The Covid Inquiry commenced its public hearings on Module 1 – Resilience and Preparedness in June 2023. Inquiry hearings will resume with Module 2 on ‘Decision Making and Governance’ on 3 October.

The hearings are chaired by the head of the inquiry, Heather Hallett, an experienced lawyer and highly regarded politically astute operator. Certainly the impression so far is that she has not been intimidated by high profile witnesses bodes well given that the Autumn module 2 hearings covering decision making and governance in the period from the start of the pandemic will include contributions from Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings. These are almost guaranteed to be lively and controversial.

It is very disappointing that none of the groups representing Clinically Vulnerable Families have not been included as core participants in these first two modules. The Clinically Vulnerable Families group are included in Module 3 on the impact of the Covid pandemic on healthcare systems and Module 4 on vaccines and therapeutics thanks to the hard work of a number of people, including Lara Wong and Cathy Finnis, but the omission from module 2 is particularly serious.

Many of the clinically vulnerable have been either shielding formally because we were told to do so by the government, or shielding informally in the light of our own assessment of the evidence and advice received.

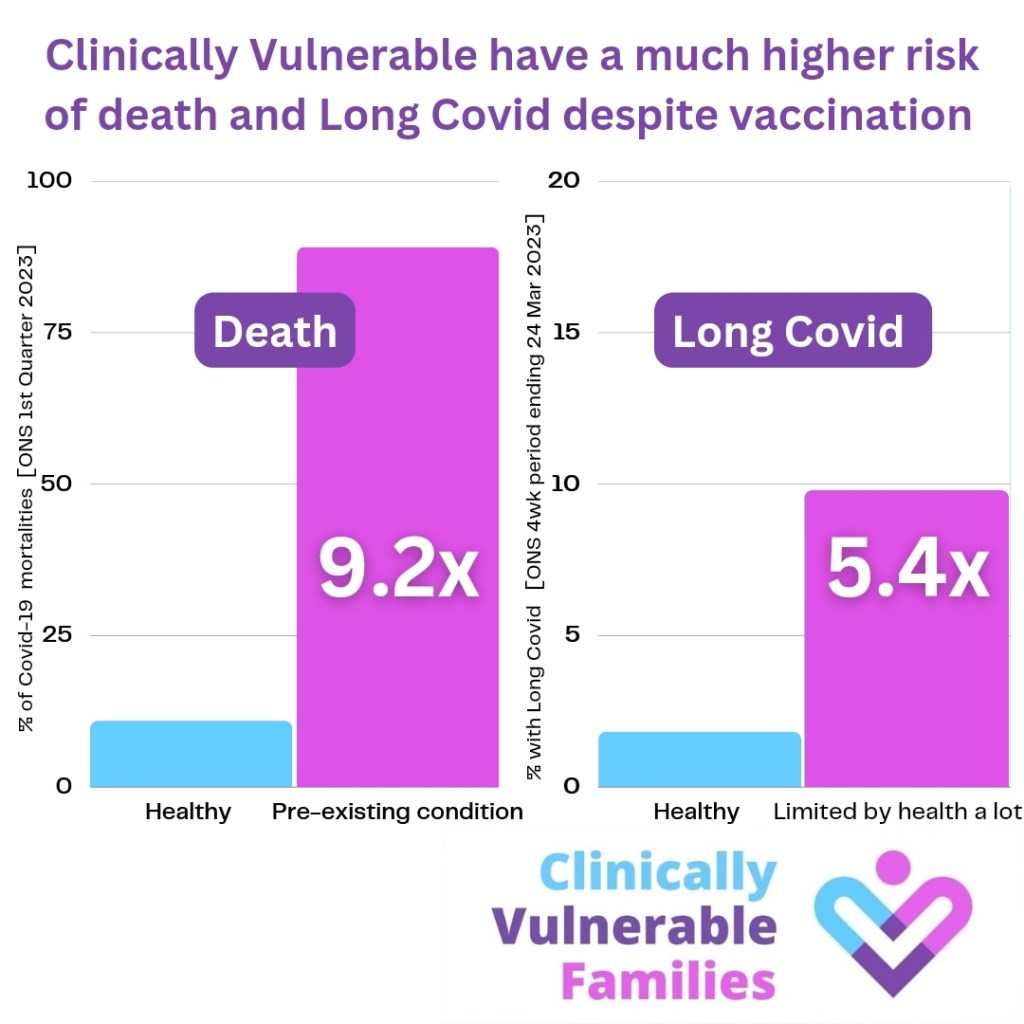

Clinically vulnerable people have a much greater risk of death and long covid despite vaccination as illustrated in the following chart.

We, (including clinically vulnerable people themselves and their household members such as myself) have therefore been more impacted on by the pandemic than most people and the deliberations of module 2 on decision making are directly relevant to us, we have a real contribution to make. Households like mine feel we have been forgotten as the rest of the country has moved on and the exclusion from this stage of the inquiry is a further blow. Nevertheless, it is hoped that the position of and impact of measures on the clinically vulnerable will be taken into account despite our absence from the list of core participants.

Module 1 Reflections

It is worth reflecting on what we have learnt from module 1 on resilience and preparedness as this provides some clues about where the inquiry is heading.

What follows represents my personal reflections on the hearings I have watched or read about. It is not meant to be a comprehensive account.

The strongest point to emerge from this part of the inquiry is just how catastrophically unprepared the UK was for a Covid pandemic.

There is little doubt that two key underlying reasons for this unpreparedness were the chaos surrounding Brexit and the scale of austerity since 2010. This does not mean that other factors were not important, not least the culture and ‘groupthink’ that operates in Whitehall and Westminister, but it was Brexit and austerity that made this a uniquely unsuitable point in our history for a pandemic to strike.

Chaos

The reason why I say Brexit was one of the 2 root causes is the sheer amount of time consumed by ‘planning’ for the UK’s departure from the EU , the controversy surrounding this, and churn in ministers and officials in the period immediately prior to the pandemic (and after it started though this is more relevant to module 2). It is difficult to see how anyone could have taken planning for a pandemic seriously against this backdrop of chaos.

The Government did undertake a pandemic planning exercise Cygnus in 2016 focusing on flu. The findings of Cygnus were challenging and concluded that the UK’s preparedness was not sufficient to cope with the demands of a severe pandemic.

Cygnus made 22 key recommendations but when Covid hit only 8 had been fully implemented. This no doubt reflects the sheer amount of churn and distractions during this period. At the time Covid hit large parts of the civil service, including 70 staff from the Department of Health and Social Care had been redeployed to operation Yellowhammer to prepare the UK for the fallout from a potential no deal Brexit. Pandemic planning was effectively de-prioritised. When Emma Reed, DHSC head of emergency preparedness was questioned by the inquiry about why no one pointed out that they could not afford to stop planning for a pandemic her response was that ‘no deal’ was real and present and a credible threat while a pandemic was ‘a risk of a threat’.

Despite taking place in 2016 the report of Cygnus was not published until October 2020 after pressure from the media and a partial leak to The Guardian.

A key theme running through several sessions of Module 1 is that the work that was done to prepare for a pandemic was geared towards the wrong type of pandemic – a flu pandemic not a Covid -19 type pandemic. Former Health Secretary Matt Hancock made a great thing of this during his evidence, arguing that implementing Cygnus would not have helped very much because it was not about how to control the spread of a disease such as Covid.

This view is disputed by others. Whilst it is true that Cygnus did not address the issue of how to try to stop a virus in its track with measures such as lockdown, and did not address how we might deal with a virus that was sometimes asymptomatic. In other respects some of the recommendations were highly relevant – e.g. the importance of paying attention to social care and stocking up on PPE.

Moreover, another inquiry carried out in 2016, codenamed ‘Alice’ did model the highly relevant outbreak of coronavirus SARs outbreak in which 773 people died in the Far East in 2003-04. This inquiry directly addressed issues such as testing and quarantining of people. However, previous Ministers, including Jeremy Hunt in his evidence to the inquiry, claimed they were never briefed about it and as reported in The Guardian the findings were kept secret despite the potential relevance to informing the response to the pandemic.

Moreover in her evidence Dame Sally Davies, the government Chief Medical Officer 2010 – 2019 said she had visited Hong Kong to learn about Sars Covid 1 and said she had tried to challenge the ‘groupthink’ within government by proposing a SarsCovid review. However, she said she was told ‘oh no it won’t come here’.

Austerity

The Financial Crash of 2008 and the election of a Tory led coalition government in 2010 led to cut backs across the public sector that in a range of ways impacted on the UK’s preparedness for a pandemic.

It is often claimed that the NHS was protected from the worst of the cuts. To some extent this is true, but spending was still cut in real terms over the austerity years despite the working assumption of most health analysts that spending needed to be increased by 5% p.a. in real terms given the ageing population, increasing inequalities and the scale of demand for new drugs and treatments.

In her evidence, former Chief Medical Officer Dame Sally Davies said that compared with similar countries the UK was bottom of the table in terms of the numbers of doctors, nurses, beds, intensive care units, respirators and ventilators. And the BMA in their evidence said that the state of the system had been brutally exposed by the Covid pandemic.

However, the architects of austerity, David Cameron and George Osbourne do not subscribe to this view. Their analysis as outlined by former Chancellor George Osborne in his evidence to the inquiry is that a health system is only as strong as your economy, and that cutting the deficit had a positive impact on the UK’s ability to respond to Covid. Both men did however, accept that they could have done more to prepare the country for extreme risks such as a Covid pandemic.

During the period from 2010 a stagnant NHS focused on dealing with ill people as opposed to building a public health system focused on prevention. Whilst the NHS was protected in relative terms, other services that impacted on public health, including public transport, housing, social care, children and youth services, education, including adult education, faced savage cuts.

Local Authority budgets were cut drastically which meant cut backs to the locally based public health officers who could have made a highly positive contribution to helping t o manage the pandemic through their understanding of their own areas and populations, through contact tracing and other measures.

And it was not simply funding cuts that made the UK uniquely unprepared for a pandemic. The 2012 so called Lansley reforms to the organisation of healthcare fractured the links between public health specialists and the NHS as explained by the BMA in their evidence to the inquiry.

Even the national level body charged with protecting the public from infectious diseases was cut back. In her evidence to the inquiry Dame Jenny Harries said the predecessor organisation to the UK Health and Security Agency which she heads was cutback by 40% in real terms.

In his evidence Sir Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet said that compared to the NHS which treats sick people, what we have not got is an effective public health system that focuses on health promotion and prevention which left us particularly vulnerable to Covid-19.

This is echoed in the evidence from Professor Sir Michael Marmot and Clare Bambra that ‘the UK entered the pandemic with its public services depleted, health improvements stalled, health inequalities increased and health amongst the poorest people in a state of decline’.

Concluding remarks

This has been a brief summary of some of the key hearings and evidence to emerge during module 1. All of the documents and evidence collected during the inquiry can be found on the Covid Inquiry archive.

Module 2 is likely to assume an even higher profile as the inquiry is moving on to consider the period of the pandemic itself. This module will include hearings and evidence on political and administrative governance and decision-making for the UK. It will include the initial response, central government decision making, political and civil service performance, the role of science, as well as the effectiveness of relationships with governments in the devolved administrations and with local and voluntary sectors. Module 2 will also assess decision-making about non-pharmaceutical measures and the factors that contributed to their implementation. Public Hearings kick off on 3 October 2023.

Whilst there is much debate about the issues considered under module 1 about why the UK entered the pandemic period in such bad shape, module 2 is likely to be able the pin down the facts about what happened and why with greater precision, relatively speaking. It is difficult to see how the inquiry can achieve this without direct input from groups representing clinically vulnerable families, but we shall see.

Leave a comment