The Pandemic has had a profound impact on many people, not least from the bereavement of family members, anxiety about health, isolation and loneliness. It is understandable that people want to get back to ‘normal’, though it is very unclear what this means. We have very little reliable information on public attitudes to the UK’s current ‘let it rip’ approach to Covid.

In many ways the UK approach is at one end of the spectrum in terms of the lack of interventions to control the spread of infection. This includes a lack of testing, the failure to vaccinate large sections of the population, the dismantling of most data and information systems, and little if no information provision targeted at the public, public sector organisations and businesses.

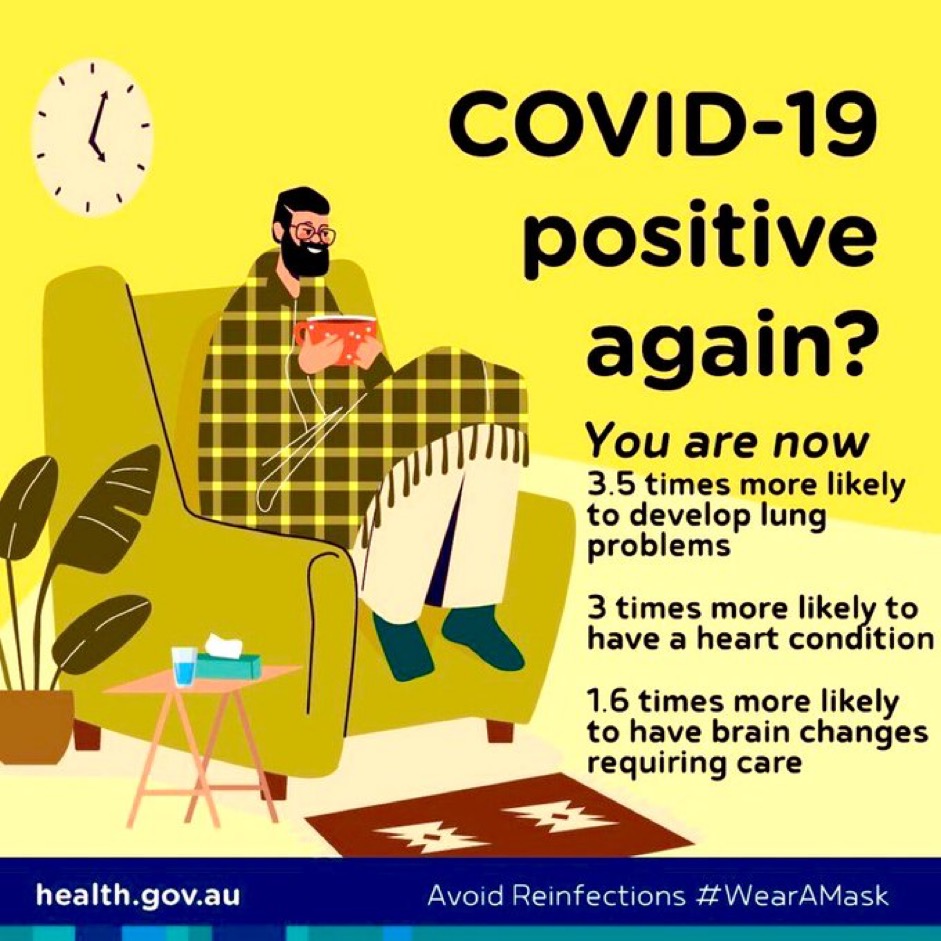

In sharp contrast to the situation in many other countries there seems to be a normalisation in the minds of politicians at least, of the idea of everyone repeatedly catching a virus that doubles or sometimes trebles your chance of diabetes, stroke, heart attack, autoimmune disorder, and various symptoms known as ‘long Covid’ more each time you catch it. The fact that this massively increases the number of people unable to work, reduces life expectancy by several years, damages all sectors of the economy, and continues to bring the NHS to its knees seems not to have registered with the government nor the main opposition. Read the poster below from Australia and reflect on the differences from the UK approach. Also see an article from the US – What doctors wish patients knew about Covid-19 reinfection.

Unfortunately large parts of the media including the BBC, are inclined to subscribe to the view that it is isn’t a problem anymore as well illustrated by a highly misleading piece on the BBC website on 15 October 2023 which I and many others have complained to the BBC about. These sources also tend to bend over backwards to avoid mentioning Covid at all, including when it should be mentioned as a driver of many of the issues they cover, including, for example, high school absences, NHS waiting lists, high excess death rates, staff shortages and closure of hospitality venues.

The approach mirrors that taken in the film ‘Don’t Look Up‘ in which the media ignore or trivialise a scientists discovery that a huge comet that will hit the earth in six months time.

Many people, including myself, are shocked at some newspapers, for example, the Guardian‘s tendency to subscribe to this mindset in their day to day reporting, even though they have some journalists who clearly think otherwise, including George Monbiot and Frances Ryan. This includes an excellent article from George Monbiot which appeared on 16 October and proved to be a great pick me up for many of us recovering from the previous day’s grappling with the BBC complaints website!

But this alternative analysis tends to be reported on-line or in ‘Opinion pieces’ rather than mainstream reporting. Overall, I find that the Independent is a far better source of information on Covid.

The myth that Covid is no longer a serious problem for the UK which underpins the ‘let it rip’ approach does of course pose particular problems for people suffering from long Covid who dare not risk repeat infections, and for the several million who are either clinically vulnerable themselves or live with someone vulnerable.

For many households including on occasions, my own, it often appears that the rest of the country is somehow hostile to us as evidenced by hostility to things like wearing masks, carrying filters, social distancing, requesting that windows be opened, meetings be held outside and non participation in events that would be dangerous for us. These behaviours and how to diffuse them are discussed further in the concluding section of my blog on ‘Avoiding Covid’.

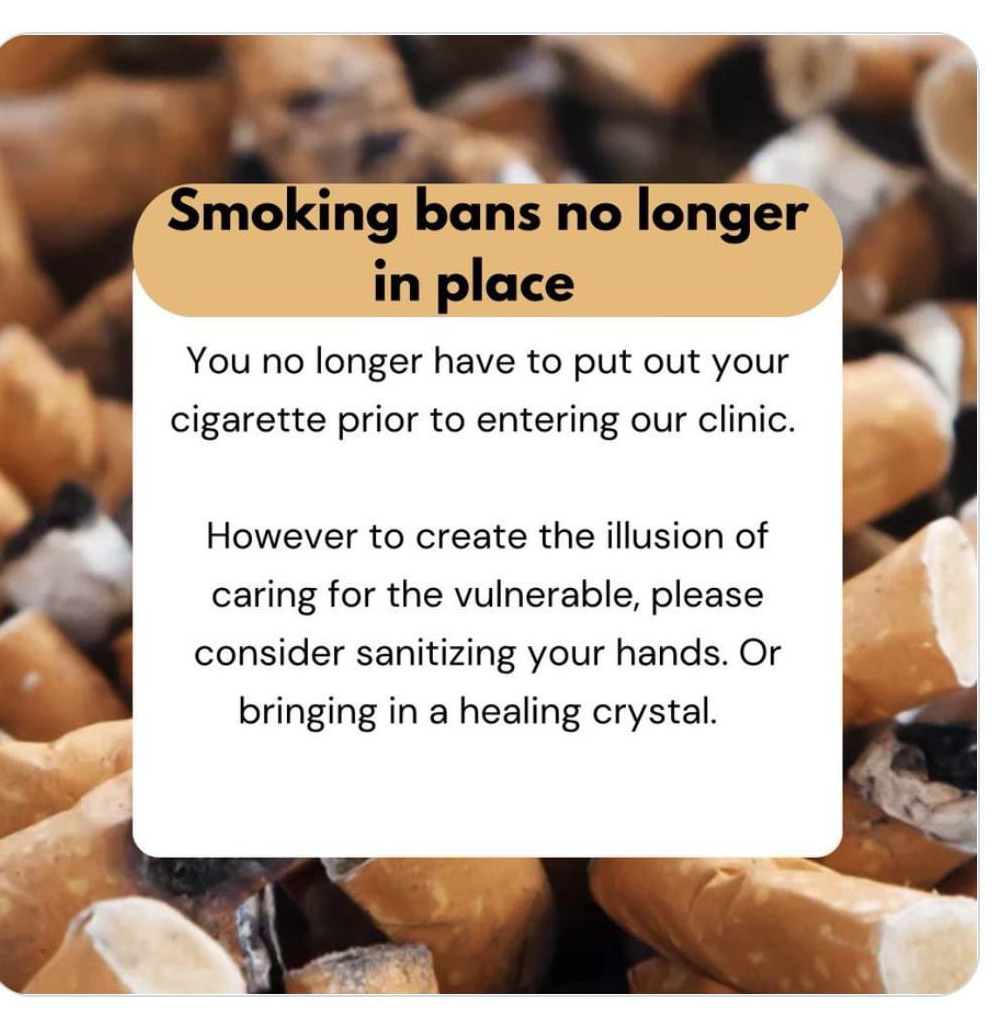

Even large parts of the NHS are sometimes regarded as a problem for failing to follow the science on how to protect patients. Indeed, the spoof poster below resonates with many clinically vulnerable people.

But what is the truth about people’s behaviour and attitudes?

What is clear is that we know very little about what the population as a whole think about the government handling of Covid or the risks to their health.

It is probably the case that some people are aware of the long term damage that Covid can do but do not want to engage with this, because they perceive that it is unsolvable, they can’t see it, and want to carry on as they are because they don’t think it will impact on them or their family and are too trusting of their gut feeling or what other people that they want to fit in with say.

Other people are probably completely oblivious to the long term damage that Covid can do and are genuinely baffled when challenged about this, sometimes preferring to shoot the messenger.

Other people just want to forget the collective trauma they experienced at the height of the pandemic and are not really interested that some people are still in it.

This lack of information on what the public think is responsible to some degree for the strong view in the minds of many vulnerable people that the rest of the country is hostile towards them.

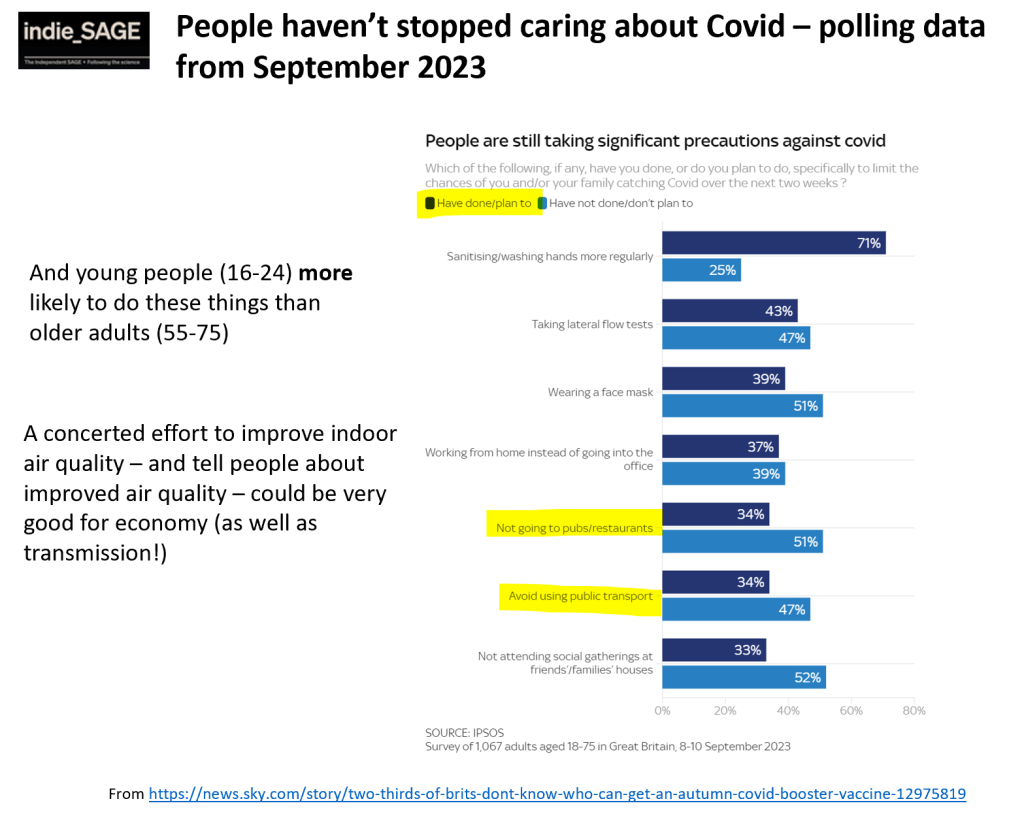

Even though data is scarce, there is some evidence from opinions polls from IPSOS MORI and others.

A recent poll by IPSOS MORI found that a significant minority of people are still taking precautions to avoid catching Covid (see chart) and that young people are more likely to be taking precautions than older people.

There are problems with the patterns of responses of course, mainly that people seem to think that washing their hands will prevent them getting Covid, but given the dire government and NHS messaging here it is perhaps not surprising.

I like many vulnerable people/families felt surprised and relieved to see these poll results. I suspect that the main explanation for this is that people notice hostility whereas they don’t necessarily register the people who put a mask on when around them, or display other sensible behaviours and accommodate their needs.

Professor Christina Pagel draws out three key points from these results.

Firstly, that real-time data on Covid remains important to enable individuals to decide on when to take protective measures. (This is very true. As discussed in several of my blogs on this site, the lack of data on prevalence poses real problems for clinically vulnerable people and their households).

Secondly, it shows that it’s not the case that everyone has moved on from Covid and we should just ignore it. In this sense it is completely at odds with current government and UKHSA policy.

Thirdly, that it shows that if we could support safer indoor spaces (primarily through ventilation and air purification) we could not only reduce transmission but also support the economy by enabling more people to feel comfortable in restaurants, pubs, theatres etc. (I know a number of households, not all of them clinically vulnerable, that can relate to this and wish we lived in countries such as Belgium, that do take Covid seriously.)

Concluding Comments

This analysis highlights the need for more evidence on people’s attitudes, behaviours and perceptions. Without a proper evidence base on where people actually are it is impossible to assess the scale of the economic and social damage being done by the governments stance on Covid and the more general lack of trust. Better evidence could be used to inform future communications about Covid in a targeted way.

Leave a comment