Last week was the start of what proved to be the most high profile week of public hearings of the inquiry so far. Several high profile figures appeared including Dominic Cummings. In this blog I briefly discuss the extraordinary nature of the hearings before moving on to discuss two key issues: 1. the lack of consideration of real world impacts and 2. the role of scientific evidence.

Many have found the hearings harrowing as the overall picture of lack of preparedness, dithering on the part of the then Prime Minister, Boris Johnson and others, general confusion about roles, including the muddying around the respective roles of special advisors and civil servants, rudeness and bickering at this time when we needed a strong stable sensible government machine, were laid out in full colour for all to see. What has stuck in the gullet of many people, more than anything else to emerge, is that it is claimed that Boris Johnson told senior advisers that the Covid virus was: ‘just nature’s way of dealing with old people’.

Moreover, and perhaps equally appalling, is the failure to learn from the mistakes made during the early months of the pandemic. Essentially the government blundered on to make the similar mistakes, dither, and even fuel the virus through programmes such as ‘Eat out to Help Out’. The result was that the UK endured even lengthier lockdowns in the period November – March 2020/21 than had been the case during spring 2020 and even more people died of Covid as discussed in a recent article by Christina Pagel, published in the New Statesman.

I am not going to dwell on this complete system failure underpinned by lack of any strategic plan, nor the fact that key people were simply not performing their jobs, in particular Martin Reynolds PPS to the PM (a very senior position – not a junior paper shuffler as he tried to imply), in not actively alerting the PM to the emerging crisis. This is all documented by others, in particular Martin Kettle in the Guardian on the complete system failure that is evident from the hearings, and Andrew Rawnsley on the shortcomings of the then PM.

I will comment briefly on two key related issues; firstly, the apparent lack of consideration of the impacts of decisions on real people; and secondly, the role of scientific advice during this crucial period of the pandemic.

Real World Impacts of Decisions

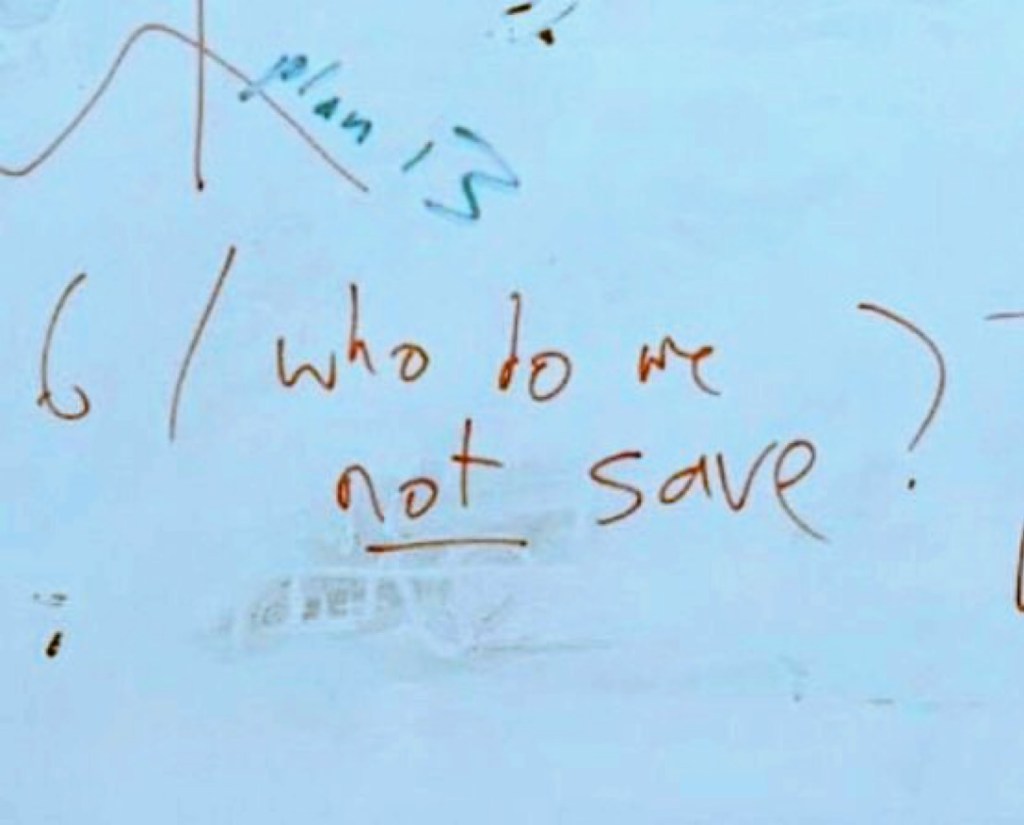

It became obvious throughout the hearings, and particularly from the evidence presented by Helen MacNamara, then Deputy Cabinet Secretary, that most of the politicians and senior civil servants involved gave little thought to how the momentous decisions they were making across the board and on the hoof would impact on real people and how to mitigate the impacts of measures to combat the spread of the virus in real world terms.

There is nothing new in any of this lack of thinking, the only thing that is new is that the sheer scale of the pandemic and the existence of the inquiry which has exposed it.

The fact is that neither our politicians, and particularly the cohort of politicians that have been in power in recent years, nor their senior civil servants have experience of real life as experienced by the vast majority of the population. It is not surprising therefore that decision making across a range of socio, economic and health issues has been exposed as flawed.

The top of the civil service is dominated by people who come from affluent backgrounds and have been to private school. This is because these people are more likely to be appointed at civil service entry level, but as demonstrated by the SMC (Social Mobility Commission) and others, they are more likely to be promoted into high level jobs throughout their careers. Tackling this problem is far from easy but I believe a great deal of effort needs to be put into ensuring recruitment and promotion procedures are not inherently biased towards people with strong oral communication skills and so called ‘softer skills’ often gained through a private school education.

Another other key factor is the overall dominance of economists and economic thinking across the civil service, albeit with a greater concentration in some economic departments such as the Treasury, and the Department of Transport. This is in contrast to other departments with a clear social remit – the Department for Housing and Local Government, for example, where a wider range of real world impacts of policies on real people do tend to be taken into account. These departments also tend to have a relatively strong social research presence vis a vis economists.

The fact that most staff working in number 10 are drawn from the Treasury or ‘economic’ departments probably goes a long way to explaining why in 2020 very few people in number 10 stopped to automatically think – how is this going to impact on real people in practical terms?

Tackling this is not easy because economics is so dominant. I have direct experience of working as Head of Social Research and Evaluation in an economic department – the Department for Transport – between 2001 and 2010. I and many others, including some ministers, did, over the years tried to change the focus so that a wider range of objectives are taken into account when considering transport policy and scheme options. But the strong dominance of economics and the closeness of big spending departments to the Treasury is a key barrier that is difficult to crack.

The Role of Scientific Advice

The Inquiry has thrown up some very pertinent questions about the role of scientific evidence, particularly during the early part of the pandemic and how it came to be ignored to some degree. A recent article in the Guardian by Devi Sridhar sets out the issues very well.

Chris Whitty and Patrick Vallance are often accused of appearing to concur with the policies being announced by politicians despite, as is apparent from Valance’s as yet unpublished diaries, having serious private reservations about what was being said. This is a problem that will be familiar to most people who have ever worked as an analyst in government, but never before have any scientists or analysts been exposed in the way that Whitty and Valance have been.

The key advantage of having in-house scientists, researchers and analysts is that it is far more likely that science and research evidence will be brought to the table at the right time when policy options are being considered. This is not automatic, for example if the in house researchers are not senior enough in the civil service hierarchy, though from personal experience it is definitely the case that in house researchers will be able to influence far more effectively than most external researchers. This is because politicians and senior civil servants know that internal analysts can tailor their advice to what is feasible and that they cannot speak publicly about the discussions that take place within government. This is of course also the key downside of having scientists and researchers based inside Whitehall Departments. They are not fully independent and this is the criticism that has been levelled at Whitty, Valance, the SAGE committee and others.

None of this is easy and without problems and issues. What happened during the early stages of the pandemic is interesting. The SAGE (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies) committee did contain a number of independent experts but also included Patrick Vallance, Chris Whitty, and Jonathan Van Tam. More controversially and in contrast to how SAGE normally operates in an emergency, it also included several political advisors from inside number 10, including Dominic Cummings and Ben Wallace. It was not therefore not truly independent. The committee was also heavily criticised because it did not operate in a transparent way, particularly during the early stages of the pandemic. Even the membership was kept secret along with the research papers and minutes.

In response to how SAGE was operating, the former government chief scientist, Sir David King, set up a new completely independent committee, Independent Sage, that met in public via zoom and in sharp contrast to SAGE was completely transparent. Indie Sage has, in my assessment, been a fantastic success and should be a model to be followed in all future emergencies. As is evident from the Indie Sage website the range of papers, briefings and media interviews have provided an accessible resource for anyone interested in the pandemic.

Not surprisingly most people in the government and the right wing media do not like Indie Sage. In particular the committee is often wrongly portrayed as being pro lockdown, whereas in fact, they have been key advocates of measures such as better ventilation in schools and hospitals, good quality masks, and other measures designed to reduce the need for lockdown.

Earlier this year it became apparent that even Patrick Vallance was also against Indie Sage and that he was concerned that calling the group “Independent Sage” ‘risked undermining Britain’s pandemic response and muddying the waters around crucial public health messages’. I strongly disagree. Indie Sage has provided an invaluable transparent resource for many families as we navigate through the pandemic. SAGE as constituted and operated could not have helped us in this way. As noted by Stephen Griffin co-chair of Indie Sage, that the group was established because of the lack of transparency of Sage itself and … ‘certain critics confuse policy with politics, yet to offer scientifically informed statements on subjects such as supported isolation, or countering transmission, for example, in schools ought not to be controversial.’

Leave a comment