Introduction

A couple of weeks ago the Guardian ran a piece: ‘A public health message for this flu season: please keep your snot to yourself’ in which the author highlighted the seeming reversal of behaviour compared with before the pandemic, suggesting that people don’t seem to care if they spread germs around and refuse to do simply things like sneeze into a handkerchief. Many people, including the clinically vulnerable and disabled or those caring for them will recognise this. There is a perception that people are generally less tolerant of us having special needs than in the past.

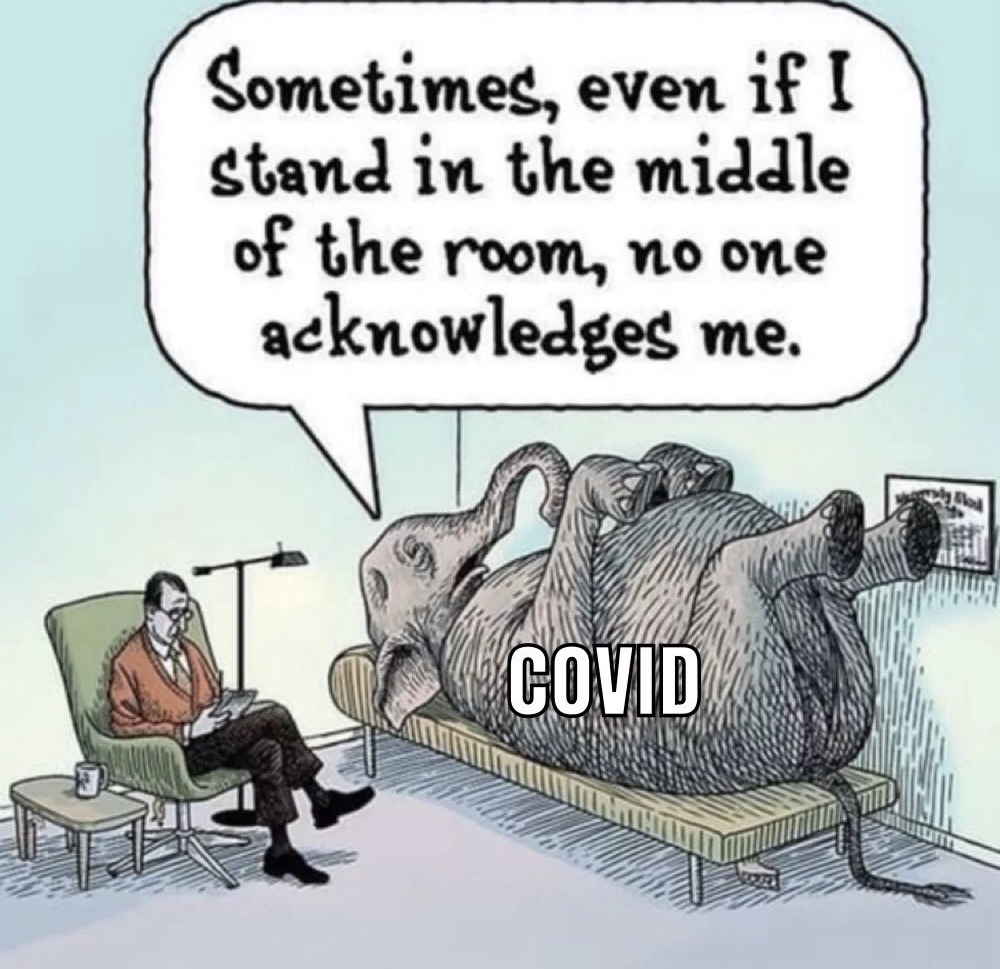

So, what is driving this and is it a barrier to ever successfully addressing Covid and other diseases?

This blog discusses the political messaging such as ‘freedom’, ‘let’s pretend it has gone’ along with Partygate, which I regard as one of the key underpinning factors behind what we are witnessing, before moving on to discuss possible economic, social, health and psychological explanations.

Unfortunately there is very little empirical evidence on the extent to which there has been a shift in public attitudes and behaviour, but it feels true to many of the people, including myself. This is not to imply that everyone has changed, but there is certainly an impression that a shift in attitudes and behaviours is taking place.

The Pandemic and its aftermath

The UK seemed to shift from an era ending in early 2020 where many, though not all, people were sympathetic to people when they were ill, and the majority were willing to help and accommodate physically disabled people, up to a point.

Then at the start of the pandemic in March 2020 things changed for the better and there were numerous reports of people reaching out to help others during a time of national / international crisis. This is certainly true of the area I live in. There may have been a slight waning in the winter of 2021, but it was still there.

Then as the pandemic waned, at least in the minds of many people once they were vaccinated. This was fuelled by parts of the media including the BBC. Things began to go downhill sharply in terms of behaviours towards those who wanted to and needed to stay safe and well. Hence the examples of aggression towards mask wearing and general foulness towards people who need/want to keep themselves and their families safe reported in the conclusions of my blog on Avoiding Covid, and also the public attitudes section of my blog on the Tragedy of Long Covid.

We can probably pinpoint the main trigger to the shift as the so called ‘freedom day’ of July 2021 when PM Boris Johnson announced to a fanfare that all restrictions were being lifted. Many people thought that was the end of it all despite the fact that infections were still very high and evidence from blood samples revealed that some people who wanted to protect themselves like my close family member and many others, had not responded to the vaccine.

Then later in 2021 the Partygate story about numerous illegal or semi illegal parties taking place in number 10 and elsewhere involving prominent figures in government began to break. This all gained traction following the Met being called in to investigate in January 2022 and the subsequent report by Sue Gray which highlighted the failures of leadership and concluded that whatever “the initial intent”, many of the gatherings breached Covid rules, and whatever the pressures of the time, this should not have happened.

If the British public needed any further persuading that we were not all in this together, Partygate provided it. People who had diligently followed the rules and made huge sacrifices in the process by for example, not going to funerals, keeping a distance, not visiting ill or dying relatives etc were rightly outraged along with much of the rest of the population. Personally speaking I spend a proportion of each day during June and July 2020 hovering about outside a large cancer hospital whilst my close family member received treatment delayed from early spring 2020. Every day people would come out of the hospital alone and dissolve into tears at the person waiting for them outside. I just wonder what all of these people, who probably received ‘bad news’ alone, thought when the Partygate stories started to break. And one thing that really fuelled the outrage, amongst royalist members of the population at least, was the replaying of images of the Queen sitting alone at the funeral of her husband in April 2021.

On top of this, and over the same period, the government effort to persuade people that it was really OK to keep getting infected as long as they continued to go out to work and kept spending really took off. Indeed, this was coupled with a lot of talk about the mad idea of the immunity debt. This is discussed further in my blog on the subject.

This theory that lockdowns were really a bad thing and continuing rates of illness could be explained by the fact that we needed to pay our debt for staying safe during the worst of the pandemic was attractive to the right wing media in Britain. Numerous well known lockdown sceptic scientists and semi anti vaxers were wheeled out to talk about it and spread the idea via the media and elsewhere.

The same was happening in America and elsewhere. This is well documented in the acclaimed book by Jonathan Howard MD. ‘Tern’ on twitter has summarised some of the messages below:

The people who said covid is mild are the same people who said that it was over in april 2020, who are the same people who said that masks don’t work, who are the same people who said that it’s not airborne, who are the same people who said that it’s just a cold, who are the same people who said that it might kill 40k people in total in america (it’s over 1 million so far), who are the same people who say that it didn’t affect kids, who are the same people who say that it’s good for kids to catch it, who are the same people who say that only vulnerable people are dying, who are the same people who say that it’s good for there to be constant reinfections, who are the same people who said there wouldn’t be reinfections… for them, it always comes back to the same point: they want you infected. That’s why they said about you “we want them infected”.

Many in the UK will recognise this. Media outlets, and particularly the BBC which has been a thorough disgrace in terms of spreading misinformation, have tended to trot out the same people to talk about entirely different ares of medicine all designed to impart the same set of messages captured in the above paragraph.

More generally, the media are continuing to deliberately airbrush Covid out of their reporting and analysis of news items such as record levels of absence from school where Covid is a contributory factor, if not the central causal factor. This is an everyday occurrence. An example from the last 24 hours is that Sky News reported the alarming rise in early deaths from heart disease. The state of the NHS and rise in deprivation are probably part of the explanation for this, and this was acknowledged in the reporting, but what they completely failed to mention, as usual, is the very strong evidence from the British Heart Foundation and many other sources is that Covid infections can damage the cardio vascular system and increase the likelihood of death considerably.

In the meantime the government has said very little to correct the misinformation being banded about, not that anyone would believe them if they they came out and said something evidence based and sensible. The official opposition is little better. Indeed, the only ray of sunshine that seems to get it is Daisy Cooper of the LibDems, though how far this has percolated down to the rest of her party I don’t know. It is also unforgivable that the government Chief Medical Officer remains silent.

Another related factor identified in a recent excellent article by Hayley Gleeson in relation to Australia is that in sharp contrast to the AIDS/HIV epidemic there is no overall public health strategy for dealing with the next stage of Covid. Covid has become politicised and people are sometimes struggling to make sense of it all.

In sum, the public is being exposed to a barrage of misinformation about Covid, including from many medics, which means that people often fail to recognise the continuing very real threats that it poses.

However, this on its own cannot entirely explain why quite a high proportion of people are in complete denial and sometimes display selfish behaviours and are antagonistic to the clinically vulnerable, long covid sufferers and the disabled. The rest of this blog covers possible explanations spanning the economic, social, health, and psychological spheres.

Explanations

The economic argument is that in the UK the pandemic, brexit, government policy choices, stark increases in economic inequalities and other factors have led to a very significant economic squeeze on people’s finances, coupled with significant inflation and increased pressures of work. The argument goes that when people are struggling to keep their heads above water, sometimes going under, they are far less likely to be interested in their long term health or care about other people, and are generally more likely to be operating ‘on a short fuse’.

And people who have to go to work in places where there are no mitigations, don’t have enough money to shop on-line, live in poor areas with poor education and health provision, do not have a strong command of English or the skills to challenge for mitigations are in a far far worse position.

This is not true of everyone of course. The relatively comfortable members of the baby boomers generation, now in their 70’s and 60’s, may also be demonstrating a behaviour shift where they are becoming less tolerant of the needs of others. In fact some people would go as far as suggesting the main problem is in people of these age and social groups and that they are often the ones who are antagonistic to people in their age group who want to keep safe. Again , we have no reliable empirical evidence, but some have suggested that it may reflect an attitude that they have managed to live through a pandemic and are still alive and well and they don’t really give a damm about others.

The economic argument cannot, however, explain everything. The social explanation is equally important.

People tend to be social animals. They like to mix with others in person, go out to crowded places etc. Indeed, the status and sense of worth of many people comes from interacting with and gaining approval from other people.

The pandemic interrupted all of this. People could not go out and many felt rather worthless and stressed. This may have led to a deep fear of ever having to go back to those times, despite the fact of course, that reckless behaviour is more likely to result in restrictions in future.

Fortunately both I am my husband are different. We are independent minded, analytical, love writing and learning, normally detest parties with strangers etc. And my ‘sense of being’ is no where near as dependent on the views of others as it is for some other people.

This is not to say the pandemic has not caused disruptions to our lives – it has, but we have learnt to adapt and cope. But, I recognise that the pandemic and recent economic and social policies have served to widen inequalities across all society and we have not been ‘in it together.

However, the economic and social arguments cannot entirely explain why people find it necessary to turn on others and mock them in various ways.

The health explanation is multifaceted. It is important to remember that many people who have had Covid are still ill, but many people are in denial that they are ill and even less likely to acknowledge that it is anything to do with Covid. We have seen in other posts on this website that Covid impacts on the brain and cognitive functioning in particular – see my post on the tragedy of Long Covid. This could be driving some of the remarkable aggression that we are witnessing. It is certainly a potential explanation for why people seem to be less tolerant of others who are ill, disabled or clinically vulnerable.

However, the most common health related explanation people reach for is the psychological and there has certainly been far more written about this, including new evidence on the links between infection with Covid-19 and mental health disorders.

Cognitive dissonance is often used to explain the inconsistencies in people’s attitudes and behaviours in relation to the threat of climate change, but is also deployed by clinical psychologists to explain a range of everyday situations. It has been defined as follows:

Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort that results from holding two conflicting beliefs, values, or attitudes. People tend to seek consistency in their attitudes and perceptions, so this conflict causes unpleasant feelings of unease or discomfort.

The inconsistency between what people believe and how they behave motivates them to engage in actions that will help minimize feelings of discomfort. People attempt to relieve this tension in different ways, such as by rejecting, explaining away, or avoiding new information.

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-cognitive-dissonance-2795012

Adapting this theory to the current situation regarding Covid, some clinical health psychologists (insert ref) argue that people are using psychological defence mechanisms to downplay the continuing risk of COVID because it provides artificial relief from anxiety. Common behaviours here include saying: “During COVID”,“The pandemic is over”, “Covid is mild”.

This can in turn drive antagonistic attitudes and behaviours to those who continue to take care, because it reduces the bullies own sense of anxiety. Examples here include: “Stop living in fear.” (the attacker is living in fear), “You can take your mask off.” (they are insecure about being unmasked themselves), “You can’t live in fear forever.”

Psychologists say that some people express artificial positive feelings when they are actually experiencing anxiety. eg. “It’s good I got my infection out of the way before the holidays”, “I had Covid but it was mild”, Herd immunity (infections are good for you), “It’s okay because I was recently vaccinated”.

Another mechanism identified by psychologists is termed as artificially reducing Covid anxiety through a weak justification.Examples here include: “I didn’t mask but I used nasal spray”, “I don’t need to mask because I was recently vaccinated”, “It’s not Covid because I don’t have a sore throat”, “It’s not Covid because I took a rapid test 3 days ago.”

Then there is what has been dubbed as intellectualisation or using cognitive arguments to artificallt circumvent Covid anxiety. Examples here might include: Schools refusing air filters or CO2 monitors because it “could make children anxious”, Schools not rapid testing this surge because it “could make children anxious”, Service workers told not to mask because it could make clients uncomfortable etc.

I am not entirely sure sure about some of this and find it difficult to believe that people some of the people I and others encounter are actually anxious about Covid, but the psychological domain is certainly an important part of the equation.

Concluding Comments

In sum, whatever the key drivers are of the behaviours and attitudes we are witnessing, it is bewildering and often upsetting to people who are having to navigate indifference and aggression on regular basis. It is important to try to get to the bottom of the drivers for this reason alone.

But there is another reason why it is important. The fact is that Covid-19 is, at least in part, solvable, with the right policies and commitments. However, this would require clear and focused leadership to drive through investment in, for example, better vaccines and treatments, better health facilities, clean air, better data and better public health measures particularly when infection rates are high. This would require buy in from most of the population. Admittedly there is not much optimism about this in the UK at present, but it is important to remember that in order to ever achieve change we need to better understand where different segments of the population are in terms of their understanding and key drivers of behaviour.

Leave a comment