to organise health care, treatments and inform what protective measures need to be put in place.

The UK does not look good on this measure as illustrated in this short clip from channel 4 news and many other sources. Waiting lists for existing treatments are at near record levels, some hospitals and other facilities are crumbling due to lack of attention of maintenance and updating, staff are leaving in droves, including for better paid jobs in other countries with better conditions, and staff are generally exhausted and demotivated, and social care provision is hugely stretched.

On top of this the population is becoming sicker, driven by lack of access to healthcare, population ageing, high levels of absolute poverty, increasing inequalities, increased insecurity including in the housing market, as well as Long Covid and conditions generated by covid eg increase in heart attacks and other very serious conditions. All this means it is likely that demand for healthcare will grow in future.

Also, preventative work is very important in this context as it is likely to be the case that population resilience to new diseases will be lower if they are already sick with sometimes invisible chronic diseases. But resources devoted to public health preventative measures on problems such as obesity, mental health, and diabetes has fallen in real terms in the last few years.

The final part of a recent blog from Bob Hawkins summarises how badly the UK is performing on key measures.

We can see from the graph below how badly off the UK is for both hospital beds and doctors per person.

The picture isn’t any better when we look at the availability of CT and MRI scanners. And OECD data suggests the UK has only half the number of ICU beds than the OECD average of 14 ICU beds per 100,000 population.

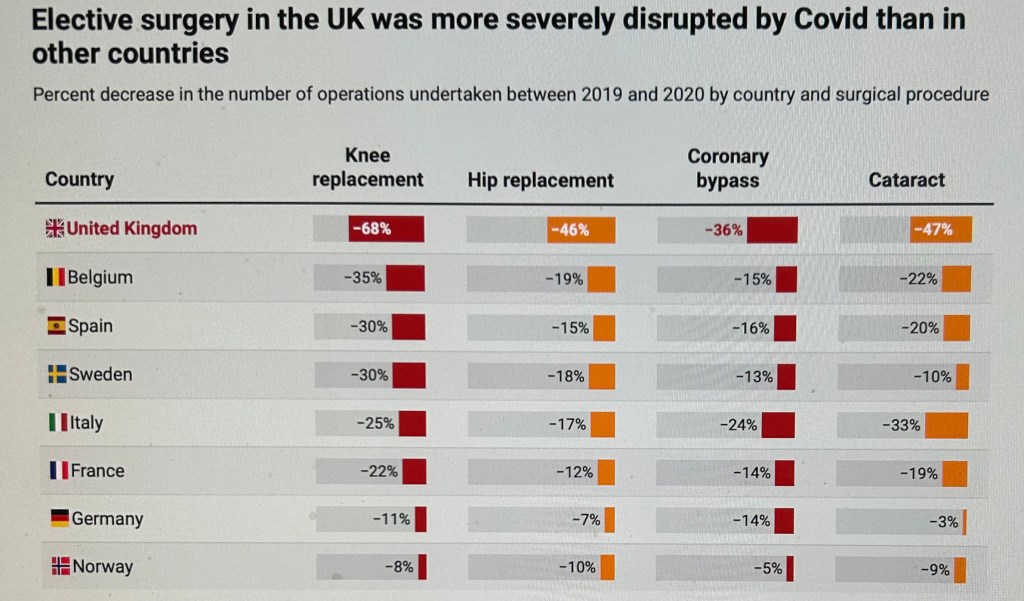

The consequences of these comparisons go some way to explain the high number of deaths from Covid in the UK – along with a general failure of government policy. But it also explains the difficulties the British health service had in bouncing back after the Covid emergency period and is one of the key reasons for the growing waiting lists.

The challenges are therefore enormous in terms of being able to respond to a major emerging threat quickly and recover from it quickly. The NHS clearly needs an injection of funds and policies that will stabilise the workforce from hemmoraging further, but it is not clear whether this is going to happen in the short – medium term.

Module 3 of the Covid inquiry is due to get underway in the Autumn of 2024 to consider Healthcare systems. It is hoped that this will be able to take a strategic view about how to prepare for unknown pandemics as well as looking backwards at, for example, the over optimism of the former health secretary Matt Hancock.

In the light of these and other data and the time it will take for the NHS to recover, it is clear to me that the UK needs to be more, and certainly not less decisive and sure footed in its response to emerging threats compared to other western countries in order to stop any new disease in its track and prevent healthcare systems from collapsing.

Data on prevalence/spread and impacts

Tracking prevalence of any emerging diseases is vital to enable policy makers to assess the risks and inform how to manage them. First and foremost we need to have access to testing labs and a test in order to determine whether someone has the new disease. This is a challenge and the discussion above under R and D is central to this.

The discussion of early warning systems above also highlights how the UK and many other countries have dismantled more or less all reliable sources of data. The stopping of the nationally representative ONS infection survey at the same time as halting analysis of wastewater means the UK is to some extent flying blind in terms of its ability to track what is happening with recognisable illnesses.

In some ways we are in a better position in terms of know how in developing and implementing a population survey such as the original ONS Infection survey adapted to monitor new illnesses quickly on the grounds that we have done it before and we have a sample (although this will need to be refreshed). However, in other respects we are worse off because the laboratories have been or will be closed down. Some of these had been open since well before Covid and putting this infrastructure in place, and recruiting staff with the right skills would take time, which we are unlikely to have.

Contact tracing – reducing the spread

Some countries such as South Korea had very effective systems in place to trace the contacts of those infected and effectiveness control the spread of the virus and reduce the number of serious illnesses and deaths without the need for lengthy lockdowns and without health systems collapsing.

The UK abandoned initial attempts at contract tracing before the pandemic had taken hold and the subsequent dithering and surge in infections meant it was impossible to subsequently get a grip on attempting to control the fast spreading virus.

The UK then adopted NHS ‘ Test and Trace’ from Autumn 2020 under the leadership of Dido Harding. The total cost of the entire process was nearly £30 billion and is widely judged to have been a failure in preventing the significant spread of infections. In spring 2021 a highly critical report from the National Audit Office, reported in the BMJ concluded that serious problems remained with the overall speed, reach, and levels of public compliance of the NHS Test and Trace service, and called for improvements to be made ahead of so called ‘freedom day’ in July 2021. These improvements never surfaced, not least because of the language used in presenting ‘freedom day’ which in the minds of many people was seen as meaning ‘it’s all over’.

There is a need for a serious assessment of what went wrong that focuses on what we could do differently in future, including drawing on the experiences of other countries. Some have argued that the job could be done more effectively at the local level through public health officials in local authorities. However, a key snag here is that the number of local public health officials has been cut back drastically in recent years and these cuts would need to be reversed if local level officials are to be expected to play a major role in a future pandemic.

However, regardless of how it is organised, I think it is clear that a workable strategy based on identifying and isolating those infected of the type adopted in South Korean would pay dividends. This is discussed in a recent piece by Anthony Costello in which he concludes that it is possible that as many as 180,000 UK deaths out of 237,000 deaths in total might have been saved had we adopted the South Korean model. It is also notable that we would have been saved all of the damage done by the long lockdowns endured by the UK.

Additional important factors

There are a range of additional factors that could determine how successfully the UK and other countries respond to a new global threat. We discuss three of the most important here – the organisation of Scientific Advice, Leadership and communication, and Clinically Vulnerable Families.

Organisation of Scientific Advice

Whatever type of pandemic we have to confront in the future, scientific advice involving effective collaboration between countries will need to play a pivotal role.

There have been numerous problems with the organisation of science advice during the current pandemic, particularly around secrecy, closeness of scientists to Ministers and a general blurring of the dividing line between science and politics. We have, for example, seen a stark example of this in the evidence given to the Science and Technology Select committee last month and discussed above.

During the height of the current pandemic the SAGE committee was meant to provide a key source of independent scientific advice but in contrast to how SAGE normally operates in an emergency, it included several political advisors from inside number 10, including Dominic Cummings and Ben Wallace. It may not have been truly independent. The committee was also heavily criticised because it did not operate in a transparent way, particularly during the early stages of the pandemic when even the membership was kept secret along with the research papers and minutes.

A key critique of SAGE made by several witnesses to the Covid Inquiry is that too much emphasis was placed on presenting a consensus line to ministers when no such line existing. In reality, the different members of SAGE tended to differ in their views and some feel that there should have been formal minutes which reflected the range of opinion and debate in more accurate terms.

A truly independent body will be needed in future to provide government scientific advisors, institutions and, very importantly, the general public with independent evidence and advice.

In my assessment Independent Sage provides a good potential model. Early on in the current pandemic and in response to how SAGE was operating, the former government chief scientist, Sir David King, set up a new completely independent committee that met in public via zoom and in contrast to SAGE was completely transparent. Indie Sage has, in my opinion been a success and a ramped up version could be even more successful if resourced adequately. As is evident from the Indie Sage website the range of papers, briefings and media interviews have provided an accessible resource for anyone interested in the pandemic.

Also given that many of the questions around the management of a pandemic are social and behavioural, social scientists need to play a far bigger role in future. In particular, it is important that social scientists don’t focus their efforts solely on setting up new research programmes to address questions being thrown up during any emergency, but focus on what they already know to contribute to the discussions in a proactive way. They need to start planning for this.

Leadership and Communication

Leading a country through a pandemic is clearly going to be challenging. However, the UK example of a major Western country attempting to handle the current pandemic is in many respects, at least in my assessment, a good example of how not to do it. Also see my blog on the weeks leading up to the Spring 2020 lockdown.

The truth about the sheer scale of mistakes made is carefully documented in the following excellent book by two journalists from the Sunday Times focusing, in the main, on the first year or so of the pandemic.

Clearly we will need to do better next time. In my assessment we do need to collaborate globally to a far greater extent, through WHO or something similar.

We also need to learn quickly from the lessons emerging from the Covid Inquiry so far, but also look beyond this to the global picture. Whilst the inquiry will without doubt be useful, I agree with Pagel and Magee writing in the New Statesman in December 2023 who state that it is disappointing that the Covid inquiry has not so far at least explored whether we should have been co-operating more with other countries and what form this co-operation might take. The inquiry has focused largely on what happened and how it happened, rather than considering what could have happened.

Most of the examples which are widely regarded as models for the future are located outside Europe – South Korea, Singapore, New Zealand. It is surely important for the future, particularly if we are to be faced with a more serious emergency, that we look at how policies in these countries worked and how they could be adapted to the UK/European context and then work out how to implement these lessons.

This is not to imply that there were not good examples from closer to home in Europe, particularly before vaccines became widely available. For example, Germany did a great deal to protect care homes and mask wearing and air filtration was far more widespread than in the UK. We need to learn these lessons and ensure they are widely understood.

As summed up by Pagel and Mageee 2023:

it is clear that countries which acted quickly and decisively to reduce the spread of the virus until a vaccine was available did better in both health and the economy. Why did counsel for the (Covid) inquiry not ask ministers and the new chief science adviser Angela McLean what structures the UK has created to learn from other countries as we continually revise our crisis response plans?

Pagel and Magee 2023

Clearly, the UK needs to undertake some serious analysis work on the options for responding to a pandemic on things like lockdowns, schools, care homes, the economy, communications, returning to some kind of normality afterwards in a consistent and effective way which recognises any continuing challenges that need to be managed.

The nature and organisation of policies will of course depend on the particular challenges posed by any future pandemic. It is perfectly possible for example, that any future virus could impact on babies and children more than other groups and this would have obvious implications for the policy response.

It is nevertheless the case that important lessons can be learnt from the current pandemic and the Covid inquiry which is due to produce its first report this summer has a key role here.

Clean Air

Also, numerous scientists, pressure groups and individuals have been advocating for clean filtered air, in public buildings – including schools and hospitals, as well as disseminating information about the benefits of clean air and simple ways of improving ventilation in all indoor settings.

We do not know of course whether any future pandemic would be an airborne disease, but there is certainly a very good chance that it will be. In the event of this happening, having clean air in buildings would pay huge dividends. Investing in short and long term solutions to achieve clean, filtered air in indoor settings would also pay dividends in helping to contain the current pandemic and give CV families their lives back by enabling them to attend venues that are currently out of reach.

Clinically Vulnerable Families

At the start of the current pandemic the government did at least pay lip service to the needs of clinically vulnerable people. This did not always result in effective policies, take for example the promise made by former health secretary Matt Hancock to place a protective ring round care homes and then proceeding to discharge Covid positive hospital patients into care homes.

Nevertheless, shielding arrangements were put into place to help protect the CV, though again, promised supermarket slots and food parcels did not always materialise. Shielding was also, on occasions, heavy handed and failed to recognise the practicalities of the daily lives of the CV and their families.

As the immediate emergency passed and the country moved out of lockdowns, this initial concern has wavered. Essentially the clinically vulnerable, many of who do not receive protections from vaccines, have been left to fend for themselves in what feels like an increasingly unsafe environment of highly infective strains of Covid, very few mitigations and a general lack of interest and, at times hostility, from others.

Protections in workplaces are often minimal, the process of negotiating reasonable adjustments is fraught with hurdles, accessing healthcare and education safely is often a nightmare and maintaining or obtaining home working or home schooling is increasingly difficult as a kind of ‘presentism’ seems to have taken hold across various sectors of the economy and society.

Household members of clinically vulnerable people like myself often have particular difficulties in negotiating safe arrangements because special arrangements for the clinically vulnerable rarely apply to the entire household, despite the fact that household members could pass the virus onto the clinically vulnerable person/people they live with.

Although we do not know which groups will be impacted on most by any future pandemic it is very possible that the clinically vulnerable will be heavily impacted, even if it is a pandemic that hits children and young people the hardest. Whatever happens we need to do better in any future pandemic, as well as the on-going one, and also think about what needs to happen beyond the emergency phase and ensure that it is inclusive.

Conclusions

This blog represents my first, and no doubt partial stab at the issues. The WHO is due to report in May following the discussion at DAVOS and the Covid Inquiry is also due to produce a report of module 1 before the summer 2024 recess (assuming a general election does not interfere with this timetable).

Nevertheless, it is clearly necessary to urgently put in place the resources, systems and experts needed to plan for a future pandemic or deal with a significant escalation in the current pandemic. This needs to be cross boundary, dynamic, cross disciplinary, independent and focused on responding to threats.

At the domestic level, the UK needs to learn from past mistakes. We clearly don’t know about the type of threat that any new pandemic would pose, but we should aim to keep the words of Sir John Bell at the forefront of our minds, namely, ‘the world may have got off lightly this time round’.

In my assessment key ingredients to a successful response are:

- Monitor emerging threats and agree a strategy with the international community on what needs to be done;

- Be ready – have the scientific capability and platforms needed to quickly find treatments and vaccines to any new disease and share information openly with other countries;

- Do not make the mistake that the next pandemic will be like Covid-19 – this was a fundamental and deadly mistake made during the current pandemic when all planning was based on the assumption that we would have a flu pandemic.

- Learn from what worked during the current pandemic – particularly the lessons from South Korea – particularly in containing the spread. Plan along these lines and for data collection needed to underpin test and trace either at the national or local level;

- Ensure clarity about the roles of independent scientists and science committees vis a vis politicians.

- Have a clearly worked out communication strategy underpinned by independent scientific advice;

- It is essential that we successfully tackle the current pandemic before we are hit with a new and different one. We need clean air, air filtration and to re-learn and communicate old lessons about the benefits of good ventilation. This would pay dividends in the short and long term and would also bring significant economic benefits;

- Sort out the NHS and care sector – stabilise and motivate the workforce through higher pay and other methods.

- Invest in high quality PPE and other equipment and stockpile it,

- Invest in public health and have a plan for reducing health inequalities and providing care;

- See lockdowns as a last resort, but if lockdowns are part of the solution, lockdown early and contain the spread of any virus. This should mean shorter lockdowns and less economic and social damage. However, this need for rapid action is not helped by having fool headed politicians around who have pledged never to lock down again. Our future leaders will require real vision and determination to push through measures that will avoid the UK repeating the same mistakes again.

In sum, all countries, and particularly the UK, are experiencing a tightness of public finances and making the case for raising spending on pandemic preparedness will also require real political vision and determination. This needs to be underpinned by independent, expert, transparent, publicly available advice in order that the public is fully aware of the risks their governments are taking.

Gillian Smith

April 2024

Leave a comment